A Reverential Turn

By Paul Rigg

It was always going to be interesting to see where Ry Cooder would head next, following his 2012 explicitly

politically-oriented album, Election

Special.

At first sight it might seem that Cooder has ‘been

reborn’ in true Bob Dylan style, as he references Jesus, wrote and sings the

title track, The Prodigal Son, and

covers Blind Willie Johnson’s Nobody’s Fault But Mine.

But that interpretation would be

mistaken because as Cooder himself explains, he is not religious but ‘reverential’.

Part of the reverence is clearly towards the artists who wrote eight of the 11

songs on this album. But he has also said that ‘Reverence’ is a word he heard his granddaughter’s nursery school

teacher use when talking about some of her classes: ‘We don’t want to teach religion,

but instill reverence’ she said; and at that moment he realised that this

closely described the feeling of this music.

Specifically, Cooder says that he wants

to be “a conduit for the feelings and

experiences of people from other times,” and he impressively achieves this on

this album not just through the lyrics, but through returning again to the

music of bluegrass, black gospel, folk and blues.

Ry Cooder and his son, Joachim, can also be said to have produced a political album which,

because of its subtlety, is perhaps even more powerful than the previous. This

is the case, firstly, because while gospel music has great melodies it also

carries with it an underlying drive for social justice and, secondly, because

tracks like Gentrification reference

the socially downtrodden and others, like Everybody Ought to Treat A Stranger

Right, hark back to a time when it

felt like the right thing to do was to welcome a stranger, rather than demonise

them.

The

album kicks off with a cover of the Pilgrim

Travellers’ Straight Street,

which uses a mandolin to set the spiritual tone before Cooder reminds us ‘not

to lose our way or our souls’. The track also contains “a rollicking blues chopped out on a spiky electric

guitar, with a solo that comes across as a tribute to Chuck Berry”

according to Uncut magazine. More religious fare is offered with Alfred Reed’s You Must Unload, which talks about the

importance of leading a good life and criticizes

“money-loving Christians who refuse to pay their share” and hypocrites who will

“never get to heaven in [their] jewel-encrusted high-heel shoes.” More

spiritual direction is offered on Cooder’s reworking of Carter Stanley’s Harbor Of

Love, which references the after-life; but by far the most oustanding track

on the album is his powerful interpretation of Blind Willie Johnson’s 1930s tune, Nobody’s Fault But Mine.

Cooder’s cover of this song

begins with some eerily haunting synth, which was reportedly created by his son

Joachim. Cooder slows the song right down before entering with a vocal that

sounds like it has been dredged up from some dark corner of hell. He then

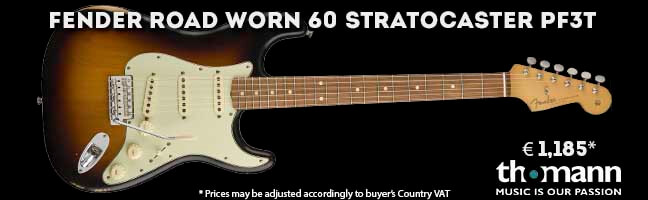

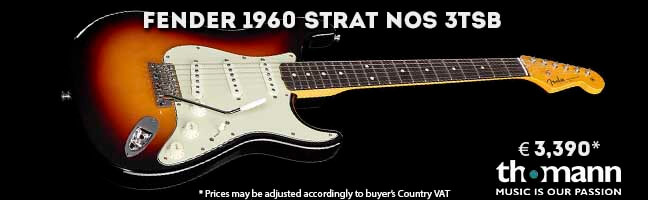

introduces his legendary slide guitar, possibly his Coodercaster, a modified

60s Strat, to produce a cover version that is surely destined to become a

classic in his repertoire.

The penultimate track Jesus And Woody is a warm tribute to Woody Guthrie, one of Cooder’s heroes. Here, Cooder dreams of an

encounter between Jesus and the much-loved activist-folk singer, singing that

“they’re starting up their engine of hate,” while Jesus beseeches "you good people better get together, or you

ain't got a chance anymore."

This powerful album might easily have ended on a

political note but Cooder clearly felt strongly about bookending it with a

return to the theme of reverence, and so he closes with another gospel number:

this time with a more rock-oriented cover of William L. Dawson’s In His

Care.