Peter Gabriel, Escaping The Cage

By Sergio Ariza

For Peter Gabriel, genres are totally reductive and meaningless. He believes there is only good or bad music, whether you call it progressive or punk, country or soul, rock or world music, the important thing for him will always be how a song is arrived at and the processes it goes through. Whether the song is by Randy Newman or Youssou N'Dour, one of the artists he made known in the West, the only thing that labels do is put music in a cage, from which Gabriel has always wanted to free it.

His career is an achievement in itself, but he was also one of the first artists in the Anglo-Saxon world who stopped looking at his own navel and saw that there was a whole world of music and probabilities outside the USA and England. Gabriel was one of the leading proponents of what came to be called World Music, and which had as one of its main promoters WOMAD created by Gabriel himself, an event that could have as its motto one of this artist's most famous phrases: "If you know the music of other countries, you cannot be racist".

Born in Chobham, Surrey, on 13 February 1950, Peter Brian Gabriel came from an upper middle-class family, where one of his ancestors had become Mayor of London; while his mother's family was involved in the world of art and music. It was his mother who taught him to play the piano at a tender age, although, like most boys of his generation, he fell in love with rock & roll and American music. One of his first passions was soul and the first instrument he played in a band was the drums. In 1965 he formed The Garden Wall, a trio in which he sang with his friends Tony Banks on keyboards and Chris Stewart on drums.

In December of that year they played with another band that had formed at Charterhouse School, called Anon, which included Anthony Phillips and Mike Rutherford. In January 1967 the latter two invited the members of Garden Wall to record demos with them. The demos reached the ears of another Charterhouse alumnus, Jonathan King, who signed them to Decca. They had a label but no name, so they set about it and, after rejecting the name Gabriel's Angels, they ended up deciding on Genesis.

After a few sparse pastoral folk singles, they recorded their first album, From Genesis to Revelation, in 1969, still without a clear direction, mixing psychedelia and echoes of the early Bee Gees, by which time John Silver had replaced Stewart as the band's drummer. The album sold only 650 copies and the members of Genesis seriously considered going back to their studies and forgetting about pop music.

They didn't and, impulsed by Phillips decided to take up music as their sole profession and began to write and play much more complex and advanced material. To this end they started rehearsing and playing like crazy, and there was a new change on drums: with John Mayhew coming in and Silver leaving. Their numerous live performances were turning them into good musicians and the material was improving. They usually wrote in pairs, on one side was the Garden Wall duo of Gabriel and Banks, and, on the other, the Anon duo of Rutherford and Phillips. The best song of this period, which appeared on their second album, Trespass, called The Knife, was mainly by the former.

Shortly after its release Phillips had a breakdown, exacerbated by stage fright, and left the band, but the other three main members decided to carry on, and replaced Mayhew with Phil Collins on drums. It was a fundamental change that made the band much better musically. As well as being a great drummer, Collins could sing and do backing vocals for Gabriel. Shortly before they started recording their third album, the piece that closed the best line-up the band ever had, Steve Hackett, came in as guitarist. The result was Nursery Cryme, their best work to date.

Even so, it could be said that Genesis began to be a really important band from the next album, Foxtrot, released on October 6th 1972. By then Gabriel had already introduced his sense of theatricality into his live performances and his complex, literary lyrics had made him the band's focal point. The album included the band's first two great classics, the progressive, sci-fi rock of Watcher of the Skies and the extended suite entitled Supper's Ready, which contained an acoustic piece by Gabriel called Willow Farm and a jam by the rest of the band entitled Apocalypse in 9/8.

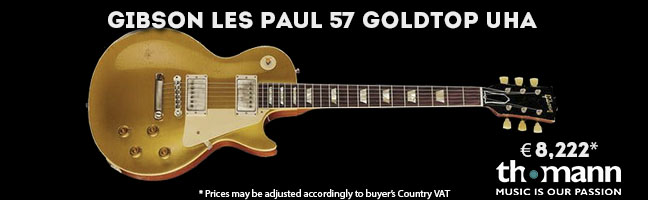

It was the beginning of their golden age, but also the beginning of the separation between the frontman and the rest of the band. Then came their first masterpiece, Selling England by the Pound, with Gabriel's lyrics about the decline of English culture and the rise of American influences, as well as capitalism. Musically, the band went a step further with songs like Firth Of Fifth, in which Hackett entered the Olympus of great guitarists with an incredible solo on his '57 Les Paul, but there were also many more catchy songs like I Know What I Like (In Your Wardrobe), which could have passed for a glam rock single, a genre that was in vogue at the time.

Then came their best album, The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, a work that advanced Gabriel's solo career but also demonstrated the enormous strength of the other musicians in the band: just listen to Rutherford's aggressive bass on the title track or Collins' drums on Fly on a Windshield. The singer managed to consecrate his conceptual story about Rael, a Puerto Rican in jeans and a leather jacket (who anticipated punks), at the expense of the rest of the band who wanted to do an álbum about The Little Prince. But it was 1974 and Gabriel had already seen how ‘the progressive rock ship’ had become an ocean liner of excess, and he didn't want to sink "on that Titanic". The Lamb Lies Down On Broadway is still progressive but full of rage and aggression, which makes it very special, as well as containing some of the band's best songs, such as the title track, In The Cage, The Lamia, Back in NYC, Fly on a Windshield, The Chamber of 32 Doors and, above all, the masterful Carpet Crawlers.

After a string of successful performances came the break-up. Gabriel said he was disillusioned with the music industry and wanted to spend more time with his family, the other members weren’t too upset because it was obvious that the singer was the one who was taking all the spotlight; so two separate careers emerged. Everything Gabriel felt at that time is reflected on the legendary Solsbury Hill, which appears on his first solo album. The album was the first of a series of four self-titled works, in which it can be seen that Gabriel's adventurous spirit is still with him, experimenting with different sounds and musicians, always with the eye of a musician who is looking to innovate in his art and not be overly-focused on the charts.

The list of collaborators on those first albums is very long and of an extraordinary level. We, as guitar lovers, can highlight Steve Hunter, who was in charge of playing the acoustic on Solsbury Hill, with a Martin D-18 or 28, his partner Dick Wagner, who plays the electric on Here Comes The Flood, or the incredible Robert Fripp, from King Crimson, who was in charge of producing Gabriel's second album, as well as playing the guitar on most of his songs. On the third album we find the surprise appearance of the Jam's leader, Paul Weller, who plays on the catchy And Through the Wire. Fripp once again makes his presence felt, although it is the first album on which the man who would become his permanent guitarist appears - accompanying the essential Tony Levin on bass - David Rhodes, in his band.

But perhaps the greatest collaboration of Gabriel’s career was with the great Kate Bush, who can be considered a kindred spirit, always looking for new ways to achieve something totally personal. What's more, the instrument on which Bush would build future masterpieces, such as The Dreaming or Hounds Of Love, the Fairlight CMI synthesizer, she got to know while recording with Gabriel that ‘accidental hymn against war’, Games Without Frontiers. In 1986 the duo recorded their most memorable collaboration, the song Don't Give Up, from the most important album of Gabriel's career, So, which definitively opened the doors to megastardom, with Sledgehammer becoming the most played video in the history of MTV, and songs like In Your Eyes becoming part of the pop culture of the decade thanks to its inclusion in Cameron Crowe's Say Anything, with the mythical scene of John Cusack playing it on his radio-cassette.

But instead of living off the money he had made, Gabriel took advantage of his fame to explore his more humanitarian and political facet with concerts for Amnesty International, or consolidating his recently created World of Music, Arts and Dance festival, better known as WOMAD, with which he wanted to make music from all parts of the planet visible. This was an influence that was already noticeable in his work, such as the on impressive Biko, with which he made this fighter against Apartheid visible.

WOMAD, however, didn't get off to a good start and in 1982, in the first edition, Gabriel almost went bankrupt despite a line-up that included himself, Don Cherry, The Beat, Drummers of Burundi, Echo & The Bunnymen, Imrat Khan, Prince Nico Mbarga, Simple Minds, Suns of Arqa, The Chieftains and Ekome National Dance Company. Luckily his friends from Genesis lent him a hand and that same year Gabriel joined them for an event called Six Of The Best, which Hackett also joined; the proceeds of which saved future editions of WOMAD. This year marks its 40th anniversary and is expected to be a similar success to its 35th, in 2017, which featured among others, Emir Kusturica & The No Smoking Orchestra, Toots and The Maytals, Seun Kuti & Egypt 80 and Roy Ayers, in front of an audience of over 10,000 people.

It remains one of the greatest achievements of a man for whom art was always more important than business and who even declared: "I would love to have a songwriters' event where the Sherman brothers would play their songs for 'Mary Poppins' and 'The Jungle Book' with Trent Reznor and Dr. Dre, and everyone would talk about how they wrote the songs," he reflected. "That's what fascinates me: how you come up with a song and the processes you go through. Everything else is bullshit.”