The Humble Master of Technology

by Vicente Mateu

Back 50

years ago, the future Commander of the Order of the British Empire was dragging

along half dead from hunger in search of non-existent adventures in France and

Spain. He had barely turned 20 years old as the '60s started drawing to a

close. His dream ended when he returned home, but only so a new one could

begin. Pink Floyd was already taking its first baby steps and had a serious

problem with its guitarist, who mixed inspired genius with madness in equal

measure. It was not rare for him to be unable to finish their concerts. The

solution was to hire a childhood friend, one of his six-string mentors from the

streets, to cover for those crisis moments. That friend was David Gilmour

(Cambridge, 6 March 1946), en route to becoming a legend; Syd Barrett,

unfortunately, was on the verge of forming part of it.

The short

circuit in Barrett's mind, in the end a cruel twist of fate, changed the life

of that young musician from Cambridge and in turn marked the lives of millions

of people spread over several generations who would also learn to soar through

the neck of a guitar. The journey began in 1963 with his first band, Jokers

Wild, and still isn't over, even with Pink Floyd occupying a place of honour alongside

the Beatles and Stones.

And whether

Roger Waters likes it or not, in the eyes of history and the fans, Gilmour's

guitar playing buried him beneath the bricks of The Wall they built up between

them. And with the contributions of Mason and Wright as well, as everyone

knows. Pink Floyd was the magical summation of a group of musicians with

exceptional talent and vision, the children of psychedelia and strict British

education converted into superstars who wound up being torn apart by ego

conflicts. They needed each other, but they could not stand one another, a

classic situation in that era among the major groups of the rock Olympus.

The balancing

act barely lasted a decade. Like it or not, Pink Floyd was over by the early

80s. Freed of the onerous presence of the bassist, Gilmour finally had absolute

control of the group, or more accurately the brand until, after a pair of

albums recorded in fits and starts, he was really the only one left and the

whole thing stopped making sense. It was time to take off and fly solo from the

riverboat studio on the Thames that had become his headquarters.

A new David

Gilmour was born, a multi-faceted artist and multi-millionaire benefactor of

non-profit organizations. His status as a guitar virtuoso and innovator in the

rock world was no longer enough and he decided to expand his skills by becoming

a world-class producer and sound engineer. A facet into which he has thrown

himself more than in his own recording career and which has almost given him

greater satisfaction. Kate Bush is a special case in point, elevated to fame as

the result of her wonderful vocal trills, enhanced by the great technical

knowledge of her mentor. Along the way, he managed to revive what was left of

Syd Barrett in a joint project that included a tribute.

His

personal career was on hold for all practical purposes. Half-a-dozen albums in

over three decades with a gap of over 20 years between the first two –David Gilmour in 1978 and About Face in 1984- and the rest of his

solo output. In 2006, he returned with On

an Island; two years later with the bombastic live album in Gdansk recorded

with a symphony orchestra, and, in 2010, with Metallic Spheres, a joint experiment with The Orb, the electronic heirs

of Pink Floyd.

Five

years later, he released Rattle that

Lock in the wake of the success created by The Endless River in 2014, a new album released under the Pink

Floyd marque and produced from outtakes recorded during the band's final

years, when Rick Wright was still alive. He swears that is the final chapter,

the last album by the legendary band. Both albums show that Gilmour is in fine

form.

However,

since the '90s, his guitar never stopped being heard as a special guest of B.B.

King, The Who and Supertramp... just part of a long list of artists that also

included Bob Dylan. It was an era of creative silence interspersed with

numerous appearances, like the short series of acoustic concerts in London that

he received rave reviews for in 2002.

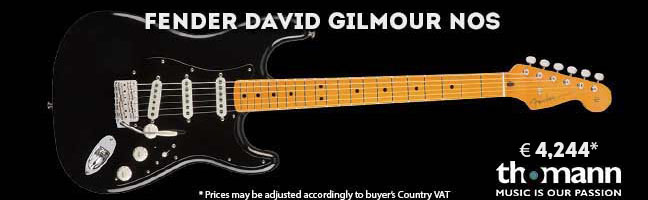

His

intensive use of available technology enabled Gilmour to create his own style

by constantly exploring the limits of his instrument, sustaining each note

endlessly without lifting his foot from the effects pedals or releasing the

vibrato bar of his Fender; undoubtedly the preferred brand of a musician who

has certainly tried out every make of guitar at some point in his career.

The humble

Gilmour says his complex set-up helps him to conceal his technical shortcomings

in a world –he forgot to add this point- where many people confuse speed with

virtuosity. You don't measure the power and passion in his playing by the

number of notes. One note was enough for him to stop time in the '70s and LSD

took care of the rest.

Gilmour was

also much more than a great guitarist: he knew how to get the most out of his

voice and played a number of other instruments quite well, from drums to sax.

He had everything under control ... except Roger Waters.

At this

point in his career and with more than 70 years under his belt, Gilmour is going

through that phase of technology disconnection common to guitarists of his age

bracket who spent their lives plugged in to an amplifier. Many of the gadgets

that blanketed the floors of studios with cables just a few decades ago –you

can find detailed accounts of which ones he used on almost every song on the

Internet- don't exist now except to prove how difficult life was without

computers. And computers don't hold any secrets for him anyway. It is time to

search for new challenges.

He has enlisted

a world-class collaborator for this new stage, none other than Phil Manzanera,

an old friend who turned into something much more than a producer over the last

few albums. Manzanera is the perfect complement to be able to continue enjoying

the guitar of Commander David Gilmour, a legend who still has yet to write the final

chapter of his musical career. Or, better still, give the final lesson.

(Images: ©CordonPress)