A blues giant

By Sergio Ariza

Freddie King was a giant in every sense of the word, 2 metres tall and 136 Kg heavy. The minute he took the stage it was impossible to look away from this musician who brought together 2 greatschools of blues in history: Texas blues and Chicago blues, and proved to inspire a new generation of phenomenal British rock/blues guitarists like Clapton and Peter Green. He never got the recognition that his explosive music deserved but since his death his light has nothing but grown to where he resides with the other 2 blues kings, B.B. and Albert King.

The youngest of the 3 blues kings, born in Texas on September 3, 1934, some 10 years after B.B. and Albert. As King himself so aptly put it, he was born into a blues family, from his mother to his uncles, they all played and sang the blues. He grew up poor in the cotton fields idolising T-Bone Walker and B.B. King, he had his first guitar at age 5, but it was his encounter with Lightnin’ Hopkins which pushed him to be a musician. However, it was his love for Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf that got him to move to Chicago, promised land of electric blues. This was where, together with other hungry wolves like Buddy Guy, Otis Rush and Magic Sam, they created a vibrant scene on the West Side. His sound was unmistakable from the start, mixing Texan and Chicago schools with riffs, chords and melodic phrasing blending the percussion Chicago style owned by Wolf, whose band he played in for a short stint. At the time King was one of the best known ‘headhunters’ in the city; he sought out other guitarists, climbed onto the stage with them, and they fought a duel. Yet even then, when he went for an audition to the city’s leading record label, Chess, they turned him down saying he sounded too much like B.B. King.

King had arrived to Chicago in 1952, at age 18, and after sneaking into all the juke joints on the South Side to see the greats, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, T-Bone Walker, Elmore James and Sonny Boy Williamson, he formed his first band, called The Every Hour Blues Boys. In 1956 he recorded his first record as a lead with the label El-Bee Records, Country Boy, a duet with Margaret Whitfield. But the best of Freddy was still on the stages of the West Side. It wasn’t until, rightly so, he signed on the King label in 1960, led by Syd Nathan, that he found the perfect place - although his records would be released on the subsidiary Federal Records.

On August 29, 1960 Freddy (at the time he still hadn’t changed to Freddie) went to the studio with a remarkable band, made up of Bill Willis on bass, Phillip Paul drums, Sonny Thompson on piano and Freddie Jordan on rhythm guitar. They recorded songs that would become classics in his career: Hide Away, I Love the Woman, Have you ever Loved a Woman?, I’m Tore Down, and Lonesome Whistle Blues. The last few would make up the base on his first record, Freddy King Sings, while the first, an instrumental based on a song by Hound Dog Taylor and Peter Gunn by Henry Mancini became hits on the R&B charts, and this was much stranger for a bluesman, with a song pretty enough to appear on the pop charts, being one of the first blues songs to achieve that.

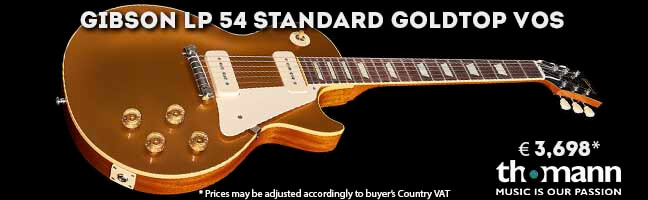

It is not surprising that in his company they took note of this and decided to record an album of instrumentals where you’ll find numbers that form part of a repertory that all new good guitarists would need to play should they want to be regarded as such. Gems such as, The Stumble, San-Ho-Say, and Sen-Sa-Shun, that make up what might be the best record of his career, Let’s Hide Away and Dance Away with Freddy King, a record that over time would serve as an induction test for one of the most prized jobs in Brit blues, the guitarist for John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, the first was Eric Clapton who made Hide Away his own in his brief stint with the band, later he would be replaced by Peter Green who would do the same with The Stumble, and finally, the young Mick Taylor would make his debut at 18 with another King number, Driving Sideways. It seems like they also took note of the guitar he was playing, a Les Paul Goldtop from ’54 with P-90 pickups plugged into a Gibson GA-40 amp.

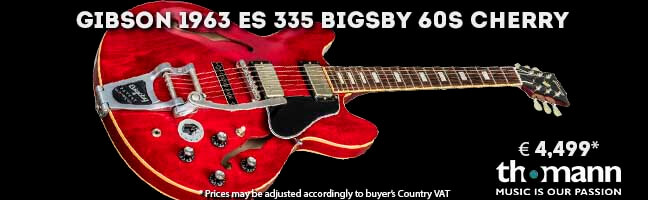

1961 was his best year commercially with 6 singles reaching the R&B charts on Billboard. King’s style, with the force and strength of his instrumentals along with that slow rhythm and the soulfulness of his singing, as the songs mentioned above or Christmas Tears, he became loved by all types of audiences. In 1962 he made a decision which would take him away from the path of success: to quit Chicago and go back to Texas to raise his kids. Despite still recording at Federal until the mid-60s the material didn’t reach the numbers of his first records, with efforts to fuse with other styles like the bossa nova and surf. Yet still, he did some remarkable things like Freddy Gives you a Bonanza of Instrumentals in 1965, the second instrumental record in which he plays the guitar normally associated to him: a Gibson ES-345. But success didn’t come knocking again and King went on tour with some of the greatest R&B names of the day like Sam Cooke, Jackie Wilson, and James Brown, where he opened for one the most legendary concerts of his career, on October 24, at the Apollo Theatre in New York city, immortalised in Live at the Apollo.

In 1966 his contract with Federal ended and King went without recording for 2 years until he was rescued by King Curtis, who inked him on his label Cotillion Records, a subsidiary of Atlantic Records. With the saxman as producer they recorded 2 albums, Freddie King is a Blues Master in 1969 and My Feeling for the Blues in 1970, the 2 most soulful records of his career. By this time King already had himself a new public - rockers -, and stopped playing in the shabby juke joints and move on to places like the Fillmore. And by then Freddy had already become Freddie.

The second golden age in his life came when he signed for Shelter Records, a Leon Russell label, another of his followers inside the rock world. They treated him like a star there, and he would record the essential Getting Ready in Chess studios in Chicago, which was released in 1971. He played alongside elite players like Russell on piano, Donald ‘Duck’ Dunn on bass, and his mate at Mar-Keys, Don Nix who was responsible for the success of the session, Going Down. King shows his ability to adapt his style, like hand to glove, to the new times and delivers a record with a clear link between blues and rock from the last few years. He made 2 other records on the same label, Texas Cannonball (the album that gave him the nickname that would always be remembered) in 1972 and Woman Across the River the following year.

In 1974 his most renowned pupil, Eric Clapton signed him to RSO Records and Burglar was released, a formidable record where the ‘Texas Cannonball’ and ‘Slowhand’ would exchange licks, with Clapton declaring his undying respect for King. The next year Larger Than Life came out, but he wanted to profit from his newfound success among the rock public (the public that made Grand Funk Railroad mention him in We’re an American Band), King took his excesses to the max. With over 300 gigs a year King kept a diet of mainly Bloody Marys (a food source in his opinion) and his body said enough. In 1976, while he was playing in New Orleans, he fainted during a solo and had to be hospitalised. He had several stomach ulcers but King kept on the road and played in New York on Christmas Day. Upon his return to Dallas, he was admitted to hospital again and died December 28, 1976 at the age of 42.

His muscular guitar tone inspired a legion of musicians, from the ones mentioned like Clapton and Green, to his countryman Stevie Ray Vaughan, but we mustn’t forget his spectacular and heartfelt voice. His music served as a bridge between blues and rock, and was one of the first to hand a mixed race band, breaking the stereotypes from inside the blues world. He was the youngest, and the first to leave the 3 kings of blues, but no-one doubts that his legacy is as indispensable and influential as the other two.