David Knopfler

The Quiet Sultan

By Matt White

I confess.

I’m a guitarist. A frustrated one.

Like so

many others I grew up listening to the greats - Clapton, Page, Santana,

Waters, Jansch - and yes, Hendrix, of course Hendrix. Also the great guitar

bands The Allman Brothers, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Yardbirds, Pink Floyd and,

naturally, Dire Straits. Not the extensive list but all had such unique sounds

- ones I happily murdered whilst trying to learn the instrument after school

- testing my parents and neighbours patience in the process.

It was

always apparent to me that I was never going to meet those dizzy heights so you

can imagine my pleasure to be invited down to David Knopfler's West Country

retreat for a conversation about his life, his approach to making music,

experiences of being a crucial member of one of those iconic groups and his

chosen path in the industry.

After a

pleasant drive through the idyllic Cornish countryside - I find myself sitting

across from a very approachable and affable man clearly very comfortable in his

own skin, and in reflective mood having recently released the part crowdfunded

album ‘Grace’- the 14th solo album in a varied and accomplished career.

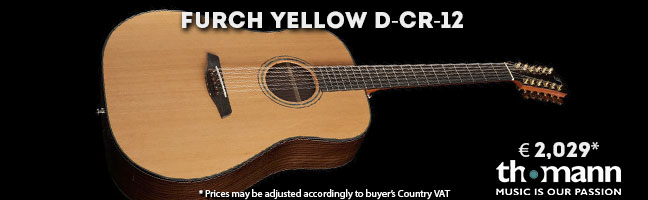

I also find

myself scanning his impressive range of electric, acoustic and bass guitars -

the pre-CBS Strat he used in Dire Straits is in prominent position, as well as

several beautiful Furch acoustic models. All a far cry from his early days when

at one point he tells me as a 15 year old he traded a heavy coat for a ‘Tommy

Steel’ guitar...in the dead of winter.

Later he

graduated to a Harmony Sovereign on the advice of Steve Phillips’ brother

(laterly of Notting Hillbillies fame) for £40 in 1975. Eventually he found

himself fixed on the Fender route with Telecaster and Stratocaster his main

guitars - he admits he never really got on with the flat neck of a Gibson -

but, illustrating his sincerity, he says that this is as much down to

serendipity as anything else.

After

starting out playing working men's clubs whilst still at school things quickly

escalated after forming Dire Straits with his elder brother Mark - but I get

the impression that even then the two siblings were treading separate paths as

guitarists and artists -

“I never

saw it as a horse race, I didn't think I was as good as I actually was, I did

have a bit of trouble hanging onto my brother's coat tails who had a more

than rare talent - but I was good - and I’m still learning.”

Four years

younger than his brother the sibling rivalry is clear - and like most siblings

the relationships are formed young - David relates that even in the earliest

years he would have to wait for his brother to go out so he could steal some

precious time on Mark’s red Höfner Supersolid.

David has

experience as an ex-social worker to draw upon and this appears to be core in

his grounding in the real world - something which must have been at odds with

the fame of a stadiumrock sized band admitting he felt ‘...alienated and lost

for the most part...’ but he always had his craft to fall back on - and even

after taking part in the other side of the business producing, setting up

record labels he knew that “...songwriting always brought me back to dry land.”

Which must have been comforting after admitting there was a time he couldn’t

walk down Oxford Street in London without people whispering behind him.

After the

major successes of the Straits early albums the brothers parted ways - for

David this was opportunity to concentrate on what he loved best - songwriting.

A path he

has followed ever since - the album Grace sounds like an artist who knows what

he’s best at and the company and gear the brings the best out of him. He’s

sitting in a room with a couple of 12-strings but tends to stick with 6

strings and simple arrangements that suit his style (He says he agrees with Steve Stills regarding 12-strings: “you spend half your life tuning and the

other half playing out of tune.” - Though I think that quote actually goes

back to Debussy about harp players - it still holds true!).

Grace is

recorded with musicians he has long standing relationships with - Harry

Bogdanovs, chief among them - and it’s clear he enjoys the collaborative

approach to making music and is wary of chasing faultless performance -

“seeking perfection is a recipe for trouble” - careful not to let that add to

the pitfalls of procrastination which he has seen occur to others in the

studio.

A

particular personal favorite on Grace is ‘Dawn Patrol’ a true boy's own story

of daring do - harking back to a boyhood fascination with WWI aircraft - and

inspired by memories of an earlier song penned and nearly forgotten some years

ago - though his refined simplicity comes back into focus now as he admits

looking back at old songs from 30 years ago and saying “...let’s forget that

middle eight - too many bloody jazz chords!”.

As

conversation turns to the question of style as a guitarist, its development

and refinement it’s clear he can see the process at hand in his own development

and it’s a lesson for us all, his retrospective view:

“You start

doing other peoples dance - they leave the footprints in the sand and you step

into those - eventually you start to leave your own - and you think you sound

like your influences - but there comes a point when you create something

that's uniquely you”

There’s

little hint of arrogance in his self-review - he’s still got his feet on the

ground and it shows - I ask if there’s any major difference in his stage

playing experience these days - it’s all about the encores:

“There was

a time when, if I got less than 6 encores, I be depressed - now if it’s more

than 2 I’m annoyed!”

It’s nice

to meet someone who’s been put through the fame wringer and come out the other

side not entirely unaffected, but with the sense of self assuredness that keeps

it in context - as he shows me some other guitars which would make a lot of

people jealous (including the Yamaha Bass which was used in Dire Straits and

never has had the string changed since 1977!) - he offers:

“...anyway,

a great guitarist will sound really good on a bad guitar - and an average

guitarist will sound really bad on a really good guitar and that’s the truth of

it.”

As he

noodles on a picking arpeggio arrangement on his Furch acoustic - illustrating

his approach to developing ideas (we both agree that unintentional mistakes are

often the catalyst to greater creativity), it’s clear he is content both in his

style and approach to songwriting, happy with his refined technique and in his

own words:

"I

just like to plough my own furrow - and be left in peace to do it.- It works

for me..."

Alarmingly,

having identified myself to him as a (frustrated) guitarist earlier he passes

me the Furch - and I too have a quick ‘noodle’ on the fretboard - I’m sure it

sounded pretty awful in such company but perhaps as if to underline the mark of

the man - he doesn’t point it out - and I don’t feel frustrated - just happy

to have enjoyed good company from someone who has been through it all and

remains positive and at peace with his chosen path.