When Duane Allman found his sound

by Alberto D. Prieto

Music

is pain, a lament for failing to unite the broken pieces. Music is born from a

broken heart and from absences. It is expressed through the personality of

suffering, be it as a solo artist or in a band...there is always a moment of

solitude, silent dialogue with the notes that brings tears to the eyes and

causes blisters on the fingers. Music is pain.

Howard

Duane Allman

(20th November 1946, Nashville, Tennessee) had, well, a painful

adolescence, because from dusk till dawn he sat in a chair looking for the lost

sound. Not even lost; never found. What severe pain for a musician to never

find his music. Because Duane Allman was already a star of the musical scene before the world had a chance to

see it and died almost without him being able to warm up to his audience. Yes,

he had time to find his sound. However, since music is pain, just when the

alchemy of his light was created he had to leave his legacy to posterity.

It is

like distant stars in the sky. Born without anyone noticing, and once they

reach their zenith the sky, in reality they no longer exist. Duane Allman left his relatives the

material, endless income royalties for his work, and most importantly, a new

paradigm of white blues and southern rock, pride at the bar,

calmness in the eyes, aplomb in the interpretation of vital verse. And a sound:

born from pain, blisters and fever. From tirelessly chasing a dream that

disrupted his sleep each night, causing him to forget worldly

obligations…fulfilling his destiny.

After

seeing B.B.

King live in concert at the young, impressionable age of 13, Duane and his younger brother

found their calling in life. The boy destined for the ephemeral glory tore

through over the vinyls of Muddy Waters and Robert

Johnson he

managed to collect at home and dismantled and sold his mother’s Harley piece by

piece... With the money earned from this, he purchased his first guitar. Twelve

years later, he would die beneath another Harley that, cursedly, trapped him

like a finger on the fret and slid his body on the tarmac.

If at

the age of 15, his fingerprints were nearly erased by crushing the strings

against the neck of a Telecaster, before the change of the decade, the young Duane was already a remarkable studio

musician, whose abilities had drawn the attention of the greatest, from coast

to coast. From Florida to California. The failure of Hour Glass, the first band he formed

together with his brother Gregg

in Los Angeles, left a legacy: Fame Studios hired them to accompany their recording sessions for singers in

their catalogue.

The

secret to this small triumph he kept hidden in a little bottle of drugs that

carried him to the precise fret, but in reality, what that bottle did was orbit

his Strat and bring it to the

confines of a new universe of sounds. With his guitar and him, along came new

listeners and accompanists. During this journey, singers such as Aretha Franklin or Wilson Pickett joined along. And others,

such as Joe

Walsh,

asking for the opportunity to test the weightless flotation of the slide.

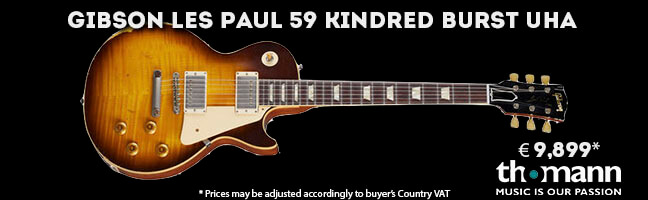

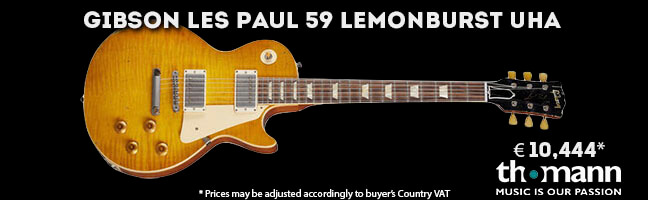

Duane formed a new band with

five more friends, amongst them, yet again his brother Gregg. High on endless, drug-fuelled

sessions filled with whiskey and improvisation along the chords, Duane Allman, guitarist (one of them)

and soul (including after his death) of The Allman Brothers Band, packed a Les Paul from ‘59 in his luggage and travelled to

New York in the magical year of ‘69.

Everything

had led up to that change of decade, a number (69) of back and forth, up and

down, perfect, that concentrated the palindromic tension of blues, rock, pop, psychedelic, jazz, soul and country. A crucial, tipping point

year that would give birth to the dawn of progressive rock, heavy metal, concept music, funk, reggae and other fresh new

sounds. Thousands of paths had orgasmically converged during the flower power parties

that characterised the last years of the 60’s and, like every crescendo, its

subsequent explosion would germinate in endless new paths.

One of

them that Duane

Allman

carried and kept hidden, like a treasure map, was a little bottle of Coricidin. It was the New York of Tom Dawd, the producer of Cream. Duane wanted to show him that if

the three members of Clapton were

the Holy Trinity, the Allman

band weren’t a group of six by coincidence.

The Allman Brothers arrived with Butch Trucks (whom today, his nephew Derek plays the slide with mastery in the

current formation of the Brothers)

and Jai

Johanny Johanson (another 'session man'

from the days of Fame) with two drums –the light

needed power-, Dickey

Betts as

(the other) guitarist and Berry Oakley on the bass. They arrived to The Big Apple feverish from the blues, with the mercury about to

burst, filled with progressive ideas. The strawberry-blonde man with a southern

moustache arrived, exploding like a supernova, restless to harvest the seeds he

had planted months ago, when all his moods finally came together in a delirium:

sick in bed, he had heard, amongst fever sweats, the dreamlike slide of 'Statesboro blues' played by Taj Mahal. That forgotten cover hit

the precise fret, and Duane,

after emptying the bottle of pain reliever, no longer wanted to lower the heat

of his fever anymore. The Coricidin

on his ring finger had inaugurated his authentic sound, the sweet slide of Duane Allman that, garnished with the

spicy sharpness of the volume knob turned to maximum, served to teach

everything to an entire generation.

Rehearsing

in cemeteries, soaking the inspiration in liquors and other herbs they carved

out the grooves of two LPs full of inspiration, officially launching

ceremoniously the luck of white blues and southern rock. With nods to folk and the beginnings of progressive rock—with a Gibson ES-345 semi-hollow and a Les Paul Cherry Sunburst. With eternal

instrumentals filled with different melodies that forged approaches, junctions,

endings, outcomes and private sub-stories to stir up passions of their own.

With little pearls at the bottom of a glass of bourbon. With a sound so unique

and necessary that it hurts to imagine what would have become of us without

him. And what we would have done before him.

Duane not only lent his surname

to the group. With his ability and genius he also gave to life to guitars that

until then were unaware of what they were capable of.

The

most intense glow of the Allman Brothers was, in any case, on stage. Therefore, no one was surprised that 'At Fillmore East', their next album, a live

recording from March ‘71 on that stage in New York, was like registering an

explosion and, vinyl groove to groove, in high definition. It was released in

the summer: only three and a half months before Macon, Georgia, when all the

band members would go out to eat lunch during a break of recording sessions

that would later fill the posthumously released 'Eat a Peach'. That part of the sound

legacy, Duane left behind in the masters at the studio. Yet there was another. Even

more important. The imprint of his sound he left behind in the greatest

recording studios in the business of the six strings.

Harrison denied it (of course, for

damage control), but some say that Pattie Boyd rebuked Clapton, amongst liquors, that she was so amazing she had inspired 'Something' by George.

They say that, in pain, he alleged that, bit by bit, he knew how to win and

snatch the lover from the arms of the ex Beatle composing for her the great 'Layla' that gave name to the only disc

of Slowhand with Derek and The Dominos. And they say that however

almighty the god

of the guitars

was capable of stealing, dethroning the blues from even the black people of

Mississippi, it wasn’t until he convinced Allman

to

accompany him in the recording sessions of the LP that 'Layla' began to take shape. To the extent that

the powerful personality of the song, which he rounded out—and made it so

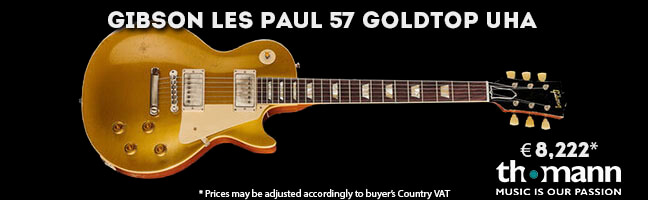

worthy that Pattie could boast of being his muse— was the work of Duane. For starters, he brought

out the brutal riff

from his ’57 Les Paul Goldtop that begins the song. Converting

a resounding version of regret --"there is nothing I can do..."--

from Albert

King in 'As the years go passing by' into one of the most

recognizable arrangements ever undertaken by six strings. And as it finishes, Allman improvised with the slide alongside the piano with Jim Gordon the closing, the cry of a

thousand cats coming out of the bottle of Coricidin that the Southern devil fastened with

his left ring finger.

Clapton

doesn’t

have much to say, of course. If music is pain, that a redheaded demon brat

perfected a god’s creation, that is extreme pain.

The

short career of Duane

Allman, two

studio albums and a live recording with The Brothers, did not prevent him from reaching the

category of a magician, despite meeting his light too soon. His doglike

appearance, his predilection for mixing substances and sound, leads one to

believe that there was something of an alchemist in his ability to be

ubiquitous and that his six strings were (and still remain) in various worlds: blues, southern rock, jazz and soul... Duane drank those liquors since

he was a youngster at the gramophone in his home and he fed himself from those

essences, making them his own. And in his combustion engine, he made a hidden

and unmistakable mix, like the sound of a Harley.

Slide,

everything slides, even the motorcycle on top of me. And afterwards, the sound

of absence. Music is pain. We arrived too late to your sound; you had already

left. But here, you keep on shining.