The 10 best songs of Son House

By Sergio Ariza

The Mississippi Delta is one of the most mythical places for lovers of 20th century popular music, a place where legendary beings like Robert or Tommy Johnson ‘sold their souls to the Devil’. This is also where a number of black men shaped the most influential music of the 20th century, singing about their sorrows and tragedies, in a territory totally hostile to them - one where it was easier to end up hanging from a tree like a ‘strange fruit’ than to achieve success with your guitar in tow. One of the few figures who lived to tell those stories was Son House, and he was not just any character, but the most important of that early era, along with Charley Patton. From his primitive and emotional style of playing, legends such as Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters would drink. This former parish priest was one of the main figures when it came to preaching a new religion, that of the blues.

Preachin The Blues (1930)

In the 20's and 30's the distinction between religious music and ‘sinful music’ was very clearly defined in the black community: the former was used to praise God, the latter to talk about women and alcohol. The blues was seen as the Devil's music and those who practiced it were outsiders in the community. Son House spent the first years of his life preaching about God, even working as a pastor in a church but, we’re not sure if after going to a crossroads, at the age of 25, around 1927, he gave it all up, picked up a guitar and started preaching the blues. His previous faith gave his performances a strength that had never been seen before. House would sing rolling his eyes, as if he was in ecstasy - of course now those ecstasies were about other things, as can be appreciated in this Preachin The Blues that he recorded in his mythical first session, in 1930, and which contains lines like these: "Oh, I'd'a had religion, Lord, this very day but the womens and whiskey, well, they would not let me pray" or "Oh, I wish I had me a heaven of my own, Then I'd give all my women a long, long happy home". His subsequent followers responded ecstatically to his prayers.

Walkin Blues (1930)

Another of the songs he recorded in that mythical first session (on May 28, 1930 in Grafton, Wisconsin, for Paramount Records) was this Walkin Blues in which we can appreciate the enormous impact that Son House had on Robert Johnson. The young Johnson followed House and his partner Willie Brown to all the bars and joints where they played, trying to play with them… but he did not have their level. Of course, after disappearing for a while, Johnson returned with a much more perfected style than that of his masters, who could not believe the change. In House's primitive style you can hear the blues without any sweetening; it is pure and raw. Moreover, Johnson was not his only disciple, since we can also see in this Walkin Blues the roots of Muddy Waters' (I Feel Like) Going Home; the first song recorded by the giant of electric blues for the Chess label.

Levee Camp Blues (1941)

After the death of his friend, and rival, Charley Patton in 1934, Son House first retired from music and then began working as a tractor driver on various plantations, but in 1941 Alan Lomax sought him out to record for the Library of Congress. This specifically took place in August 1941 at Klack's Store, Mississippi, and House was accompanied by his friend Willie Brown on guitar, Fiddlin' Joe Martin on mandolin, and Leroy Williams on harmonica. If they had been plugged in this would be a sound very close to the Chicago blues that Muddy Waters and Howlin' Wolf would make famous.

Country Farm Blues (1942)

Delighted with the recordings, Lomax returned the following year to re-record House. On July 17, 1942, among other new tracks, he recorded Country Farm Blues in which House made clear what went on in the plantations, "Down South, when you do anything, that's wrong, They'll sure put you down on the country farm (...) Put you under a man they call "Captain Jack", He" sure write his name up and down your back." The Lomax recordings could not have been more significant, because afterwards House moved to New York and left the world of music for the next two decades.

Death Letter Blues (1965)

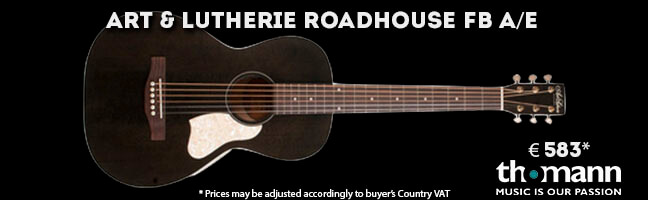

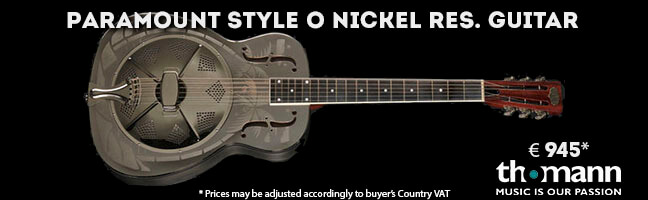

But, after more than 20 years away from music and guitar, House was rediscovered in 1964. The voice was still there but he had not practiced guitar and couldn't remember his own songs, so Columbia's John Hammond decided to contract 22-year-old Alan Wilson to ‘teach Son House how to play like Son House’. Soon they recorded an album together - it may not be as important as their 1930 recordings, but that album, released in 1965, may be the best of Son House's career. Not for nothing does it contain this monumental track, Death Letter, in which it can be appreciated that House has mastered his instrument to perfection again, achieving some of the best slide moments with his National Duolian resonator of the 30's. His imprint would also spread over new generations when Wilson formed Canned Heat or, years later, when the White Stripes recovered this song, with the same primitive caveman spirit (but plugged and distorted) in their De Stijl.

Pearline (1965)

Another marvel from that 1965 album (which, by the way, was called The Legendary Son House: Father of the Folk Blues), is this Pearline, in which Son House's mastery of the slide is once again proven. The glorious sound of the slide sliding down the metal box sounds as menacing as a rattlesnake about to strike. House proved that at 63 years old he had found his inspiration again; no matter how crude his technique, few can rival the emotion his playing conveys.

Grinnin’ In Your Face (1965)

The power of the blues, when interpreted by someone who really feels it, is such that a voice and a few claps are enough to make any heart feel the pain of the one who is singing it. House's voice is husky and expressive but every inflection is there and you can see how it comes out in a totally natural way, inherited generation after generation, a universal lament capable of touching anyone, no matter what culture they come from. This song experienced a new wave of popularity when Jack White brought it to light in the famous documentary It Might Get Loud.

Downhearted Blues (1965)

Recorded in the same sessions as The Legendary Son House: Father of the Folk Blues, Son House takes this blues number popularized by the great Bessie Smith and turns it into another demonstration of expressiveness and strength, as well as formulating like few others the fundamentals of the blues: "I woke up this morning, feeling sick and bad, thinking of the good times I once had..."

How To Treat A Man (1968)

There's a bit of a mess with this song, on YouTube it appears under two different names, My Black Mama and I Wish I Had My Whole Heart In My Hand (the first verse of the song), but the name of the song was How To Treat A Man. Son House performed it in 1968 with Buddy Guy accompanying him on guitar, and it is spectacular to see two totally different generations united for one prodigious song. Guy is playing here and there but he is more interested in seeing how the master brings out those incredible sounds on his resonator with the slide, learning first hand from the same source as his godfather Muddy Waters. House went on to record it on Liberty's John The Revelator LP in 1970, but the most exciting version is the one that reunites House and Guy, even though it is sadly brief and doesn't have the best of sounds.

Son's Blues (1969)

An anthological recording; 20 minutes of pure bluesy delight. House roars with explosive force, his voice comes from his guts and his guitar strings crackle in a slow and fiery performance. This track was recorded in September 1969 at the artist's home by blues fanatic Steve Lobb. House alternates throaty roars and beautiful falsetto and in doing so creates a deeply mournful and incendiary sound. At nearly 70 years old, the master was still preaching the blues with the same fervor as ever.