The guitarist and the composer

By Sergio Ariza

Robbie Robertson changed the course of pop music on a couple of occasions together with Bob Dylan and his Band. The first time by bringing the fire of rock and roll to the poetry of Like a Rolling Stone’s author, the second time by getting back the to the simplicity of American pop music’s roots at the moment when rock seemed headed to repeat the complex sounds of Sgt. Pepper’s. The first time he did it playing the guitar like a madman, and the second when his great guitar instincts had blended in with his spartan composing style, which led to the birth of what is known as ‘Americana’.

Jaime Royal ‘Robbie’ Robertson was born in Toronto on July 5, 1943, son of a Jewish card player that he never knew, and a Mohican mother. There’s a certain poetry to one of the fathers of the Americana genre being actually Canadian but also son of a indigenous North American. But let’s not digress, Robertson grew up combining the streets of Toronto with his Seven Nations Indian reserve. That’s where he learned to play guitar and almost more importantly, to tell a story.

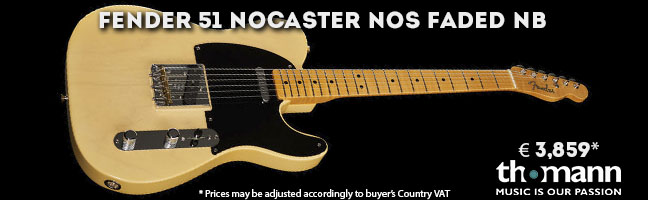

At 13 he was playing his first guitar, a Harmony Stratone. Surrounded by many older players he learned from them like a sponge. The first break in his career came in 1959 when Ronnie Hawkins signed him in his band, the Hawks. Robertson had just acquired a ‘57 Stratocaster, but the singer asked him to travel without it and when he got there he bought him a Telecaster, a model he would be faithful to for the next 15 years. Hawkins was a singer from Arkansas who decided to try his luck in Canada with his furious rockabilly. He made it to the stars up there, accompanied by a band of southern compatriots, among them, Levon Helm on drums.

So they started touring the southern states in the USA , the Promised Land of rock, where Robertson continued to learn his trade, thanks to Hawkins’ lead guitarists like Fred Carter Jr., and Roy Buchanan. When he became the lead guitarist in the late 60s, with barely 17 years behind him, Robertson was already a star in his own right as you can hear on songs such as Come Love (with Dionne Warwick singing backup vocals) and Further Up the Road in 1961, that relies on Helm’s lead vocal, which could be considered an original incarnation of what would later be The Band as by that time, Rick Danko had joined the group as bassman. Later, pianist Richard Manuel and organist Garth Hudson would join the band.

At the end of 1963, those five, and saxman Jerry Penfound would leave Hawkins, but not before recording one of the most essential rock singles ever, Who Do You Love, where Robertson and his guitar shine brightest, with the filthiest savage solo ever cut on a 45 to date, and a style that brings his great mentors together, like Buchanan, with the authenticity of a Hubert Sumlin.

After the departure of Penfound, the group became known as Levon & The Hawks, although their first recording in 1964, was under the handle The Canadian Squires. Leave Me Alone, with its Bo Diddley rhythm, has them traced with the Stones of the time. The Hawks had abandoned their leader, fed up with his musical restrictions and limited to just rockabilly, they wanted to broaden their horizons as musicians and play their own stuff. By then Robertson was already the main composer and Manuel began fitting in as lead singer, as you can hear on He Don’t Love You and Honky Tonk, recorded at the start of ‘65, and on which you can appreciate their love for soul and R&B, and Ray Charles in particular.

Yet, one of the key moments would come when John Hammond Jr. signed Robertson, Helm, and Hudson to play on his record So Many Roads from 1965. Robertson once again showed off his assets, to the point where Mike Bloomfield (also there) switched to the piano, and Hammond didn’t flinch in recommending the guitarist to his friend Bob Dylan. Dylan had just changed to electric guitar having recorded Like a Rolling Stone , and he had just finished a gig in Newport. But his guitarist, Bloomfield himself, chose to go with the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. Dylan went to see the Hawks play and was impressed, particularly with Robertson, so he decided to ink him for a gig he had in New York. Robertson put a good word in for his drummer, and so Helm was also there that day.

When Dylan decided to take both on tour, they said they wouldn’t go without the rest of the Hawks. That’s how one of the most important tours in the history of rock got started. One in which the man chosen by his fans as “the voice of a generation” was going to decide to rise up and play whatever he felt like without any restraints. As he said in one of his new songs, “I ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s farm no more”. The tour started with Dylan on acoustic and then later the band would come in and do a set on electric. He always ended up being booed and having objects thrown at him during the plugged-in part. By the end of the year Helm quit, he was tired of the booing. But before that, he took the time to record, together with the rest, one of the best singles of Dylan’s career Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?, possibly the rockiest live song of his career.

It was a good sound check they were doing live, the stars aligned, and the excitement, anger and magic appeared all at once, culminating in an English tour that heard a spectator yell, “Judas!” and Dylan shot back, “I don’t believe you, you’re a liar”, turned around and urged the band “ to play fucking loud” while they threw themselves like kamikazes on the most brilliant interpretation of Like A Rolling Stone in history. Robertson adds the final touch with an amazing solo and this is where you find some of the best of his career, as in Baby Let Me Follow You Down and Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues. Up until then Robertson had been the only band member Dylan had taken to Nashville to record the wonderful Blonde on Blonde, where his guitar is fabulous, on gems such as One of Us Must Know, Leopardskin Pill-Bow Hat, Pledging My Time, Obviously 5 Believers and Visions of Johanna.

After surviving the most schizophrenic tour in history, where folks fans paid for tickets to boo the artist and his ‘wicked’ rock band, they returned to the U.S.. On july 29, 1966 Dylan had a serious accident and everything ground to a halt, he sought refuge in his house in Woodstock, NY, and he withdrew from public life. When he got better he called up the members of the Hawks to join him once again. That’s where the second revolution began, away from the psychedelics and other dominant trends, they began to write new much simpler songs where rock, country, blues, folk and R&B mixed to perfection stewed up in the legendary pink house where some of them lived, and where alongside Dylan, they laid the first stone in the Americana movement of country/rock and went back to their roots. The result was known as The Basement Tapes, and wouldn’t see the light of day (legally) until 1975.

But what did see the light of day was the first record of the group that became simply, The Band. A name that seemed to be an example of modesty in an era when bands were called Chocolate Watch Band and Strawberry Alarm Clock. As far as the members of the group went, they looked like lumberjacks instead of rock stars. Music from Big Pink is one of the most essential records of the 60s, as well as the album in which The Band sounded more like a band, with the job of composition equally shared between Manuel and Robertson , besides the three Dylan songs. Yet the song remembered as piéce de résistance was none other than Robertson’s The Weight. It is a perfect example of how the guitarist knew how to adapt to being composer and changed his signature style for one that moves to what the songs demands, something along the lines of Steve Cooper or Curtis Mayfield. The effect of the album was tremendously impressive with players such as Clapton and George Harrison. Clapton decided to quit Cream after hearing it, and wanted to be part of The Band. The influence on the Beatle was obvious, with Robertson’s guitar sound on songs like Tears of Rage, with his Tele passing off as a Leslie, and the light touch of the slide in In a Station, which are reflected in the sound of Abbey Road.

All of this was about to get bigger yet with the release of their 2nd record, The Band. Robertson begins to take the reins writing or co-writing the record’s 12 songs, making up the A side that seemed like the band’s greatest hits, Across the Great Divide, Rag Mama Rag, The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down, Up Cripple Creek, written by Robertson himself, and his work with Richard Manuel on, When You Awake, and Whispering Pines. If we add to this a song on side B, which is the best of the whole album, King Harvest (Has Surely Come), we have one of the most essential records of root rock. On this last song the guitarist rips one of his most iconic solos, in a new fight between player and composer, where he seems to be fighting his own ego.

The 3rd record, Stage Fright, was released in 1970. It still reached that highest of levels, but signs of fracture within the band began to show. A dark record, with Robertson’s lyrics focussing on this strange feeling between them. The country boys had become millionaires and adapted a rock star lifestyle, where some band members fell to heroin addiction. This was the last record in which Manuel is believed to have had some part in the composition. A year later, Cahoots became their first skid, in spite of numbers like Life Is a Carnival. The live Rock of Ages was a commercial success and allowed Robertson to get back to his role as active guitarist as you can see on his version of Don’t Do It by Motown.

The first real sign that things weren’t well was Moondog Matinee, a record of old covers which lacked the chemistry that had made them famous. In 1974, Dylan came out of retirement and returned to the road after 8 years. His players were the same as before but, this time, they were already stars by their own account, and on the set lists were some of their songs. Despite not being their best tour, it was a fabulous success, the jeering had stopped, and it contributed to a record called Blood on the Tracks, where his revision of All Along the Watchtower is superb with Robbie let loose. They also recorded Dylan’s new album Planet Waves, where Robertson went from his faithful Telecaster from the 50s and 60s to a red ‘54 Stratocaster. It would be his main instrument for the rest of his career in The Band.

Northern Lights - Southern Cross was a good return, with songs like Acadian Driftwood, Ophelia and It Makes No Difference, with another great solo from Robertson, but it also came to prove that something wasn’t well with the band. Tired of the destructive habits of his mates, Robertson decided to call it quits, have one last show, so he got in touch with film maker Martin Scorsese to make it something special. At first it was going to be his own show, sprinkled with appearances by the two main men in his career, Hawkins and Dylan, but it ended up growing into a colossal mega-gig with giants such as Neil Young, Van Morrison, Clapton, Muddy Waters, Neil Diamond, and Joni Mitchell.

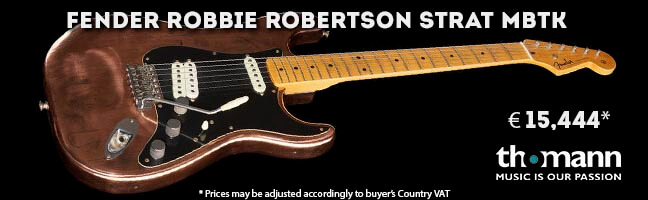

The show was held on November 25, 1976 in San Francisco and Robertson treated himself by bathing the Stratocaster in bronze. That got him a different sound and a guitar that weighed 10 pounds heavier. Still, that axe was able to speak face to face with the ‘God’ Clapton and went down in the history of rock. The Last Waltz was the perfect cherry-on-top to a legendary band. Later would come the disputes, the reunification without Robertson, his acting career and his sound tracks for Scorsese, and an interesting solo career besides. But let’s do what Robbie himself did in his autobiography and finish this at the highest moment . The moment when rock aristocracy pays homage to their band.

(Images: ©CordonPress & http://robbie-robertson.com)