The blues is flamenco in English

By Alberto D. Prieto

Beginnings, tremors, ecstasies,

crazy solos without end, portents of tragedy, respect between voice and

instruments, shouts, and even the structure of what is sung. When arthritis should be

playing its role, the one who plays is

Walter Trout.

On Wednesday, November 7,

in the Mon room in Madrid, an

old dude from New Jersey climbed

up on to the stage, with 67 years behind him, trembling hands, swollen gut,

sparse hair and a lost look. Like those guys who you feel for because they

approach you with a stale smell and a lot of pain to offer conversation, in

that strange place between total calm and losing it entirely, every Sunday of a

summer dying while you sip your beer. You listen - what else to do on that

first day? - but then, how interesting it becomes. Not exactly in what he says,

but because within what he says you

know there lies a truth. He talks calmly

about tragedies, he describes them starkly, but he does not complain; it is

what it is, boy, these scars, these deep wrinkles, and how I stink of what I

have lived is part of my legacy.

The blues is heartache, and our palms do not

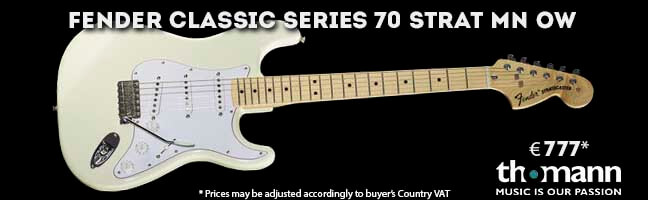

portray the glory, but the pain. At the controls of a cloned 73 Stratocaster and with double

shoulder strap, a loose waistcoat and triple fold jeans, Trout sings to the

point of weeping; not even about what has been lost, but about what will be

lost. And he is asked from the floor to also make his old, somewhat chipped, cream color Strat cry as well.

Me, my guitar and the blues defined everything on a cold rainy autumn night in

Madrid. This was the third song of the night, which is new in the repertoire of

this American dinosaur. Trout could not

even fill the Mon with people, but he created a night that was full of emotion,

eight years after his last visit to Spain. This particular tune seemed like a

song to a life that sought to take him a few years ago - because of that

bastard hepatitis - and that he has returned to fill with melodies, between him

and his six strings.

But ‘singing to life’ in a

bluesman is to cry hugging the neck and body of a guitar, to shout to the four

corners that there is a way to ward off evil, to give everything to the

audience - and perhaps beyond that there was nothing more than two or three hundred drunken freaks

attending Trout’s umpteenth vigil

against anxiety. No! The blues is ritual and ceremony, that was invented

for this, to make the guitar shriek between pedals and tremors. We unite to spend this moment together.

If pain ‘with bread’ is a

bit less painful, then the blues might just help you heal.

In the second

row, this scribe understood once more that just

like in flamenco, in the blues there is nothing for free. Trout told his

story starting from the sixth song of the setlist, or something like that. But he did it while he

exhibited his scars, and introduced a pile of subjects that explained, better

than I can here, how a legend like him

lost just about everything, but his life. That is, he lost the absolute worst

thing: the ability to make music by touching the frets and tearing away at the

plectrum.

He opened this part with Almost gone, with a country feel in the

backing vocals and harmonica, and then followed with a series of compositions

that represented a whole year - eight

hours a day - trying to relearn to play the old Strat. And after that, an

unstoppable series of blues styles: from rock to heavy, passing through

heartfelt ballads together with the singing along of the audience, at the

request of the protagonist.

It is very difficult to be

a genius, but Trout has been so twice, and literally. First in Canned Heat and in the Bluesbrakers of John Mayall; then solo with the support of his band: Michael Leisure on drums, Teddy Andreadis on keyboards and the

harmonica and the thick bass of the huge Johnny

Griparic.

Beginnings, tremors and

ecstasy in the audience;

crazy solos without end up on stage; reciprocal respect between the fans and

the artist; cries and laments. The

120 minute lesson that Trout gave this Wednesday in Madrid deserves a plaque in

hell; in the place where he never ended up.

Let them wait.