The third revolution of jazz guitar

By Sergio Ariza

When The Incredible Jazz Guitar of Wes Montgomery was released in the

early 1960, the jazz world, specifically the jazz guitar, experienced a seizure

that it had been expecting for a long time. Since the tragic disappearance on

March 2, 1942, at only 25 years of age, of the great Charlie Christian, the jazz guitar was orphaned by a similar

leader, someone capable of putting the instrument, always relegated by the

winds, in the front, and to be equal with some of the giants of the time such

as John Coltrane or Miles Davis. Wes Montgomery was that

leader, the man who revolutionized the jazz guitar forever as before only two

figures had done, Christian himself and Django Reinhardt. As Joe Pass said, " there

have been only three real innovators on the [jazz] guitar- Wes, Charlie

Christian and Django Reinhardt."

But before Montgomery came out of

nowhere to revolutionize his instrument there was little known about his most

interesting past. John Leslie 'Wes'

Montgomery was born on March 6, 1923 in Indianapolis. Despite being part of

a family of musicians - his other two brothers also played instruments - the ‘middle’

Montgomery did not seem especially inclined to play. His brother Monk had bought him a four-string tenor

guitar at age 12 but Wes had not paid much attention to it. In 1943, when he

was 20 years old, he got married and started working as a welder. That same

year he went to a dance with his wife and someone put on Charlie Christian's Solo Flight. Something stirred inside

him, his life changed suddenly and he knew what he wanted to do with it from

that moment. The next day he bought a six-string guitar, an amplifier and a

Charlie Christian record, and prepared himself to learn all his solos. Although

he liked Django and Les Paul, after

listening to Christian he had such a big revelation that for a year he only

listened to his music. During the day he continued working but, at night, when

his wife went to bed, Montgomery stayed practising until dawn. In order not to

wake her, he began to play with his thumb instead of with a pick, and that

became one of his trademarks.

He finally got so good at playing like

Christian that he got a job at a club playing his solos. Over time he began to

gain fame locally and when in 1948 the band of Lionel Hampton played in Indiana, he got a position in it by impressing

the vibraphonist. For two years he traveled around the country with Hampton,

although his fear of flying made him drive from city to city, no matter how far

away he was. During his time with the band he played with musicians such as Charles Mingus or Fats Navarro, which made him a much better musician and not just a ‘copy

of Christian’. Even so, life away from his family was tiresome and he returned

to Indiana in the early 50s, where he met up once more with his brothers, Buddy and Monk, and played again for

clubs in the area. Together they traveled to the West and Buddy and Monk formed

the Mastersounds and signed for

Pacific Jazz. In 1957 Wes went with them to record an album with the promising

trumpeter Freddie Hubbard. But while

his brothers stayed in California, Wes returned, once again, to Indiana.

There he continued working during

the day and playing at night, spending most nights awake on a diet of

cigarettes and alcohol. His style had been completely perfected, his characteristic

use of the octaves and his soft and sensual touch with the thumb, instead of

with a pick, made him a local attraction. So much so that in 1959, while

playing in the area, Cannonball Adderley

decided to go and take a look. The saxophonist was at the peak of his

popularity, as he was a member of the legendary sextet Miles Davis, with John

Coltrane, and led his own quintet. After seeing the guitarist he was impressed

and as soon as he had a moment spare he went to see Orrin Keepnews, owner of the Riverside label, to urge him to sign

him immediately. Keepnews had heard of Montgomery through Gunther Schuller who also sang his praises. So he took the next

plane to Indiana and stood in the Missile club to hear the genius. He was not

disappointed; he signed a contract that night and on October 5 Montgomery was

already recording his first album for the label. As could not be any different,

one of the songs the guitarist wrote was Missile

Blues, about the place that had changed his life. On that album Wes used a

Gibson L-7 borrowed from Kenny Burrell

plugged into a Fender Deluxe.

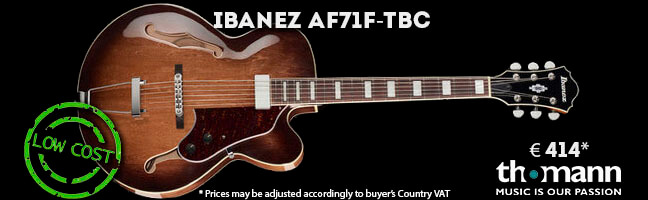

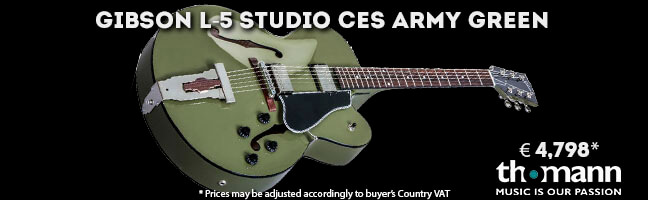

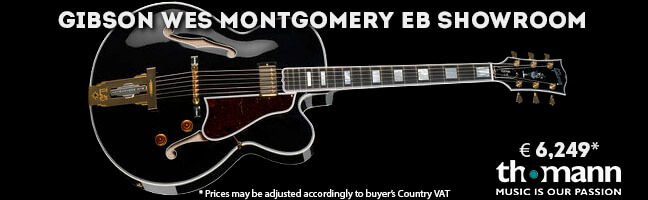

It was one of the few occasions in

his career when he did not play the guitar most associated with his name, the

Gibson L-5 CES. So much so that Gibson would end up making three custom guitars

of this kind especially for him. The only modifications were that they had a

single pickup instead of two, and it was placed inside out. His favorite

amplifiers were a Standel Super Custom XV and the Fender Twin Reverb. Of

course, Montgomery was not one to pay too close attention to the equipment,

which he thought was nothing more than a tool to do the job; he considered the

magic to be in his fingers.

It was that magic that appeared in

abundance when a few months later came The

Incredible Jazz Guitar of Wes Montgomery, recorded with Tommy Flanagan on piano, Percy Heath on double bass and his

brother Albert, on drums. The record

turned him into the most famous guitarist in the world of jazz and earned him

the recognition of both critics and the public. The album was accompanied by a

few words from the critic of Down Beat,

Ralph J. Gleason: "Make no mistake, Wes Montgomery is the

best thing that has happened to the guitar since Charlie Christian".

Everyone who listened to wonders like Four

On Six or West Coast Blues, his

particular Solo Flight, seemed to

agree.

But the tremendous impact of the

album did not change Montgomery’s personality much, the fact of becoming ‘the

new star of the guitar’ did not seem like a big change for the practical

musician - before he was unknown and did not have a penny, now he was a star

... and still did not have one. So he got down to work and took advantage of his

popularity to record frequently, either as a leader or as a collaborator. Thus

came two great projects with Nat

Adderley, the brother of Cannonball, in the remarkable Work Song and with Milt

Jackson in Bags Meets Wes. But,

undoubtedly, what he most excited about was the call from his idol, John

Coltrane, whom he came to describe as "something similar to a God for

me". In a certain way, Wes was taking to the guitar many of the stylistic

advances that saxophonists like Coltrane or Sonny Rollins had implemented in their instrument. So having

Coltrane's recognition was something memorable for him. They played together at

the Monterey Jazz Festival in 1961 and at the Jazz Workshop in San Francisco

that same year. Despite having a top lineup with them two plus Eric Dolphy, McCoy Tyner, Reggie Workman

and Elvin Jones there is no

recording of these historic concerts.

His time in the Coltrane group was

his last experience as a collaborator, as he was the band leader for the rest

of his career, winning all possible prizes as best guitarist of the year in

specialized publications. In 1962 came the fundamental Full House, recorded live, in which the title song is a highlight, and

a composition of his; and the Blue 'n'

Boogie Dizzy Gillespie cover, containing

one of the best solos of his career.

But, in 1964, Riverside went

bankrupt and Wes signed up for Verve where they surrounded him with orchestral

and string arrangements by Don Sebesky

and producer Creed Taylor. His

credibility among the most purist jazz world was affected but his finances

improved considerably, with his albums regularly entering the Billboard charts.

His distinctive tone, octaves and taste for melody were still there, despite

the change of accompaniment. He also continued to alternate orchestral records

with other more jazz oriented like the excellent Smokin 'at the Half Note,

which Pat Metheny said was the best jazz guitar

album in history, or The Dynamic Duo,

along with organist Jimmy Smith. But

his approach to pop on albums like California

Dreaming or A Day In The Life,

with things close to ‘elevator music’, made many say he had sold out. Wes

himself never saw it like that, he gave people what they wanted and he

continued to demonstrate in his concerts that he was unmatched when it came to

playing jazz. But at the moment his career hit peak popularity, on June 15,

1968, a heart attack ended his life.

Just as he learned to play by

copying Charlie Christian, a whole new generation of new jazz guitarists grew up

copying him. Among his disciples were George

Benson, Pat Martino or Pat Metheny,

who came to recognize that when he began to play there was a moment in which he

played exactly like Wes, with thumb and octaves included. But his influence was

not limited to the world of jazz, the decade of the 60s turned the guitar,

specifically the electric, into the most popular of all instruments and so we

could say that Wes Montgomery was the main figure in jazz, as BB King and Jimi Hendrix were for blues and rock

respectively. Certainly, Wes Montgomery had the appreciation of these other two

giants and if their feelings and words are not known just listen to Hendrix's Villanova Junction in Woodstock, or

listen to the words that B.B. King said before a concert in Indianapolis:

"There was never a better guitarist

than Wes Montgomery."