Album Review: Paul McCartney And Wings - Band On The Run (1973)

By Sergio Ariza

Rediscovering the magic

By 1973 Paul McCartney had released four studio albums and several singles after the Beatles split up but few had taken him very seriously. The critics had taken a pop at him, and while his first two albums did not deserve the scorn, the next two were not up to the standards of a songwriter of his stature. On the other hand, in terms of sales, George Harrison was the most successful ex-Beatle, while John Lennon had earned critical respect thanks to his first two solo albums.

Moreover, there was a feeling that the bassist was responsible for the Fab Four's split, as he was the one who announced it and was alone against his three former bandmates who had aligned themselves with Allen Klein. But that year everything began to change, as Lennon, Harrison and Ringo Starr sued Klein and McCartney saw this as a moral victory, after years of confronting his three best friends. So he felt it was time to return to the big time and show everyone who Paul McCartney was, going so far as to tell his wife Linda "either I give up and cut my throat or I get my magic back".

Needless to say, if it had been a science fiction film, stars and colored lightning would have emanated from McCartney's body at that moment, but, as it was not a movie, what started to come out were some of the best songs of his solo career, some like, above all, the title song, but also Jet, Let Me Roll It, Bluebird and 1985 – that were on a par with his Beatles’ classics. With his ambition restored, McCartney began rehearsing the material with his band at the time, Wings, which consisted of his wife Linda on keyboards and backing vocals, Denny Laine on rhythm guitar, Henry McCullough on lead guitar and Denny Seiwell on drums. But shortly after McCullough left and Seiwell followed shortly after.

McCartney had decided to go to record in an exotic location and had chosen Lagos, Nigeria, without giving it much thought. When they arrived there they found a country that had just emerged from a civil war and was ruled by a military regime. To make matters worse, the studio was not in the best condition and there were neighborhoods that were better left unseen. Even so, the McCartneys did visit them, were robbed at knifepoint and lost several written lyrics and demo tapes of their songs. As if that wasn't enough, shortly after arriving Fela Kuti showed up at the studio in a fury, thinking that the white rock star was coming to do something that white music stars had been doing for a long time, culturally appropriating the music made by musicians of color, in this case his own, the irresistible 'afro-beat'. That was not true however, and when McCartney played several demos to Kuti to reassure him, Kuti saw that there was no such appropriation and the two became friends, with Kuti inviting McCartney and his wife to one of his performances at the Shrine in Lagos, which McCartney still recalls with emotion.

The thing is, Kuti needn't have worried because McCartney had decided ‘to look back without anger’ and seek inspiration from his later work with the Beatles. Now that the hatchet had been buried with the Liverpool band, McCartney decided to pick up where he left off: the glorious second side of Abbey Road. And if this Band On The Run is musically reminiscent of anything, it is the last album recorded by the Beatles and that second side on which McCartney linked several songs, by taking up themes from other songs and splicing them together. The best example is the title track, one of the best songs by McCartney and, if Maybe I'm Amazed didn't exist, the best of his solo career. The title was taken from a phrase of Harrison's at one of the Beatles' business meetings in 1969, another nod to their glorious past and proves that, despite being without lead guitarist and drummer, McCartney was perfect on his own (we should not forget that when Lennon said that Ringo wasn't even the best drummer in the Beatles, he must have been thinking of Paul).

From the moment the guitar riff that opened the song, and the album, with that synthesizer responding to it, it was clear that the magic had returned. But it's just the beginning of one of those mini-suites of songs that he's so skilled at putting together, with that first part giving way to a great rock piece and turning into one of those 'sing-alongs', with a slight country touch, that McCartney is so good at.

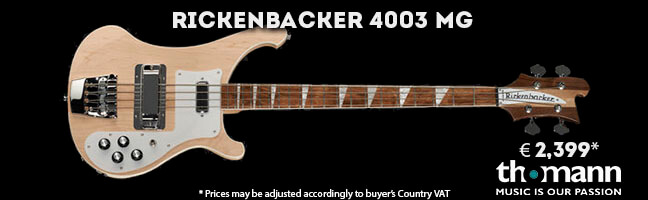

The rest of the first side was pure caviar, with the powerful Jet, halfway between power pop gem and irresistible glam rock, where McCartney puts an intense rhythm on his Rickenbacker 4001 bass and adds one of those trademark melodies for one of the most infectious songs - and that's saying something -, of his career. The beautiful Bluebird, a delicate bossa nova to put alongside his great acoustic tracks like Here, There And Everywhere or Blackbird, is followed by Mrs Vanderbild, with one of his trademark infectious bass lines, and closes with Let Me Roll It, the closest he has ever sounded to Lennon’s solo albums, with a cutting guitar riff and a raspy echoing voice (Of course, if Lennon could imitate him with Imagine, he could do the same).

The B-side was slightly below the level of the A-side, which is not to say it wasn't another marvel. Mamunia was a sort of Afro-soul track with a dazzling lightness, while No Words was a collaboration between McCartney and Laine. For its part, Picasso's Last Words (Drink to Me) is clear proof of McCartney's disarming songwriting facility; he wrote it in Jamaica in less than 20 minutes after actor Dustin Hoffman said to him that he didn't believe McCartney could write a song about "anything." Hoffman passed him the newspaper with the news of Pablo Picasso's death and the last words he had spoken "Drink to me, drink to my health. You know I can't drink anymore". In addition to winning a bet, the song serves to tie the album together with an excellent orchestral arrangement and brief appearances of two songs from side A, Jet and Mrs. Vanderbilt. The album closes with the spectacular Nineteen Hundred and Eighty-Five, over a strong piano, an adrenalized melody and a spectacular ending with a guitar solo included (courtesy of McCartney himself with, possibly, his Epiphone Casino or his transparent Dan Armstrong) and a full orchestra joining in. In the end McCartney goes back to the beginning and ends up returning to the Band On The Run theme.

He had succeeded; critics and the public fell in love with the album and Paul became ‘the most successful Beatle’. That same year came the definitive reconciliation with Lennon and things became rosy again for the most optimistic Beatle, but McCartney would never again feel that sting of ambition and competitiveness for the rest of his career. The great songs kept on coming, which is understandable for someone to whom melodies emerge with insulting ease, but no album would ever again reach the levels of this one or the underrated Ram...