Harvey Mandel, the unjustly forgotten snake

By Sergio Ariza

The name of our protagonist may not ring a bell at first, but we're going to give you a few clues about the enormous guitarist we're talking about: he came out of the Chicago blues scene where he got to play with all the greats, from Howlin' Wolf to Buddy Guy, he recorded one of the foundational blues rock albums with Charlie Musselwhite, he took the stage at Woodstock with Canned Heat, he was one of the guitarists chosen by John Mayall (who has had a special eye for it since the days of Clapton and Peter Green), came close to becoming a Rolling Stone and was one of the first rock musicians to use the tapping technique, with several sources claiming he was the main inspiration for Eddie Van Halen to take it into the stratosphere. Ladies and gentlemen, we present you with, the snake, Mr Harvey Mandel.

Although he was born in Detroit on 11 March 1945, Mandel has always considered himself a Chicagoan, as his family moved to the windy city when he was still very young. He could not have been luckier, Chicago in the 50s was the Mecca of electric blues and for those who were fortunate enough to live there, seeing giants such as Muddy Waters, Howlin' Wolf, Elmore James and Buddy Guy live was the most common thing in the world. This was the case of Mandel who, although he started out playing the bongos, decided to switch to the six strings at the age of 16 when a guitarist friend taught him his first chord. His father bought him an acoustic Harmony for $16 and within weeks Mandel was fiddling with a radio to turn it into a primitive speaker, again his father, amazed at his ability, took him to Sears and bought him an electric guitar and amplifier, both Silvertones. He would never again go a day in his life without playing a guitar.

After starting out, Mandel began hanging out with other white kids fascinated by the blues, people like Barry Goldberg and Charlie Musselwhite, and soon, thanks to Sammy Fender, he was learning the ropes at the Twist City jams - and before he was 21 and able to enter or drink in those places, he was on stage with the greatest musicians in blues history. Maybe there is no better school than that for someone who wants to play the blues, while in England Clapton, Beck or Green had to be satisfied with just listening to the records, Mandel and Mike Bloomfield had the luxury of being on stage with all of them, Waters, Wolf, Guy.... Mandel began to make a name for himself, although he did not have the mythical aura of Bloomfield, the other great white guitarist from Chicago.

When Bloomfield joined Paul Butterfield in the latter's band, blues rock began to open doors across the USA. In Chicago, Mandel had teamed up with Goldberg and Musselwhite and, under the former's leadership, they had released an album in 1966 called Blowing My Mind, with the guitarist already excelling on several tracks with his aggressive approach and accurate licks. Even so, things would get a lot better the following year when the three players would repeat, this time under the leadership of the brilliant harmonica player Musselwhite, and they recorded one of the essential white blues rock albums of the 60s, Stand Back! Here Comes Charley Musselwhite's South Side Band.

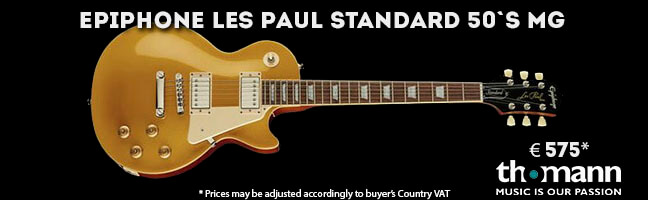

Mandel's work is excellent throughout the album, which includes such superb pieces as Christo Redemptor, Help Me, one of the few sung, or 4 PM, composed by Mandel himself, where his style can be appreciated in all its glory, with an incredible sustained and cutting tone that could be considered a forerunner of Paul Kossoff's, and that, possibly, was with his Gibson ES-335. The record has been equated with the two cornerstones on which the blues rock edifice was built, the first two Paul Butterfield Blues Band albums with Mike Bloomfield and John Mayall's must-have album with Eric Clapton.

Bill Graham, the legendary owner of the Fillmore in San Francisco must have had a similar thought, as he invited Mandel and Musselwhite to present that album on a bill that included Electric Flag, Bloomfield's new band, and Cream, Clapton's new band. Mandel showed up with his little Fender amp and a 12-inch speaker, his Chicago club gear, and found a wall full of Clapton-owned Marshalls. A self-conscious Mandel approached the God of British guitarists and asked if he could borrow them for his performance. God was, that day, merciful.

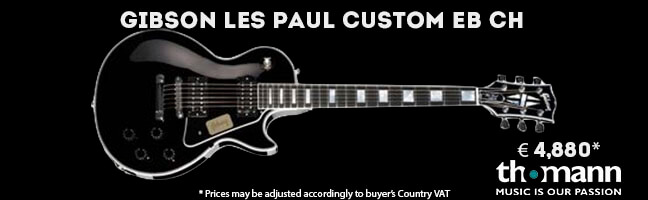

After that gig Musselwhite's band disbanded and Mandel decided to stay in San Francisco and try his luck in the city's nascent scene. Soon he was jamming with Jerry Garcia and Elvin Bishop at the legendary The Matrix. It was there that he was discovered by local DJ and producer Abe Keshishian, who signed him to Philips Records where he would release his first solo album, Cristo Redentor, in 1968. It was an instrumental album in which Mandel flirted with jazz, anticipating the fusion of jazz and rock in the 1970s. The best known song is the title track, the same song he had recorded with Musselwhite but now with his unmistakable tone, possibly on a Les Paul Custom, mixed with luxurious strings and incredible soprano vocals. Also of note is the subjugating, psychedelic Wade In The Water.

The following year, in 1969, he got back together with Goldberg for some jams in which Bloomfield was also involved and which were released under the title Barry Goldberg & Friends. But, without a doubt, the most important thing that happened to him that year was going to the Fillmore East the night Henry Vestine left Canned Heat. Bloomfield was also there and it was he who joined them for the band's first set, but for the second it was Mandel who played with Bob "the Bear" Hite and Alan "Blind Owl" Wilson. They didn't hesitate to hire him, evidently because of his enormous quality, although his nickname, "the snake" (which Goldberg gave him not only because of his prolonged sustain but also because of his unpredictability, the listener was never sure which way he was going), suited them like a glove.

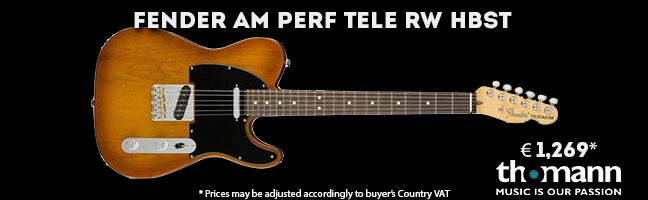

His third concert with them was in front of half a million people at Woodstock, where they were one of the big winners of the three days of "peace, love and music". They opened with the unstoppable Going Up With The Country, with a magnificent solo by him, but it was when they played Fried Hockey Boogie, from their album Boogie With Canned Heat, that it became clear that Mandel was the best guitarist who had ever played with the band. With Janis Joplin and Jefferson Airplane's Grace Slick as exceptional witnesses at the back of the stage, Mandel launched into a scintillating solo, his work on On The Road Again is also magnificent with his black Fender Stratocaster in perfect dialogue with Wilson's Les Paul.

Mandel stayed with the band for a year in which he would record one of their most successful songs, the cover of Wilbert Harrison's Let's Work Together, and one of Canned Heat's best albums, Future Blues, released in 1970, with his excellent work on the six strings on songs like the title track, if you listen to the live performance below, with a Telecaster, My Time Ain't Long, one of the best solos of his career, or So Sad (The World's in a Tangle).

But, just as that album saw the light of day, in August 1970, Mandel and Canned Heat bassist Larry Taylor left the band to join John Mayall's newly reshaped Bluesbreakers, where Mandel would follow in the footsteps of Clapton, Peter Green and Mick Taylor. With Mayall he recorded two albums, USA Union, in 1970, and Back to the Roots, in 1971, an album in which Clapton and Taylor played again with Mayall; by the way, on Accidental Suicide, about Jimi Hendrix, the three of them play together.

He then became part of Pure Food & Drug Act, alongside people like violinist "Sugarcane" Harris and guitarist Randy Resnick, who taught him tapping (although Ritchie Blackmore claimed to have seen Mandel use the technique as early as 1968 on Whiskey A Go-Go). During the same period he recorded Baby Batter in 1971, his fourth solo album and his best, along with his first. His original frenetic fusion of funk, jazz licks and blues-rock is a work to be listened to on repeat and anticipates later albums by people like Jeff Beck and Al Di Meola. The two most outstanding pieces are the title track and the funky El Stinger. In 1973 would come Shangrenade, another instrumental solo album, where he makes extensive use of two-hand tapping on the title track.

But the juiciest part of his career was about to come: in 1975 he received a call from Mick Jagger telling him to go to Munich to record a couple of songs with the Rolling Stones. Mandel, like everyone else, knew that Mick Taylor had jumped ship, so this was nothing more than an audition to become a Rolling Stone. During the days he was there, Mandel recorded two tracks with the band, the beautiful Memory Motel and the funky Hot Stuff. The former is one of my clear choices as a ‘lost’ Stones gem, a marvel in which Jagger and Richards share vocal duties and Mandel shows his class on guitar. Although it is on the second, a clear forerunner of Miss You, that he has the most chance to shine, using a wah wah.

While staying at the hotel one night, Mick Jagger came to his room in his bathrobe and, for a second, he thought that to be a Stone you had to do more than just play the guitar, but the singer had only stopped by to congratulate him on his work. It seems that Jagger wanted him - a quiet guy in the shadows, but with a superb technique like Taylor - but in the end Keith won, because what he wanted was a partner for a night out and he found him, perfectly, in good old Ron Wood.

A nice anecdote is that when Mandel was in really bad shape and had financial problems with his cancer treatment in the middle of the second decade of the 21st century, Richards didn't hesitate to send him one of his guitars to auction off.

Harvey Mandel did not become a Rolling Stone and his name seems unfairly forgotten in the mists of time but, to this day, he continues to play true to his convictions, "There is a distinct difference between being a good musician and playing a good song... It takes years to get to the point where there is nothing physical left to learn, where everything is purely in the mind. There's always the physical part. Usually that's the technique and that's the fine point between a lot of us. I think what helps me is that I have an original style. I don't try to copy the general trend... I don't consider myself a blues guitar player or this or that. I'm a guitar player. In other words, I don't just play guitar, I play music, which means I try to play everything”.