Tommy Bolin, The Beauty Shines Through

By Paul Rigg

In Tommy Bolin's final live appearance opening for Jeff Beck on 3 December, 1976, he encored with his song Post Toastee, on which he sang: “Well my mind’s been overflowin’, ‘bout some things that don’t seem right […] Seems I got to beware.”

Bolin then posed with Beck backstage for his final photo, which appeared in Rolling Stone, and told a reporter who asked after him: “Don't worry about me; I'm going to be around for a long time.” However, hours later, in a Miami hotel room, Bolin died of an overdose of heroin, alcohol, cocaine and barbiturates.

Bolin was just 25 years old, but he had already established himself as a top musician in bands like James Gang and Deep Purple, as well as producing outstanding and influential solo albums, such as Teaser. He was very much still growing as a progressive rock and jazz guitarist with his distinctive style and was highly respected among his peers. Proof of that includes the 2010 tribute album Mister Bolin's Late Night Revival and 2012’s Tommy Bolin and Friends: Great Gypsy Soul, which featured contributions from musicians of the stature of Peter Frampton (with whom Bolin toured), Myles Kennedy, Derek Trucks and Steve Morse.

What made Bolin into the guitar player he was, and what were the demons that may have contributed to his premature death? Who was the man behind the lurid headlines? Guitars Exchange retraces his life-path and examines his own words in order to try to respond to these questions.

Thomas Richard Bolin came into this world on 1 August, 1951 in the American city of Sioux City, Iowa, from parents of Swedish and Lebanese descent. He showed some early interest in football but an injury led him towards his true passion of music. At around five years old he came across Elvis, Johnny Cash, and Carl Perkins on a TV show called Caravan of Stars, and was fortunate to have parents who encouraged his interest: “When I was five years old my father took us all to see Elvis. I had a leather jacket and combed my hair back. I've always been surrounded by music; that's all I wanted to do. I really wasn't interested in school or anything.”

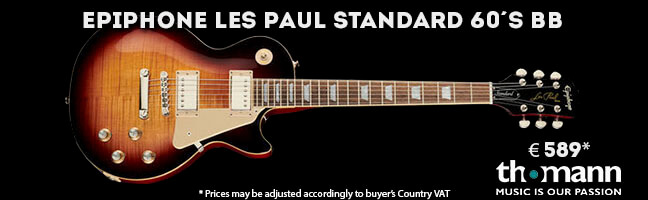

Interestingly Bolin was initially more stimulated by the idea of being a drummer: “I actually started on drums when I was 13, and played them for two years. Then I went to guitar for a year, played keyboards for a year and a half, and went back to guitar. It was just the right instrument. My first guitar was a used Silvertone, the one that had the amplifier in the case. When I bought it, I had a choice between it or this black Les Paul for 75 dollars - I took the Silvertone; that was my first mistake.”

Mistake or not, in 1964 he found himself with a band called Denny and The Triumphs, playing rock and other popular covers, but when the bassist left they changed their name to A Patch of Blue. In 1969 the young band released Patch of Blue Live! based on recordings from two 1967 concerts.

Bolin’s early experience on drums affected his guitar-playing style, as he explained in one interview: “Even now I'll play drums a lot at home, and it will help my wrist action and keep certain things in line, like not speeding up or slowing down. I think the way I play the guitar is very percussive. I play a lot of rhythm chops as though I were playing congas or something.” Bolin was self-taught and although he did have some lessons, he was never too interested in learning scales; preferring instead to learn by jamming and experimenting. As he self-effacingly said later: “You see I can’t read or write music, so I really don’t know what I’m doing. I just go up and fuck around.”

In classic rebellious rock n’ roll style, Bolin was kicked out of school before he was 16 because he refused to cut his hair. Almost comically, the length of his hair then continued to get him into trouble, this time with the police; but the way he tells his story says a lot both about his sense of humour and his humility. “I've got arrested for such weird things,” he explains. “When I left Sioux City, for instance, on my first plane ride -- me and this friend of mine […] were sitting on a plane going to Denver and all of a sudden all these cop cars pulled up.” Apparently their interest in Bolin had been sparked by them being given information that he had some dope in his house. “They put me on probation for the year!,” he explains. “They said I didn't break the law of the state. They said I broke the law of society for having my hair over my ears.”

But that was not the end of it. “Then in Cincinnati, I was doing acid one night […] I was hitch-hiking and at that time my hair was down to here and I had a permanent. I’d just turned 17. The cop said to show him some I.D.; I had eight I.D.s. This was four days after the other bust. We were sleeping under bridges. So I was down at the station for three days. They wouldn't let me make any phone calls. They took me right to the judge. The judge said 30 days in jail [or I could leave if] I had my hair cut. So they cut my hair off. I'd had a permanent, so I looked like a little poodle.”

Bolin moved to Denver where he helped form a band called Zephyr in 1968 and contributed to two of their albums. This was followed by touring with Albert King for a year, from whom he says he learned a lot. “At that time I was playing everything I knew when I took a lead, but King said, ‘Man , just say it all with one note.’ He taught me that it was much harder to be simple than to be complicated during solos. Blues is really good that way.”

Following an aborted attempt to get his own band, Energy, off the ground, Bolin moved to New York in 1973 where Billy Cobham picked him as a session musician on Spectrum, which Jeff Beck has frequently described as being a major influence on his own jazz interests. Around this time Bolin also stepped in for Domenic Troiano, who had replaced Joe Walsh, in the James Gang, and recorded two albums: Bang in 1973 and Miami in 1974, on which he either wrote or co-wrote nearly all the songs.

Deep Purple’s keyboardist Jon Lord had heard Spectrum and called it "an utterly astounding album. There was Tommy Bolin just shredding away like mad. And it was just gorgeous stuff, all improvised, all just off the top of his head." Vocalist David Coverdale also loved Bolin’s contributions and consequently, in 1975, when Ritchie Blackmore left Deep Purple and Bolin was recording his own album, he got a call from the band asking him to come over for a jam. Bolin says that up to that point “I had [only] heard two songs by Purple, ‘Smoke On the Water’ and some other song” – but four hours later he was offered the job.

Deep Purple’s Come Taste the Band, on which Bolin wrote or co-wrote all but two of the tracks, was released in late 1975, and they began a tour of Australia, Japan and the US. However Bolin’s own album Teaser was released during this tour, which meant that the guitarist was unable to promote it in the way he might have liked.

When Deep Purple split up, Bolin saw his opportunity to invest more heavily in his next album, Private Eyes. This latter offering included several rock numbers such as Busting Out For Rosey, Post Toastee and Shake the Devil, but most of it is more jazz-oriented. As Bolin said: “The Purple thing was great for a while, but it started to get a little too tense. I’m still great friends with them, it was more a management problem. They were hassling me with this and that…money wise it got kind of weird me being an American and them being English, so I just quietly removed myself. I’m sick of diving in other people’s pools.”

This latter comment points towards what might have been a cause of his growing dissatisfaction. As Karen Ulibarri-Hughes, his long-time girlfriend, later said: "A very sad stigma that followed Tommy joining these groups was the fact that he was always a replacement. It was very hard for him to be on stage and hear, "Joe Walsh!" or "Where’s Ritchie?" This is what haunted him during the English tour [and he was] booed off the stage. He played terribly, he was just so unhappy. The reception was miserable, so his attitude was miserable."

Bolin himself seemed to confirm this opinion in an interview just two months before his death: “It was difficult following a guy like Ritchie Blackmore. When someone is the focal point of a group like he was, it's very hard to replace them. After a while, it just got to be pointless.”

After leaving Deep Purple, Bolin also seemed to be facing financial difficulties and found himself opening for bands in much smaller venues. “It bothers me when they only give me three feet to play on, and the monitors aren’t exactly what I want. [They give you] 40 minutes, and that’s bullshit with a two group thing - What can you do in 40 minutes? You just start to cook, then you have to get off the stage. You leave the kids hanging while they’re still applauding and the house lights go on. The kids think you’re the one that said ‘Fuck You’.”

So disappointment seemed to be piling upon disappointment and Bolin, like many others, may have sought to deal with this by increasingly relying on drugs. A live album, Last Concert in Japan, was then released against Deep Purple’s wishes as, among other reasons, it featured a below-par performance from Bolin, who had been unable to play properly having fallen asleep on his left arm for eight hours before the concert.

Bolin may have only had four guitar lessons in a life that was cut tragically short, but in that time he created sublime music and gained respect among his peers both for his professional and personal qualities. As Alabama founder and songwriter Jeff Cook says: “what Tommy did was grab the essence of what great guitar players were doing and then mould it to himself.” And as Deep Purple bassist Glenn Hughes adds: “Tommy was the most beautiful person you could hope to meet, his music shone through that, and you could tell.”