Robbie Robertson’s 10 best solos

By Sergio Ariza

45 years after The Last Waltz, from Guitars Exchange we have decided to take the opportunity to review our 10 favorite solos of Robbie Robertson’s career, either under the orders of Bob Dylan and Ronnie Hawkins or commanding the unforgettable The Band.

Ronnie Hawkins - Who Do You Love? (1963)

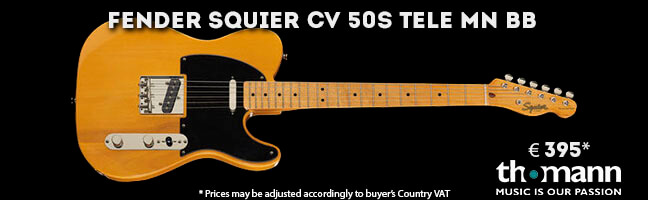

During a few months in 1960 Roy Buchanan was the lead guitarist of Ronnie Hawkins, shortly before Robbie Robertson had entered the Hawks as bassist. Robertson had not yet turned 17 but absorbed many of Buchanan's tricks like a sponge, such as the famous 'pinch harmonics', managing to get ahead for a few months as the first guitarist to record them, in the version of Further Up On The Road by the Hawks, recorded in late 1961 when Robbie had already taken over the position as the band's lead guitarist. But the best guitar work for Hawkins would come in early 1963 when they recorded their well-known cover of Bo Diddley's Who Do You Love? By then the Hawks' formation already housed all future members of The Band in their ranks, drummer Levon Helm (who had been with Hawkins since 1957), Robertson as lead guitarist, Rick Danko on bass, Richard Manuel on piano and Garth Hudson on organ, as well as Jerry Penfound on horns. At just 19, Robertson and his Telecaster enter the history of rock with the wildest and dirtiest solo ever put on a 45 rpm to date, and with a style that equals his masters, such as Buchanan, with the authenticity of a Hubert Sumlin.

Levon & The Hawks - Honky Tonk (1964)

By the end of 1963 the Hawks had clearly surpassed their leader, Ronnie Hawkins, so they decided to fly solo. The band wanted to test everything musically, from rock to soul, through blues, Honky Tonk, recorded in 1964, is a perfect testimony of an incredibly energetic band, with Richard Manuel at his best Ray Charles style and Robbie Robertson delivering a concise and spicy solo from the one minute and a half mark.

John Hammond - Down In The Bottom (1965)

Recorded in late 1964, although not released until June 14 of the following year, So Many Roads is a very important album in the evolution of blues rock, the white version of Chicago's vibrant blues. For this album John Hammond Jr. had three members of the Hawks, with whom he had fallen in love after seeing them in Toronto, Levon Helm on drums, Garth Hudson on keyboards and Robbie Robertson as the main protagonist on the lead guitar. The Canadian was in such a state that a young Michael Bloomfield, who also participated in the recording, played the piano, while the great Charlie Musselwhite accompanies them on the harmonica. A deluxe formation that nails it in songs like Down In The Bottom, where an unleashed Robertson shines through . Beyond the high quality of the album we can see its importance in the fact that Hammond invited his good friend Bob Dylan to see the recording and the next time he entered a recording studio, in January 1965, he would do it with his own electric musicians. Also in December of ‘64, Bloomfield would join the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, kicking off the 'revival' of blues among young white folks.

Bob Dylan - Leopard Skin Pill Box Hat (1966)

After recording his first two electric albums and shocking the folk public at the Newport Festival, Bob Dylan was left without guitarist Mike Bloomfield, who decided to continue with the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. So he remembered Robertson and invited him to play in his band, he convinced Dylan to take Levon Helm on drums and, soon after, Dylan was working with the Hawks full time. Their first tour together began in the U.S. in October 1965, the audience reaction remained hostile, but Dylan and his band were getting to the point of perfection. In the middle of the tour, on November 30, they entered the studio to record the masterful Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window? one of the artist's most powerful songs. Around the same time, drummer Levon Helm left the tour, tired of all the booing. He would miss one of the most mythical moments in the history of rock & roll, the world tour of Dylan and the Hawks during the first half of 1966, at the same time that Dylan recorded one of the most mythical albums of his career, Blonde On Blonde. The curious thing about the case is that Dylan decided to record it in Nashville, with musicians from there, taking only Al Kooper, the man who had played the organ on Like A Rolling Stone, along with Robbie Robertson, who would thank him for his trust with spectacular work in songs like this Leopard Skin Pill Box Hat, recorded on March 10, 1966, where he delivers another explosive solo. As a curiosity we can add that in the first few bars Dylan himself is in charge of doing a rudimentary solo, until Robertson enters with the force of a hurricane, shredding his mythical Telecaster.

Bob Dylan - Like A Rolling Stone (Live on May 17 1966)

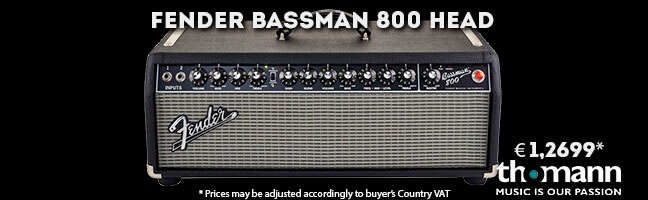

So we left off with Dylan and the Hawks about to leave for their mythical 1966 tour, the first part of it was through the U.S. and Canada, then they went to Australia and finally on April 29th they arrived in Europe. By that time, the concert was still divided into two parts, a first acoustic with Dylan singing with the only accompaniment of his Gibson Nick Lucas Special and his harmonica, and an electric second part, accompanied by the Hawks, with Mickey Jones replacing Helm on drums. The strength and rapport that Dylan and his band had reached at that time was absolutely telepathic, the culmination of that "mercurial sound" that Dylan heard in his head, with Robertson making powerful solos that become part of the song, as if they were conversations with his poetic lyrics. The best rock sound that had been heard to date (and maybe since then) came face to face with the incomprehension of the most orthodox folk audience who accused him of selling out. The most memorable moment came on May 17th, 1966 in Manchester, although it would go down in history as the Royal Albert Hall concert in London. Before starting the last song someone shouted: "Judas!" to which an angry Dylan replied "I don't believe you, you're a liar", then he turned to the Hawks and told them "Play fucking loud", before launching like kamikazes towards the most glorious version ever played of Like A Rolling Stone. Dylan doesn't sing the lyrics, he spits them out, playing with a black Telecaster he borrowed from Robertson. The guitarist listens to his boss and delivers his final solo at the end, an amalgam of notes that come out of his ‘59 BlondeTelecaster through a Fender Bassman like machine-gun shots ready to win converts to rock & roll.

The Band - To Kingdom Come (1968)

After the famous 1966 tour Dylan had a serious motorcycle accident and retired to Woodstock with his wife to live a family life. In February 1967 he invited members of the Hawks to work on new songs. It would be there, in a pink house shared by Manuel, Danko and Hudson, nicknamed The Big Pink, where the Hawks joined The Band and began to record their mythical first album, in addition to the famous Basement Tapes with Dylan. The spirit was to get back to their origins, to rural music and it had a lot to do with Robertson's new approach to the guitar, less inclined to take over and much more to help the song with fewer notes, in the best Steve Cropper style. Levon Helm returned to the band and the songs began to come out fluently, with Robertson as the main composer. To Kingdom Come is the only song in which he also sings on the album. You can see in his solo a calmer but equally influential style, something that would be reflected, for example, in Abbey Road by the Beatles, George Harrison being an avid fan of the band.

The Band - King Harvest (Has Surely Come) (1969)

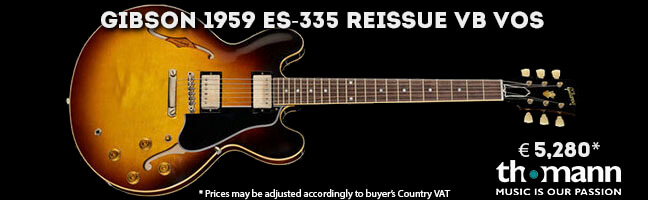

If The Band's first album was a revolution, the second was a revelation, something almost divine. Becoming the album where the roots music or 'Americana' style would look out since then. Robertson earned his doctorate as a composer on this album, writing or co-writing the 12 songs on the album, gems like Across the Great Divide, Rag Mama Rag, The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down and Up on Cripple Creek. But he may have left the best for the end, with the masterful closing on King Harvest (Has Surely Come), a song that ends with one of his most iconic solos, in a new fight between the guitarist and the composer, where he seems to fight against his own ego. If we pay attention to the wonderful live video, recorded in 1970, he may have recorded it with his Gibson ES-335.

The Band - Jemima Surrender (1969)

The influence of The Band's first two albums on rock was enormous but maybe the one who felt it the most was Eric Clapton who, after listening to them, decided that the time had come to leave Cream and even flirted with the idea of joining them. Listening to Robertson's solo on Jemima Surrender from his second album, one sees in its economy of notes the tremendous influence that The Band, and Robertson in particular, had on the first solo album of 'Slow Hand’.

The Band - Life Is A Carnival (1971)

The Band would never reach the heights of those first albums but the rest of their discography is full of great moments, like this Life Is A Carnival that opened Cahoots, the band's fourth album. It's a song built on a funk arrangement by the great Allen Toussaint who gives it a New Orleans flavor that Robertson plays with in his solo, mixed between the Creole and smokey horns.

The Band - It Makes No Difference (1975)

Northern Lights - Southern Cross, released in November 1976, was The Band's last major album before their farewell concert, The Last Waltz, recorded just a year later. It Makes No Difference must be considered among the band's great classics, from Rick Danko's incredible lead vocals to Robertson's and Hudson's incredible solos, on guitar and sax respectively. In particular, Robertson's solo is one of the most dramatic of his career, releasing pure pain from the strings of his red Strat (the same one that he would later bathe in bronze and would go down in history in The Last Waltz). It's an incredible solo in which he makes use of 'pinch harmonics' again and that fits like a glove with a song that seems to define a broken heart.