The personal blues of Taj Mahal

By Sergio Ariza

Taj Mahal is one of the most important blues figures of the second half of the 20th Century, but to frame his career in one musical genre would be too simple given that Henry St. Clair Fredericks, born in New York 1942, has had many playing styles: folk, calypso, reggae, rock, and R&B. What he’s done with his approach to playing blues has been criticised by some purists who don’t seem to get his joyful way of seeing the blues as music open to as many influences as possible, making it something personal and his own.

Of course his beginnings weren’t anything like those of legendary bluesmen, he didn’t get near any plantation, or grow up poor in the South. His family was high middle-class, and his father was a jazz musician with Jamaican origins , who Ella Fitzgerald called ‘the genius’. As a boy he listened to all kinds of music, but like most teens of the 50s, he became obsessed with the blues, acoustic as much as electric, and the early rock&roll of Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley. After starting agricultural college he began to play and adopted the name he still wears today, Taj Mahal.

After graduating, he chose to focus on music and went to California to form a band with the most talent and least luck of the 60s. They were The Rising Sons and in the group was a young gifted fellow who went by the name of Ry Cooder. The group got together after a performance by Taj Mahal and his boyhood mate Jesse Lee Kincaid on their acoustic guitars at Ash Grove in L.A.. It was in March 1965 and Cooder who had been playing since he was 4 and had even given classes to Kincaid asked if he could join the band. Shortly after, bassman Gary Marker hooked up, and to top it off, Ed Cassidy on drums. By May they were causing a sensation on the L.A. scene, where it was thought they would be the next big thing after The Byrds, to rise to stardom. If Roger McGuinn’s Byrds were the American answer to the Beatles, the Rising Sons were the same to the Rolling Stones, with the booming voice of Mahal and the dexterity of young prodigy Cooder. The way they modernised blues led to the Stones themselves coming to see them on a few occasions, and they wouldn’t forget it, a few years later Cooder would be the replacement of Brian Jones and invited Mahal to one of their most recorded shows. But we’ll get to that.

In July Columbia signed them on and by September they were in the studio with Terry Melcher, the Byrd’s producer. It was at this time when the first changes were made in the band. Cassidy injured himself while playing one of Taj Mahal’s biggest songs, Statesboro Blues by Blind Willie McTell, and Chris Hillman recommended his cousin Kevin Kelley to replace him.

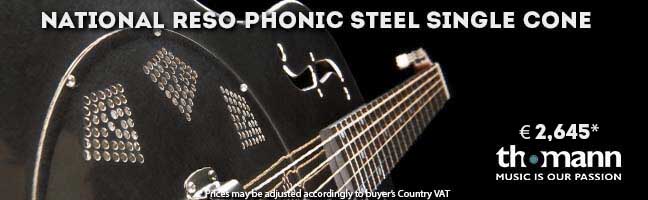

During his stay with band Taj Mahal recorded several songs, mostly versions, which he would later take up to give his solo career another shot. The group was especially good at old blues covers, be it electric versions such as the aforementioned Statesboro Blues or If the River Was Whiskey (Divin Duck Blues) by Sleepy John Estes, or acoustic numbers where Mahal also leaves his mark on his National Steel-body guitar . But when it came time to pick a single that would do for release, Melcher chose two songs that were more folk rock, sung by Kincaid, something he never understood, as everyone knew it was Mahal who had the really good voice. It was edited in February of ‘66, it failed beyond repair so the company decided not to release the record, and it didn’t see the light of day until 1992 under the name The Rising Sons featuring Taj Mahal and Ry Cooder.

Despite all this, the band was still opening for the big acts like The Temptations or Otis Redding himself, at one gig many years after, Mahal would remember it as the greatest thing he’d ever witnessed in his whole life. The final blow to the band was when Captain Beefheart signed Cooder for his Magic Band. Taj Mahal, the frontman of the group, was left alone at Columbia and he decided to start a solo career. He knew his new style of the blues was the way to go and sought a group of players with the same frame of mind.

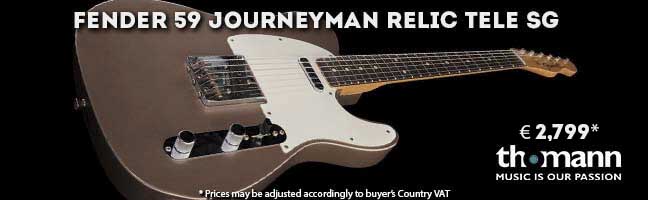

In 1967 he proved that his talent to get together with great guitarists was a gift when he inked Jesse Ed Davis, the second protagonist of the story, he was an Indian guitarist capable of making the sweetest sound on his Telecaster. Together with Gary Gilmour on bass, and Chuck Blackwell on drums, they became one of the most significant blues bands of the late 60s. Their debut was recorded in August 1967, and from the first notes on Leaving Trunk we can see, despite the strong roots of Mississippi blues , they were able to make it their own, either through the vocal inflections of their leader or the 1959 black Telecaster toploader solos by Davis, they brought electric blues closer to rock territory. But without a doubt, the deepest footprint left on this debut album was through another debut.

In 1968 Duane Allman was in bed at home recovering from falling off a horse, it was his birthday and his younger brother Gregg, who Duane blamed for the accident, came to visit and left him with two gifts that would give life to a new genre; a bottle of painkillers called Coricidin and the debut record of Taj Mahal. Two hours later Gregg got a call from his brother urging him to come at once. Upon arrival, he saw Duane with the empty bottle of pills on his finger, playing note for note the amazing slide guitar solo by Jesse Ed Davis on Statesboro Blues. We could say that the Allman Brothers and the whole rock world was born on that day.

But back to our main men - before the end of ‘68 they would release their second gem, The Natch’l Blues, possibly the best album of Mahal’s career. On it you will find songs like She Caught the Katy and Left Me a Mule to Ride, an original that years later the Blues Brothers would bring to fame, the brilliant Corinna, composed by Mahal and Davis, or Ain’t That a lot of Love, a song that would shine in an event that they should have shot them to the stardom, Rock & Roll Circus by the Rolling Stones.

And a few days before the record was released, on December 11 1968, Taj Mahal and his band took part in what seemed like one of the most important events of the year. A Rolling Stone TV special in which the only American band was his. The billboard was spectacular, with the Stones, The Who, Jethro Tull, Marianne Faithful and the Dirty Mac, a band put together for the occasion made up of John Lennon, Eric Clapton, Keith Richards and Mitch Mitchell. Mahal’s performance was brilliant and during the solo on Ain’t That a Lot of Love, Davis would win Clapton’s admiration for life, and would even invite him to record with him. However, unfortunately, the Stones decided not to play, as they thought The Who had surpassed them. But as Pete Townshend said, it wasn’t just The Who, “They were also surpassed by Taj Mahal, who as always, were extraordinary”. The whole constellation of British stars knew it, but it in their native country they were still unnoticed.

1969 saw one of the simplest double-albums of all times, Giant Step/De Ole Folks at Home, and more than being a double album, they were completely different from each other, the first with his band, with some great stuff like title song Six Days on The Road and Bacon Fat, with another great Davis solo, and the second just with him on his acoustic Mississippi Standard steel-body, a harmonica and his voice. The concept was clear, on the one hand was his own vision of electric blues, with a touch of R&B, country and folk, and on the other, pure bare-boned songs just as they sounded in the old days, with that sweet Delta aroma. Taj Mahal has always been a master in this sense, and has given some of the best concerts, as in An Evening of Acoustic Music, with just him and his audience.

Still, commercial success and stardom never came, Taj Mahal remained ‘the musician of musicians’. Giant Step was the quartet’s last record, although Davis returned to collaborate on a lovely version of Oh Susanna on his 4th record, Happy to be Just Like I Am, released in 1971. After that came new experiments and something close to reggae, influenced by his Caribbean roots, the jazz or a band with 6 tubas, where he would always leave his tremendous character and impeccable live presence. As for Jesse Ed Davis, he became one of the most sought-after session guitarists of the 70s, being known as the ‘ Telecaster man’, if anyone needed the sound of that guitar, Davis would be their first choice. You can enjoy his sound on records by Dylan, Lennon, George Harrison, Clapton, Jackson Browne, and a pair of wonders by Gene Clark. They all agree on his laconic description of his particular and gorgeous style: “ I only play the notes that sound good ”.

But let’s not leave without speaking of the last time they played together, it was at the Palomino Club in Hollywood in 1987. Davis had momentarily been able to rid himself of the drug addiction fantasies a couple of years earlier and had worked with Indian poet and activist John Trudell on a effort called A.K.A.Graffiti Man, that gave way to a band with the same name. Taj Mahal decided to seek out his old friend and just like that, the Palomino gig came up. It wasn’t a big club, yet there were many who didn’t want to miss it, people such as Dylan, Harrison, and John Fogerty who by the end of the evening were on stage performing the queen of all jam sessions, one number ending with Fogerty singing Proud Mary for the first time since the Creedence days, after Dylan jokingly said you better sing it or they’ll think it’s a Tina Turner song. It was an historic night that showed the enormous respect his mates and biggest names had for them. But, as so many times in his career, it didn’t do much more than make him proud. Davis returned to his old habits and died of an overdose a year later. As for Taj Mahal, he has kept playing on stages since then, releasing a record here and there. It may be that his name is not as well known as others, but rock royalty has always considered him as their own.