Glen Buxton, Rebel Without a Cause

By Paul Rigg

Picture this: it is 1971 and Alice Cooper have four albums behind them but are still looking for that one big spark to really set the house on fire. Guitarist Glen Buxton has already contributed the riff to I'm Eighteen, which has given the band a lot of exposure, but he is now looking for something that will speak to every adolescent: and what better than a theme about school closure? Reportedly inspired by school kids’ mocking chant of 'Na, Na; Na, Na, Na,' he finds the genius riff to which the lead singer adds not just incendiary lyrics, but the fantasy that the entire ‘school’s been blown to pieces.’

Teachers, parents, headteachers, and psychologists all called for it to be banned and a number of radio stations refused to play it. In other words, it was rock n roll gold, and suddenly the group was at its peak. The song hit the Top 10 on the US Billboard chart, and was number one in the UK for three weeks in August 1972. Alice Cooper moved from an oft-derided theatrical act to a supergroup. Sold out concerts all over the world invariably closed with the anthem that everyone loved to sing-a-long to.

"Glen wrote the riff to School's Out; we all sat down and jammed together with that riff. Neal [Smith] worked up his drum part. We knew the riff that Glen had come up with was special," said guest guitarist, Rockin' Reggie Vincent. Cooper agreed that Buxton“created School’s Out […] he created all that stuff. Those riffs would show up on the album, and even great guitar players would say, 'What is that line? It's so weird, but it's catchy’. […] He ended up being one of the great rock guitar players of all time.”

But like so many great rock stars, Buxton’s inner demons consumed him, and he never lived to see his fiftieth birthday. So, what was the source of his pain?

Glen Edward Buxton came into this world on November 10, 1947 in Akron, Ohio, but in his early teens moved with his family to Phoenix, Arizona. Searching for someone to model himself on, he came across James Dean, the glamorous but tragic film star who had a penchant for driving fast cars at night with the headlights turned off. That restless and reckless spirit also inhabited one of his other icons, Elvis Presley, who was helping give birth to a new kind of music. In rock n roll Buxton found a home for his anti-conformist spirit and at the age of 10 asked his parents for a guitar for his next birthday. They agreed as long as he took lessons, and suddenly Buxton found a means with which he could express himself.

Those guitar classes were to hold him in good stead when, at his school, Cortez High, he formed a band called The Earwigs that included schoolmates Dennis Dunaway and Vincent Furnier, who was later to adopt the stage name Alice Cooper. Buxton was the only one who could actually play an instrument but encouraged the others, with Dunaway taking up bass and Furnier grabbing the lead role on the mic. The name of the band was a clear reference to the Fab Four but, as Buxton later explained: “the Beatles were too complicated for us to play, but when the Stones came along with three chords we thought ‘hey, this is a snap!’; and then the Kinks come along with just two chords: Wow, we jumped at that!”

Later Alice Cooper recalled Buxton at that time as “dressing like the biggest juvenile delinquent in the school; [he] smoked cigarettes and fought.”

Dunaway convinced Furnier that they should compete in the school’s annual Talent Show and with Buxton’s help, they started to get their heads around the odd Beatles’s song, as well as some of Buxton’s favourites like Chet Atkins and Les Paul. Among over a dozen bands they won second place, not so much because of their sound quality but because of their charismatic stage presence. This gave them a name in the school and motivated them to practise together every single week.

As they grew, The Earwigs became The Spiders in 1965, then The Nazz in 1967, and finally Alice Cooper in 1968, at around the same time that two of Buxton, Dunaway and Furnier’s schoolmates left, and rhythm guitarist and keyboardist Michael Bruce and drummer Neal Smith joined. The new line up produced more or less an album a year before 1972’s School’s Out catapulted them onto another level.

Billion Dollar Babies the following year was also a chart topper, and the world tour to support it saw the band play in 27 countries, with the highlight being their concert in Brazil in front of 158,000 fans, which earned them a spot in the Guiness Book of Records for the biggest ever indoor concert.

Dunaway describes the day they shot some of the artwork for the album: "The B$B promo pic was an early morning shoot in London, after a night on the town. […] Getting a million dollars in American cash was extremely difficult. It arrived with a couple of Bobbies who had no guns. There was a lot more money than we imagined so we stacked a portion of it in front of us and eventually ended up throwing it around the room for effect. When the photo session was over, we had to wait while all the money was counted. Hours later, the Bobbies said twenty dollars was missing. Nobody fessed up until Glen finally pulled a bill out of his pocket so the Bobbies would allow us to go back to the hotel to sleep. Later, Neal said he saw Glen snatch the bill but everyone knew who took it all along. He didn't need the money, he was just being Glen."

That gives a small snapshot about the fun part of success. Unfortunately, as is so often the case, the higher you climb the harder you fall, and while there are different stories told by each band member, Buxton recalled it like this: “the downside – and Alice has said this too – is that we never took time to enjoy the fruits of our labour, all we did was labour; on the billion dollar babies tour we had one day off in 90 days.” Buxton said that he increasingly felt sickened by the music industry and wanted to kick back for a while and spend time with his family.

Reggie Vincent gives another perspective: “Glen liked drinking, a lot. He drank because he liked the image of himself as a rock star with a bottle in his hand. He sought refuge in the bottle, not really in order to forget... but mainly to destroy himself.”

But what was the source of his pain? We can only speculate but some around Buxton at the time wonder if the pressures of having to maintain, or surpass, the same high level - and the self-doubt about whether he could do it - were contributing factors. As Dunaway puts it: “Glen always rebelled against anybody who told him how to do anything. As things progressed, the band was pressured to do things in a short period of time, and we were expected to create hits. And because of that, the record company became authority, and that’s when Glen kind of dropped out.” However producer Bob Ezrin adds a different angle, which is hard, but seems to go deeper: “Things would come up that were difficult to play, and Glen wasn’t quite up for the task. I think he ran away from situations where he felt embarrassed, and he was becoming more and more embarrassed as time went on.”

Buxton was "not invited" to play on the following album Muscle of Love (1973) – other guitarists stood in for him - but he was given a credit, in order to maintain the band’s image.

The group separated in 1974, with Cooper finding success with Welcome to My Nightmare, and the other members going in different directions.

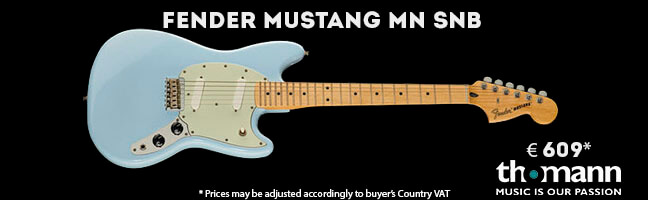

In 1985, Buxton returned to the stage for a few concerts with a band called Virgin, of which there is a poor quality but interesting clip in our video selection from around that time. Here he can be seen playing a Fender Mustang instead of the 1967 Gibson SG custom white that he can be seen with on many of Alice Cooper’s most famous songs.

In 1996 Buxton made an appearance on the album Lunar Musik by Ant-Bee and formed Buxton-Flynn with with his long time friend, Michael Flynn, from Minnesota, but in those years he often led a much quieter life.

In October 1997 most of the Alice Cooper Band came together for a brief reunion at the Hard Rock Cafe in Houston. This was followed by an offer by radio KLOL to do an early morning simulcast, at which Buxton showed his nerves and complained of chest pain; although he refused to go to a local doctor to have it checked out. The reunion nonetheless had been a big success, and tentative plans were being made for much more. Buxton however had contracted pneumonia during the trip, and shortly after he died of complications at a hospital in Iowa, on October 19, 1997.

In the blink of an eye, triumph had turned to tragedy. At Buxton’s funeral, the band and family members watched as his headstone was gradually revealed to show an imposing marble rendition of School's Out’s classic opening notes engraved upon it.

“Glen was a genuine rock and roll rebel," concluded Alice.

RIP Glen Buxton November 10, 1947 – October 19, 1997