The Humble Guitar Hero

By Paul Rigg

British-born Peter Frampton (22 April 1950) is a

guitarist, singer-songwriter and all-time rock legend.

Frampton began his career at 14 in The Preachers working with Bill Wyman of the Rolling

Stones; he went to school (and later toured) with David Bowie; and then formed Humble Pie before going solo and

becoming a global superstar, following the release of Frampton

Comes Alive! Since then he has worked with many top acts, released a

dozen albums, and in 2007 won a Grammy for Best Pop Instrumental Album, Fingerprints.

Guitars Exchange

catches up with Frampton early morning in mid-May 2018 while he is in Los

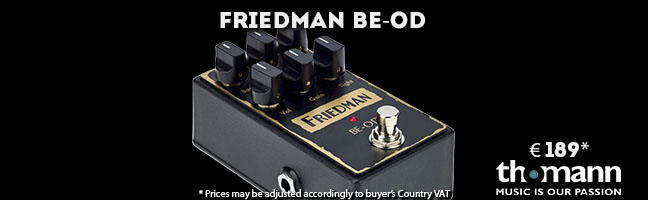

Angeles, where he is visiting friends. As he bought a number of pedals the day

before (an OCD, a Friedman ‘Dirty Shirley’ and a Boss digital delay DD500 –

which he says “is the mother of all delays”) he has been jamming away, and

plans to continue once our interview is over.

But for now, his guitar is on his bed

next to him, he has a coffee in his hand, and he is keen to talk about his

incredible career, his difficulties dealing with fame, and the future of

guitars in the week that Gibson filed for bankruptcy.

GE:

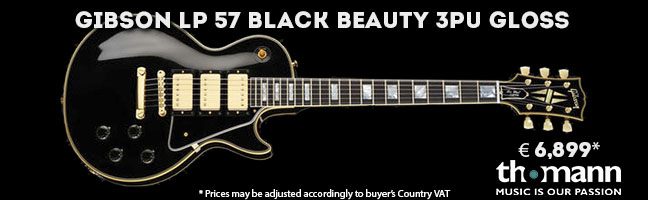

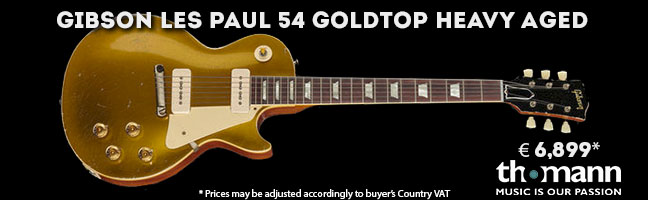

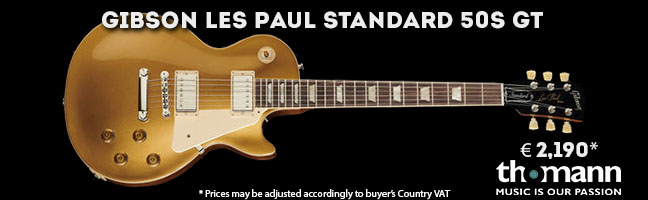

Were you shocked to hear the news about Gibson going bust?

PF: We’ve been hearing the rumours for

some time. I know nothing about the business side of it at all and that is not

my forte, but I don’t think Gibson will ever disappear, it is a heritage

company and I think it will be saved. That’s my hope. It is too historic to

disappear.

GE:

Does it say something about the future of guitar music?

PF: It goes up and down – one year it’s

keyboards, then it’s flutes, and then it’s guitars again; maybe it will find a

level one day where it will be constant, I can’t say. But the guitar is such a

desirable instrument, once you know you can play a song from beginning to end

you are hooked. As I go around the world I continue to notice young guitarists

coming out of the woodwork. I recently met a young girl of 11, her name is Joy,

in a school of rock in Winnipeg, Canada, and she was so passionate about her

guitar. We both started when we were seven years old, and she had the same

passion as I did. So they are still out there.

GE:

Going back to the start of your career, what was your first guitar?

PF: My first instrument was a banjolele

that my grandfather gave me through my dad, which is what George Formby used. It was tuned like a ukulele but it was the only

thing I could get my finger’s around the neck of when I was seven years

old. But within the year I asked for

what was called a ‘plectrum guitar’ – it had no other name. I don’t have the

original now because, of course, you had to part exchange your first one for

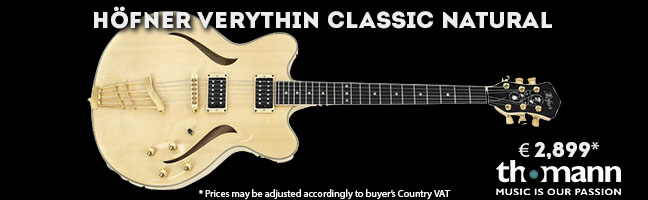

your second in those days. My second one was a Höfner Club 60; I loved that

guitar. That was my first real electric.

GE:

You started The Herd when you were only 16 and you were part of the Mod

movement; what was it like to be involved in the ‘swinging London’ scene at

that age?

PF: Well it was pretty surreal for me

except that I didn’t really know what surreal was; I just experienced it on a

daily basis. My first big recording session was when I was 14, in a band called

The Preachers. Bill Wyman was linked

with us because the drummer Tony Chapman,

who was a friend of mine, was the original drummer of the Stones, before Charlie [Watts], and he introduced Bill

to the Stones, so when Tony was no longer in the band Bill felt indebted to us.

He said ‘when you get a band together I will take you into a studio, be the

producer and help manage’, so I then became friends with Bill very young. So

when I was 15 I was going out to all these after-hours clubs with him (laughs)

and there I was all wide-eyed drinking my Coke or Pepsi with Brian Jones or Paul McCartney there. Bill basically

discovered me, and The Preachers ended up being produced by Glyn Johns because he was doing the

Stones, so it was like starting at the top on my first serious session. It was

at the peak of 1966, I was 16, and I had been going up to town since 1964; much

earlier than I should have been going up there. It was unforgettable.

GE:

I have heard that in the last months of the Small Faces, when Steve

Marriott decided to leave the

band, the other three asked if you wanted to be his replacement; is that true?

PF: Yes. It’s funny because Steve, rest

in peace, and I were on the phone talking about names and he threw about half a

dozen names at me and I said ‘Humble Pie, that’s the one, I love that’. So I’d

just hung up from Steve and Ronnie Lane,

dear Ronnie, called me and said ‘can the three of us come round and see you?’ So

they came around and did ask me and my only thought was ‘we could all have been

in the same band’, which was sad for me because ever since I first saw the

Small Faces on Ready Steady Go!

playing live ‘What’cha Gonna Do About It?’

I said ‘I want to be in a band with that guy’ [Marriott]. He was something else,

he was such a talent, and I’m just thrilled that I got to work with him for so

long.

GE:

When Humble Pie began to move to a more hard rock sound with Rockin' The

Fillmore it has been suggested that you felt you had to leave the band; did you

resent that?

PF: No I didn’t in fact. There is some

misconstruing here. I actually came up with some of the heavier riffs before

Humble Pie, like ‘I Don’t Need No Doctor’

and ‘Stone Cold Fever’ to name just two,

so you can’t really say that heavy rock wasn’t my thing: it was, I loved it. It

is just that our direction had got narrowed and that’s all we were doing,

because that is what the audience wanted. We were sort of gravitating towards

making the live show as powerful as possible; especially as we were going on

and opening for acts in 10,000 seater venues, we wanted to be remembered. So we

hit the ground running every show and it got more and more electric, which I

loved, there was nothing wrong with that at all, it was phenomenal, but the

more acoustic side of Humble Pie was being reduced, and I wanted to be able to

run the gamut as opposed to doing just one kind of thing. I think I proved that

on Wind of Change, my first solo

album, which ran the gamut from acoustic guitar to Billy Preston and full rocking.

GE:

Did you meet the legendary pedal steel player Pete Drake while both of you were helping George Harrison record ‘All Things Must Pass’?

PF: Yes.

GE:

I understand he was instrumental in introducing you to the now-famous talk box.

What was the thing that most captivated you about that effect?

PF: Do you remember Radio Luxembourg? Do you remember the call sign? They were 208

on the dial, and they had the call sign ‘Fabulous 208’ [Frampton makes a

distorted 208 sound] and it was done on something very similar to a talk box,

so when I used to listen to Radio Luxembourg, which had the only good music on,

from 7 till 10 I think, that sound just got me. So when Pete Drake sat down in

front of me in Abbey Road studios, with a metal box and a little pipe in his

mouth, and the pedal steel started singing to us, me and George were just

watching and thinking ‘what the hell is he doing?’; we were gobsmacked, our

jaws dropped, and I just went in my head ‘there it is, that’s the sound I’ve

been looking for all these years’.

Americans don’t make that link between

the talk box and Radio Luxembourg, but it closed a circle for me incredibly

quickly and I said to him ‘where did you get that?’ And Pete told me that he’d

made it himself. Later Rose Drake, Pete’s wife, got a call from Joe Walsh who’d heard about this

thing and he said ‘would it be possible to borrow Pete Drake’s talk box, I’ve

got this track I want to do’ and that was Rocky

Mountain Way, which I still think is the ultimate talk box solo.

Later Joe said to Bob Heil, a dear friend who makes microphones and PAs, ‘Bob, can

you make me one of these but louder’ and Bob said ‘yes I think I can’ and that

became the very first Heil talk box. Bob gave me one as a christmas present,

probably in 1973. I took it and locked myself in a rehearsal room for probably

a week and I came out talking with it. I used it for the first time on the

Frampton record, which is the studio version of Show Me The Way, but then introduced it into the stage act for a

part of Do You Feel, to amazement at

the effect it had on the audience.

The funny thing was that we were opening

for Joe Walsh (laughs), this was before the live album, and so poor Joe – I’d

already used the talk box before he comes on – I’m not sure how well that went

down at the time but we laugh about it now, so...

GE:

Did you have a feeling before the album was recorded live that it was going to

be so special?

PF: Well the first time I used it on

stage it just knocked me back - the whole band were knocked back - it was like

the entire audience moved 12 inches closer to the stage en masse, it was

magnetic, people just had no idea what was going on. The thing is my sense of

humour is British, obviously, self-deprecation always wins, and that’s the way

I am, I never take myself seriously. It’s a funny sound and if anything, I’m

making fun of myself in many ways by making these computer-like noises, that

no-one had really heard at that time. So it was massively effective from the

first time I used it onwards. It still has the same effect but I think it’s

more now because the songs are ingrained in people’s memories. But youngsters

come in - the audiences get younger and younger, thank goodness - and I still

see the amazement on their faces. 150 bucks it cost me and it has sold me over

17 million records so far so…

GE:

Many artists fall apart in the face of that kind of success; how did it affect

you?

PF: I fell apart! (laughs). Totally!

(laughs).

I thought that I had it figured: I’d been

produced by a Rolling Stone, I’d been in The Herd and Humble Pie, I’d been on Top

of the Pops, I know all about this successs business, you know, you

just roll with it and everything’s fine, and then Frampton Comes Alive! comes out and I… I turned into chopped

liver. I became this demanded thing and I turned into an entity rather than me,

and I lost myself for a while. But I defy anyone not to need some time to deal

with that, it was pretty phenomenal. But I’m a survivor, I’m very pugnacious:

if you knock me down I’ll come right back up again, and I’ll come back

stronger. I think I get that from my mother and father who were both very

positive figures in my life; I was very lucky I had such good parents.

GE:

Thanks for that; now for a change of direction! I’d like to say a series of

names and ask you for one word or a first memory that comes to mind:

Jerry

Lee Lewis?

Oh my goodness, I got to play with Jerry

Lee Lewis on a session with Albert Lee

and Rory Gallagher – I can’t believe

it. It was the beginning for me of being a session player – that I was going to

do more of, later, as I left Humble Pie. That was when I started to be asked by

friends to play on their records. You know I was petrified, the man’s middle

name is ‘killer’, so I was a little intimidated, but he was very nice and welcomed

everybody in. It was a bit like going to the Co-op and taking your number and

then waiting for someone to say ‘ok number 19, you’re up!’ and there I am with

Albert and Rory; it was just amazing!

Ringo

Starr?

One of my dearest friends, and a

phenomenal drummer. People sometimes put it differently to that but I am a huge

Ringo fan because nobody else could have played on those Beatles tracks and

made them sound so unique; plus his feel is completely different from anybody

else. I wrote my very first song with him last year and next week I am going to

write another with him, as I am in LA right now. I told him: ‘I’ve got your

horse and I’ve been polishing the sword, so I’m bringing it around Sir Ringo,

I’m going to make sure you’ve got your armour on okay’ (laughs).

Barry

Gibb?

Lovely man, wonderful writer and singer,

very funny, and someone who is very serious and passionate about what he does.

Mike McCready?

First of all he is a huge Humble Pie fan!

(laughs) He’s such a lovely character; the Pearl Jammers are just like one big

happy family. I’ve played with Mike and Matt

[Cameron, of Soundgarden] on Black Hole Sun, and one other that we

did together, which is a thrill. Mike does so much for charities - youngsters

and Crohn’s disease, he has been the poster boy for them, he’s done so much good.

Touring

with ‘Yes’?

Which one? (laughs) I’ve toured with them

all! There’s Yes, there’s No-Yes and there’s Yes-No. In fact I’m going to

dinner with Trevor Rabin next week because

they’re going out with the Jon Anderson

version of Yes very soon. I have always been a Steve Howe fan, even before he was

in the band, and Chris [Squire] I

remember from the Marquee from a band called The Syn, because The Herd would play there as well. We all go back

a long time. Alan White of course is

one of my all-time favourite drummers. And Bill

Bruford. They have always had tremendous players.

GE:

Turning now to guitar questions, two years ago you recorded an album called

Acoustic Classics, in the ‘Unplugged’ style. What was your gear for that album?

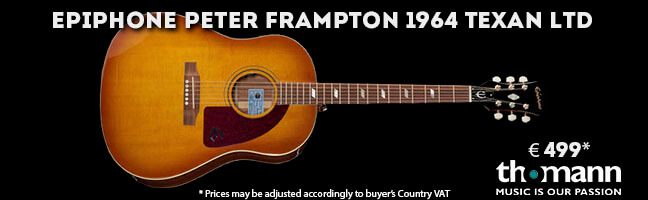

PF: Guitar wise I have a couple of Peter

Frampton D-42 Martins, which I use in different tunings. I had my original

Epiphone Texan that I played with Humble Pie and wrote all my songs on up until

about 1980, I used a refurbished version of that, and a Dupont, a French Django

type guitar, phenomenal, which I got straight from France. Then I also have an

old Tacoma Chief cutaway acoustic.

We mic’d it with two Neumann U67s that

had been modified to have a little more high end in them, and those were used

as a stereo pair about two feet away from me, and then two stereo mics up close.

No limiting was done on recording so if I sang at the same time I would use

another Neumann U47, depending on whether I was singing live or just playing

the track first. I allowed myself an acoustic solo, and then on Do You Feel that was the only one where

I played an acoustic bass, so there was no electric guitar on there except of

course for the talk box. I ummed and I

ahhed about it because it was going out of the

realm of what it was but I said ‘it won’t be the same if I don’t use it’, so I

did; but that was the only electric part on the whole record.

GE:

Which guitar players have you listened to in the past few weeks?

PF: I still listen to the old guys. Django Reinhardt, Kenny Burrell, Wes Montgomery, George

Benson, the early and the later George Benson - he was 16 when he played

with Jack McDuff, an unbelievable

player - that’s my jazz side; and then I’ve been listening to all the Kings and T-Bone Walker because I’m going to be recording a few blues tracks,

because we started doing Freddie King’s version of the ‘Same Old Blues’ and it is going down so

well live. My band and I are very excited about it.

GE: Finally, what advice would

you give to a guitarist just starting out?

PF: Do what I did! I just listened to as

many different guitar players from as many genres as I could that appealed to

me, and I tried to learn note for note what they were doing. In the old days

you got the album and slowed it down from 33rpm to 16rpm so it would be an

octave lower but half as fast; but nowadays there are all these wonderful apps

that slow things down. I still do it, because that’s how you learn, thinking:

‘how the hell does he do that?’ My fingers aren’t as long as I would like,

certain things are not as easy for me, but I’ve learnt to work around it and

learn my own style. And that’s what young guitarists should be striving for.

Listen to many guitarists – and other instruments; I learnt Little Walter harmonica solos, for

example, because he was trying to play like a guitar through a distorted amp

with his harmonica and it came out sounding like Little Walter – anything for a

challenge, make your brain and your fingers go where they haven’t been before

when you are practising. One day when you’ve done enough of that you wake up

and you play and you think ‘that’s me’; you play it your way. That happened to

me during Humble Pie – I wasn’t playing straight blues or straight jazz but I

felt ‘wow, this is me now’. It’s a wonderful feeling when you make your own

style.

The interview closes with Frampton

mentioning a popular Youtube video featuring his walkabout with David Bowie in

Madrid, when they were ‘looking for a beer’, and he says that video, in

particular, is one that warms his heart. Then we briefly chat about his upcoming

tour of the US with Steve Miller, and he explains that

whenever they play together it always goes down really well.

Despite being a rock legend and guitar

hero to many, the man from Humble Pie remains self-effacing, gracious and very

entertaining; no mean achievement in an industry full of one-upmanship and egos.

I thank him on behalf of Guitars Exchange and he replies: “you’re very welcome,

we can do it again whenever you wish.” And there he is; a gentleman to the

last.