A decent man

By Paul Rigg

Carl Perkins found fame writing Blue Suede Shoes and taking it to the very top of the charts;

played alongside Elvis Presley, Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, Johnny Cash, Bob Dylan and the Beatles;

and was named as one of Rolling Stone’s top 100 guitarists of all time, but his

roots were as humble as can be imagined, and he carried them with him all of

his life.

Almost

incredibly, Carl Lee Perkins (9 April 1932 – 19 January 1998) grew up

picking cotton in America’s deep south because he was part of the only white

family working on the plantation near Tiptonville, Tennessee, just a few miles

from the Mississippi River.

Friendships

with black people were strongly discouraged but that did not stop Perkins

having a black best friend by the name of Charlie, even though they had to

catch different buses to go to school and sit separately whenever they had the

chance to see a show.

At six

Perkins would pick cotton for up to 14 hours a day and listen to his fellow

pickers singing in the fields. “There would sometimes be 40 or 50 people strung

out across the cotton rows and I would hear an old black man who I loved so

much, John Westbrook, start humming

[hums a deep bluesy sound], and about eight or 10 rows down sister Juanita

would sing ‘ooohhh, yeh’ [sings a high blues lament]”, he says. “Little chill-bumps

would start up on this little boy’s arm and I said [to myself]: ‘oooo-hee,

they’re gonna sing!’”

Religion

was always important to Perkins. The music he heard sung in the fields was

complemented by the southern gospel sung by white folk in his local church.

“God put me in that situation for a reason and […] that was for me to dig deep

in my soul and create my music,” he says. His father would constantly play

country music on their old battery radio – because there was no electricity in

their shack – but, for Perkins, “it was the environment in which I was raised

that made my country music just a little bit different.” That ‘little bit of

difference’ was to later become known as ‘Rockabilly’, which Perkins described

as “not music you just sit and listen to; if you don’t move then something is

gonna break”.

Perkins loved the guitar from an early age, but at

that time workers would earn just 50 cents a day, and so his father made him one from a cigar box and a broomstick. Although hardly anyone believed in him,

Perkins felt that the guitar could be his ticket out

of the cotton fields, and when he listened to the radio he could “picture

rhinestones, cadillacs and big houses, and those dreams filled my little soul.”

Shortly afterwards a neighbour on hard

times offered to sell the family a beaten up Gene Autry model guitar with spent strings.

Perkins’ father bought it for Carl for a couple of dollars [plus a chicken, according to one of Perkins’ interviews], and it was

his old cotton picking colleague, ‘Uncle Westbrook’, who became prominent in

his life once again to teach him how to play: "Get down close to it,” the

old man said. “You can feel it travel down the strangs, come through your head

and down to your soul where you live. You can feel it. Let it vibrate."

Perkins’ mother wanted him to play in

church but he never earned anything there and he desperately wanted some money

to renew his strings, which he literally had to tie back together each time one

broke.

Those were tough

times, but Perkins never regretted any of it, because he had what he believed

was most important: “When I look back I had a mum and a dad and two brothers

that loved me,” he says in his interview with Tom Snyder.

In fact, Perkins’ brothers were key in

his life in many ways. At around 13 he and his brother Jay,

who was two years older, and Clayton,

who was two years younger, formed a band and started to play honky tonk. “People

would come to listen to our music that other country bands were doing, but we

were doing it in another gear,” he recalled years later.

The brothers first earnt money from

customers’ tips playing once a week at the Cotton

Boll Tavern on Highway 45, near Jackson, in 1946. As drinks were also part

of the deal, it was here that Perkins first got a taste for alcohol that was to

take him to the brink of destruction years later. Bar fights also featured

regularly and it was not unusual for a night to end with one of the brothers

throwing himself into the audience to ‘sort things out’; though Perkins later

said that he always preferred to try to calm things by simply cranking the

volume up on his guitar.

Perkins taught his older brother chords

so that he could play lead, and encouraged his younger brother to play bass to

round off the sound. As the 1940s ended, the Perkins brothers had become an

established act in the area.

At this time Perkins penned a song

called Let Me Take You to the Movie, Magg,

celebrating a girl he met in Lake County, which later helped him get his first recording

contract with Sun Records in

Memphis. Perkins explains that in 1954 he heard a

DJ called Bob Neil on the radio say

‘I’ve got a brand new boy here by the name of Elvis Presley singing Blue Moon of Kentucky’, when he had been

playing the same song for at least three years. “In my soul it was pretty close kin to what I had been struggling with,

and I set my sights on Memphis and went down, saw Elvis, and pleaded for an

audition.” Movie Magg was

recorded shortly afterwards and in February 1955 Perkins heard himself on the

radio for the first time.

It was the start of a close collaboration and

friendship with Presley. “I think God

sent him as a messenger, he came with a new type of music and way of moving,”

Perkins says. “He didn’t know what he was

doing at first: I heard him say he was very nervous and his legs would start

shaking and he didn’t want the audience to know, so he’d throw them out – he’s

history; he gave America what it needed at the time.”

And Perkins gave Presley what he needed with the song Blue Suede Shoes – but not before

Perkins had had a hit with it first. The inspiration came from Perkins watching

a boy and girl jitterbug near the stage during one of his shows. They caught

his attention because they were dancing so well and, as the song ended, “he

said to her in a good style tone ‘don’t step on my suedes!’ and she said ‘Oh, I’m

sorry’. Coincidentally Johnny Cash had already suggested to Perkins that Blue Suede Shoes might make a good title

for a song, and in that moment something sparked in his mind. “I couldn’t sleep

that night,” he says, “I went down the concrete steps and started writing.” The

noise he made woke his wife who came down the stairs to complain that he was

going to wake the children up.

In fact

Perkins was about to wake the whole world up, as soon his song sold over a

million and rocketed to the top of the US Billboard charts. Presley’s advisers

encouraged him to immediately record and release the song himself, but the man

from Memphis did not want to spoil his friend’s moment and so he waited until

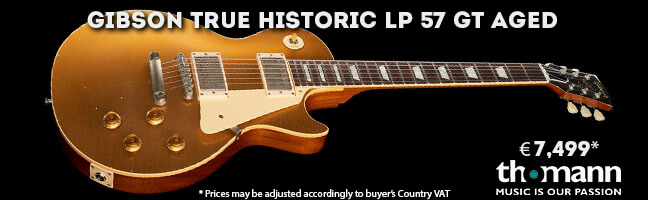

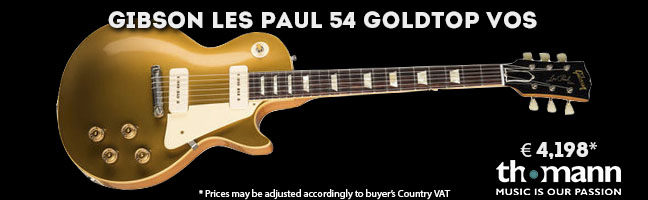

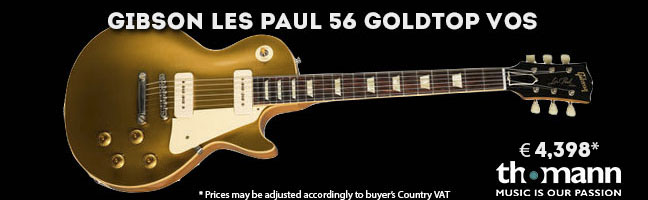

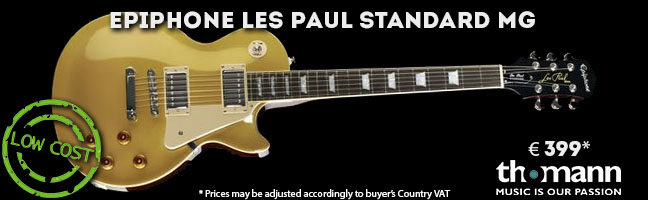

Perkins’ song, which he recorded on a 1955 Les Paul Gold Top, was on the way down the charts before he released his own famous version.

Even the B side, Honey

Don’t, was later to be covered by the Beatles.

At this

moment Perkins star was nearing its peak, and he was scheduled to sing his

biggest hit on Perry Como's famous TV programme, and on Ed Sullivan’s show shortly after. However, on his way to Como’s

studio the car he was travelling in was involved in a terrible accident,

killing a driver, and leaving Perkins and his brother close to death. He was

about to be the first Rockabilly artist ever to appear on network televison;

but it was not to be.

As Perkins

lay in hospital, doubts flooded his brain: “I talked to the Lord and said ‘you

gave it to me, are you now going to take it away? Is this it? Am I gonna die? Is

my brother gonna die? Am I going back where I started?”

While

Perkins convalesced, Presley became a household name. When Perkins was finally

able to record the song on the Perry Como show, it was possible to see on the

recording how badly the accident had affected the band. Clayton had not been so

injured but his brothers both look gaunt, and Jay in particular looks

incredibly stiff because he is still wearing a barely disguised neck brace. “I knew he wasn’t well,” says Perkins, “even

when we did the Perry Como show with him in his brace and his twisted smile you

would never know that he was in so much pain. But he wanted his brother Carl to

sound like he did on the record, and that is a love you cannot buy [tears

stream down Perkins’ face]. I lost a jewel of a brother when Jay [died in 1958].”

In the same

year as his brother’s death, Carl Perkins left Sun Studios because he was

‘feeling overlooked’ but it was a decision he lived to regret. “I shouldn’t

have ever left Sun…” he says in one interview, “I got mixed up in big studios

with people who didn’t understand Rockabilly.” Often producers wouldn’t even

let him play guitar on his own records and his despair, along with his dependence

on the bottle, grew.

However,

even through the dark years, Perkins status always remained high among

musicians.

In May 1964, although

initially reluctant because

he feared his star had faded, Perkins successfully toured the UK with Chuck Berry.

In 1968, Perkins then toured with Johnny Cash;

however it was during this time that he returned to rock bottom. During a

show in California he saw

"four or five of me in the mirror" during a four-day drinking binge.

Later he fell to his knees on the beach and said "Lord, ... I'm gonna

throw this bottle. I'm gonna show you that I believe in you.” Cash, who had

experienced similar problems, supported him on his quest.

Before Bob

Dylan became famous he recorded Perkins’ Rockabilly

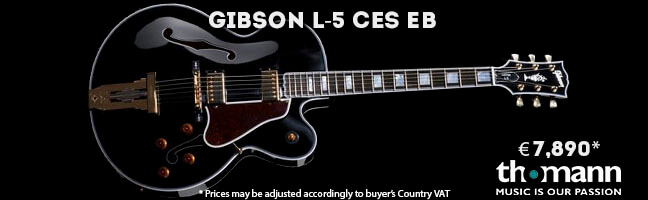

classic Matchbox, on which Perkins had

shone with his Gibson ES-5 Switchmaster. Dylan later went to the studio in New York City

where Perkins was rehearsing in 1968 and they played guitar together. In one

example of the affection that they had for each other, Dylan had written the

song Champaign, Illinois, but didn’t

know how to finish it; so Perkins did it for him and Dylan gave it to him for

his album, On Top.

In

1981 Perkins recorded Get It with Paul McCartney, which appeared on the album Tug of War, and later the Beatle showed his enormous

admiration for the Rockabilly legend on a video documentary about his life. A

further highlight at the end of his career was a TV special shot in London with

Eric Clapton, Ringo Starr, Dave Edmunds, and George Harrison. Perkins was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1987.

Perkins last big concert in 1997 was for

charity, and one of his final great benevolent acts was to establish the Carl Perkins Child

Abuse Centre in Tennesssee.

Married to

the same women for over 45 years, he came to accept ‘his level’. “It’s not what

you lose in life but what you are left with [that’s important],” he says. “If I

had had another Blue Suede Shoes it might

have made me not care about people, but I do, and that makes me happy.” In one

of his last interviews, he reflected on what was most important to him: “I’d just

like the world to know that I tried to be a decent man,” he says.