Ground zero of electric blues

By Sergio Ariza

Perhaps T-Bone Walker is remembered more for his famous disciples than his own music, but anyone who plays an electric guitar is indebted to him, as he was the first one to plug the instrument in to play and sing the blues, thus creating, electric blues. His Stormy Monday pushed B.B.King into getting an electric guitar but, besides that, the show he put on when he played, usually holding it horizontally against his body, and other times behind his back, and playing with his teeth, influenced Chuck Berry and Jimi Hendrix who always mentioned him as one of their biggest idols.

Aaron Thibeaux Walker was born May 28, 1910 in Linden, Texas the same year as Howlin’ Wolf and one year before Robert Johnson. Both his parents were musicians, so he started to play any instrument with strings at a young age, from the banjo to the mandolin, and on to the violin, ukulele and the guitar. His first idols were Lonnie Johnson and Leroy Carr, but as a Texan blues musician his greatest benefit was to have received lessons from the minister of that school, the very own Blind Lemon Jefferson. The blind guitarist was known by the family and each time he was in his neighbourhood, young Walker would accompany and guide him through the city while Blind Lemon played and sang. In return he taught him all he could, and the kid absorbed it all like a sponge.

At 17 or 18 years of age he got his first big professional opportunity travelling in one of those bizarre road shows in which somebody plays doctor and tries to sell an all-cure snake oil, in this case something called Big B Tonic. Walker’s job was to attract a crowd by playing the banjo and ukulele. He did it very well and got hooked on the performances. When he played in public he switched to the guitar because it was easier to hear, and it was what he preferred to play at home. He was getting a following in the area and together with his stepfather, the man who gave him his first guitar, they played at all the juke joints around, where the made money for playing the songs that were requested, as if they were a traveling ‘jukebox’.

He recorded for the first time in 1929, singing and playing the guitar, together with a piano in Trinity River Blues and Wichita Blues, in the recordings he is credited as Oak Cliff T-Bone, Oak Cliff was where he was living at the time, and T-Bone comes from the way people pronounced his middle name Thibeaux, but Walker took it with affection. Soon after he won a contest on the radio which allowed him to play a couple of weeks with the Cab Calloway orchestra, who after this experience, put some of his songs in their set list and earned him the nickname ‘Cab Calloway of the South’.

In 1933 he began playing and singing with the Lawson Brooks orchestra, playing regularly in Oklahoma where he met a young guitar prodigy Charlie Christian, who at 17 had just left school to devote himself to music. Walker was so impressed that he started playing with him and with his brother Edward on piano, in the streets. In their gigs Charlie played guitar and T-Bone the bass, and then they would switch instruments and even danced together for a bit. In a few years they would become, respectively, fathers of the electric jazz and blues guitar. Walker never tired in his admiration for Christian, a musician who he gave his first chance when after getting work in New York, he gave him his spot in Brooks’ orchestra.

In 1935 in New York he saw Les Paul for the 1st time with an electric guitar, and decided to get one, but it would be on the other coast where he would put it to good use in the city of L.A. where he started playing in clubs in the Central Avenue area. He found a place to live and a real job as a member of The Hite orchestra, but just as a singer, it was at night when he would scorch his guitar and let loose his love of the blues. His big break would come in 1942 when he was signed by the Café Rhumboogie of Chicago, the city which had become the northern blues mecca. The Rhumboogie gave him to his first so-called record label, and Walker cut some singles there, things like I’m Still in Love With You, Mean Old World, and T-Bone Boogie. His popularity allowed him to leave the Hite orchestra and form his own band, which had 10 players at the start and settled with just seven. Their style was sharp yet profoundly influenced by jazz, mainly because of their ‘dixieland’ origins in New Orleans, he was unstoppable as a singer as well, yet with a style closer to Big Band singers like Jimmy Rushing than the deep wild ones of people like Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters.

In 1947 he signed with Black & White where he laid his most popular track, Call It Stormy Monday (But Tuesday Is Just As Bad), known simply as Stormy Monday. This would be the song that prompted B.B. King, and hundreds of other guitarists (among them Clarence ‘Gatemouth’ Brown, Lowell Fulson and Albert King), to get an electric guitar, thanks to the excellent work of Walker and his 6-string. King himself used to talk about it saying, “the first line he plays, those exciting first notes, the first sound that comes from his guitar and the attitude in his voice were fascinating”. Over time he would become one of the most famous bluesmen of all time, getting covers from Bobby ‘Blue’ Band, Etta James and the Allman Brothers.

Many consider this period as the most important of his career, while with Black & White he put out Inspiration Blues, T-Bone Shuffle, Go Back to the One You Love, Bobby Sax Blues, and West Side Baby. With his unique, soft and melodic phrasing Walker made his guitar the focal point and not just a tool. His style was unique and live was even better, Walker devoured the stage, moving up and down, and displaying all kinds of tricks like playing behind his back or with his teeth. His trademark was playing with the guitar horizontal to his body. Many took note of his careful stage presence.

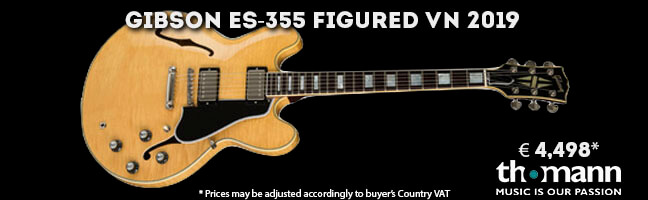

From 1950-1954 he recorded on the Imperial label, another of the most outstanding stages of his career, now out with his band of jump blues from L.A. or with the inimitable Dave Bartholomew, Walker was back producing another string of classics such as Glamour Girl, The Hustle Is On, Tell Me What’s the Reason, High Society, Cold Cold Feeling and the unstoppable Strollin’ With Bones, which served as an inspiration to Chuck Berry on some of his ‘licks’ in Johnny B. Goode. He signed with Atlantic Records in 1955 taking him back to Chicago in a session where he cut classics like Papa Ain’t Salty or the fundamental Why Not, based on the classic Walking By Myself by Jimmy Rogers, who was at that session with him. In December of ‘56 and in ‘57 he returned to record in L.A. along with his nephew R.S. Rankin Jr., who they also called T-Bone Walker Jr., and the jazz legend Barney Kessel. In these sessions they would recreate some Walker classics like Stormy Monday and Mean Old World, and the sound of his guitar was absolutely brilliant. If until that moment he mainly used a Gibson ES-250, in these sessions he began to play the guitar he would play for the rest of his life, a Gibson ES-5, although there were times when he would use a Barry Kessel model or a Gibson ES-335.

In 1959 Atlantic would gather all these sessions on one of the most important records in his career, T-Bone Blues, whose album cover shows him playing the guitar behind his back. The 60s were not the best time for him, the blues was getting more spartan at the time and he started having physical troubles. Still, there were good things like his recordings with Memphis Slim and his appearance in London in 1966 with the group of Jazz at the Philharmonic that brought people together like Dizzy Gillespie, Teddy Wilson, Louis Bellson, Clark Terry, Coleman Hawkins, Zoots Sims, Jimmy Moody and Benny Carter; in addition to outstanding albums like I Want a Little Girl, released in 1968.

In 1971 he received a Grammy and a year later, at the Jazz Festival in Montreux, Chuck Berry brought him up to sing with him on Everyday I Have the Blues. At one point he gives him a 335 to play, something the old dude who created rock & roll just as we know it wouldn’t have done with anyone else but his hero. Walker would die 3 years later, on March 16, 1975.

He may not be remembered with the same reverence as Berry or King but you can’t have a minimum of passion for the electric blues and not stop at the work of a man considered to be its ground zero, being the first one who joined two of the things that we like most in the world, the blues and the electric guitar.