Duane Allman’s 10 Best Solos

By Sergio Ariza

Duane Allman is the most legendary figure of southern rock; the pioneer and builder of the genre. He was a born leader who had already become the best known regional figure in the area, as Lynyrd Skynyrd or Tom Petty might testify, but who decided to return the sound of his land - the land that saw the birth of blues and rock & roll - to the top of the charts. Together with a wonderful group of musicians who believed in him almost as a messianic figure, Duane knew how to get gold out of the instrument and become one of the most important guitarists in history… up there with Clapton or anyone. In less than two years he took his band from the worst clubs in the South to the biggest stadiums in the country; but just when he was beginning to reap the rewards and glimpse massive success he died in a motorcycle accident. It was the end of the man but the birth of the myth, which is understandable if we consider that in less than three years he left a body of work that places him among the greatest rock guitarists in history, as these 10 wonders that we have selected here prove.

Blue Sky (1971)

I'm not exaggerating if I say that Why Does Love Got To Be So Sad? is one of my five all-time favorite solos; so how come some other one beat it? Well, because before he died at the age of 24 in a freaking car accident, Duane decided to say goodbye in style by giving his partner and friend Dickey Betts the most beautiful solo of all time. Betts had written Blue Sky for his girlfriend and brought it to the band to be sung by Gregg Allman, but it was Duane who told him: "man, this is your song and it sounds like you, you need to sing it". Of course, that wasn't the best gift he gave his partner, performing the all-time favorite guitar solo of this writer. Using his beloved major scale, Duane demonstrates that he has the same melodic skill with the guitar as McCartney, by writing unforgettable melodies. On this song he creates a solo that sticks in your mind and can be sung with the same ease. It is also a further demonstration that Duane was an absolutely prodigious guitarist without the use of the slide. Nor is the author of the song left behind, who, after harmonizing with Duane, throws himself into the wild with another magnificent solo; but that first solo by Duane is something else, perfection made music. It is also Duane's last studio recording before his death, and it demonstrates the enormous loss that his death represented.

Why Does Love Got To Be So Sad? (1970)

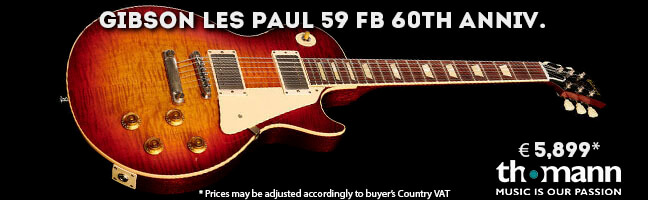

Beyond Layla, Clapton and Duane’s great moment at the guitar on that album which they shared recording is Why Does Love Got To Be So Sad? The song begins with Clapton on the rhythm guitar and singing, heart in his mouth, for his love for his best friend's wife. Duane is then unleashed on lead guitar, answering every inflection of Clapton's voice, with some of the best notes of his career. His Les Paul is in a state of grace, from 1:18 when he begins his first solo, it is absolutely brutal and at dizzying speed, then at 1:40 he is joined by Clapton in a totally glorious moment with… both of them doing solos at the same time! Amazingly, the miracle is that the best is yet to come as the voice returns while Duane continues to spit out absolutely incredible notes, the tempo drops imperceptibly, the solo becomes more and more melodic, then at three minutes Clapton returns and one of the most memorable moments in the history of rock music occurs, as two of the best guitarists enter into one of the most incredible guitar conversations in history. Here you can listen to the Les Paul and the Stratocaster demonstrating their iconic power as the tempo continues to drop and as if communicating with telepathy they begin to respond to each other with incredible fluidity; it is pure guitar magic.

Mountain Jam (1971)

This is a monument and the song that best reflects what the Allman Brothers could be live. Usually, the long half-hour jams performed by a rock band are boring exercises in self-indulgence with little to say, but the Allmans had such a rapport with each other that they could take a jam based on a Donovan song to heights unimaginable for most jams. That was because it was a group made by and for live performance, but also because Duane Allman is one of the few rock musicians capable of withstanding comparisons to improvisational giants like John Coltrane and Miles Davis, whose Kind Of Blue was his strict musical diet in the Fillmore East years. This song would simply be a good 'jam', as most times the band got on stage, if it weren't for what happens from 22 minutes on when Duane starts with his second solo, first at the same time as Dickey Betts, and then from 23 minutes and 43 seconds on his own, what Duane achieves then is one of the peaks of expressiveness of the electric guitar. The furious beginning taking full advantage of the slide is incredible, then he calms down, as if the storm had passed and he begins to play one of the most exciting solos in history, the intensity increases again and the band begins to let itself be carried away by Duane's strength, as if he were transporting them all, then he puts the brakes back on and begins to play the melody of Will The Circle Be Unbroken, with Betts doing some arpeggios. Here we are already entering guitar Paradise, with an absolutely heavenly tone, giving some of the most beautiful notes of his career, as if he were a preacher reaching ecstasy...

Hey Jude (Wilson Pickett) (1968)

After getting fed up with his label's impositions with his first project, Hour Glass, Duane left California pretty pissed off and took the band to Alabama to record a pure blues demo at Muscle Shoals Studios. The tape didn’t do much but the owner of the studio, Rick Hall, was impressed with the hippie guitarist and decided to call him to the studio for a session with Wilson Pickett. Duane did not hesitate, he was a fan of the soul singer and also could make extra money, so he went there with a guitar that was not yet his legendary Les Paul but a Stratocaster with a Fuzz Face connected to a Fender Twin Reverb. When he got there Pickett did not have anything ready for the session, so Duane proposed recording the Beatles’ Hey Jude. Everyone was shocked, as the Fab Four had just released it and it was still on its way to number one in the charts, but Pickett trusted the guy who was as strange as he was in the conservative and reactionary Alabama of the time. So they started recording and Pickett took it to his world, with an organ that shouted gospel at all four walls. Duane was giving brushstrokes here and there… but he had already prepared the moment when he would give free rein to all his explosiveness; just as the final twist was beginning, Pickett screams out loud and turns on all the alarm bells. Pickett's cry then unleashes true madness, and both Allman and the singer bring out their best in a finale in which Hall (with great success), buries in the mix the "Na, na, na, na" of the chorus girls and leaves all the weight with Duane's guitar and Pickett's prodigious voice. The album, of course, became a great success on both sides of the Atlantic, and made a stunned Eric Clapton considered it the best solo he had ever heard. He didn't know that he would soon be playing with Duane on his great masterpiece. For his part, Jimmy Johnson, the official session guitarist of Muscle Shoals, said of Duane's solo that it was "the beginning of Southern rock.”

Layla (1970)

This is the most important song of Eric Clapton's career but we can't forget Duane Allman's enormous contribution to it. Starting with the famous riff, which Allman took from the first verse sung by Albert King on As The Years Go Passing By. Here he pulled incredible sounds from his Les Paul, using the slide and taking it beyond the 23rd fret. And then there's the famous piano coda where Allman uses his famous 'bird call' sounds to give it its most distinctive sound.

Whipping Post (Live At Fillmore East) (1971)

Here Duane shines on several occasions and in different ways. First there is the first solo, from two minutes, which is pure strength and speed, played several times with intensity, raising and lowering the tempo at will, then it is Dickey Betts who stands out with an anthological solo; one of the most beautiful ever made. Gregg returns with the slowed down chorus and then Duane shows that he is the most inventive guitarist of his generation with a great final coda for the song.

In Memory Of Elizabeth Reed (Live At Fillmore East) (1971)

Listen here to the interaction of the two guitarists, especially how Duane and Dickey Betts complement and harmonize with each other, in a wonderful combination of spirits that, at times, reminds one of Miles Davis (Betts) playing with John Coltrane (Allman). What made them great was that neither sought to eclipse the other but simply to dialogue. The song is by Betts and has the most jazzy sound in the band, but listen to Duane's solo after the solo of his brother's Hammond B3 to understand why no one doubted that he was the leader of the band. It's a fiery and incendiary solo from which sparks fly on every note; in the end one wonders how it is possible that that blessed Gibson Les Paul of 59 remains whole after such a solo.

Anyday (1970)

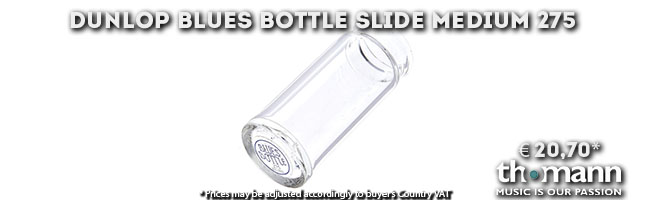

I have to admit, I could have filled this special with songs from Layla & Other Assorted Love Songs, one of my favorite albums of all time. I think it's the best album of Clapton's career and a lot of that is down to his interaction with Duane, who he brought into the band without hesitation the very day he met him. These two were made for each other; at this time Clapton had already passed to his Stratocaster, specifically to his famous 'Brownie', and Allman already had one of his famous Les Pauls, but the curious thing is that both came from opposite sides - Clapton had been responsible for popularizing the Les Paul in rock with his 'Beano' from the Bluesbreakers and Allman had made a name for himself playing a Strat in the Muscle Shoals’ sessions, for people like Wilson Pickett and Aretha Franklin. Even so, both had found the instrument that would define them for the rest of their career (in Duane's case sadly short) and are at the top of their game, their styles and tone are totally personal and know how to complement each other perfectly, with Clapton leaving plenty of room for Duane's brilliance, while he sings, and returns the confidence by playing like a real demon. Anyday is one of the best examples on the album, one of the most rocking moments, with both using the slide. Clapton gives it his all, with his heart broken and his veins full of heroin, but it is Duane who takes care of the solo, first with his fingers and then adding his slide, which in his case was a Coricidin bottle top. And then there's the finale in which he transforms Clapton's pleas into heavenly music, masterfully coloring all the singer's emotion.

You Don't Love Me (Live At Fillmore East) (1971)

Another 15 minutes of guitar glory taken from the best album of the Allman Brothers' career, the essential Live At The Fillmore East. Here Duane gives again a demonstration of versatility, first, after about two minutes, he unleashes a violent and wild solo, while the second begins after about six minutes and a half, and in it he mixes everything, first quick runs that could have been made by Jimmy Page; then the whole band stops and leaves Duane alone to take his B. B. King inside and deliver a solo in which he demonstrates that he can play the blues at the level of the best.

Don’t Keep Me Wonderin (1970)

This song appeared on the Allman Brothers' fantastic second album, Idlewild South. Written by his younger brother, who also sang it, Don't Keep Me Wonderin was the perfect vehicle for Duane to demonstrate his mastery of the slide. The curious thing is that by this time, February 1970, the older Allman had been playing with the slide for less than two years but, even so, he was already taking it to never before reached levels of expressiveness and feeling.