His Magnum Opus

By Tom MacIntosh

Tubular Bells, the mesmerising masterpiece by Mike Oldfield was released 45 years ago (May 25, 1973), and was indeed ahead of its time and still stands as a monumental opus of progressive rock. In fact the album was meant to be called Opus 1, but was later reconsidered.

It was recorded at the Manor Studios in Shipton-on-Cherwell, Oxfordshire, an old squash court turned into a residential recording studio by a young entrepreneur named Richard Branson and his partner Simon Draper, plus the music production team of Tom Newman and Simon Heyworth. Oldfield was just 19 at the time and was amazingly adept at playing several instruments, including pianos, harpsichords, mellotrons, guitars, and various orchestral percussion instruments, the the list would soon grow.

It was 1973 and progressive rock was already in full bloom with acts such as Jethro Tull (A Passion Play), Yes (Tales from a Topographic Ocean), and Pink Floyd (Dark Side of the Moon), so it was quite surprising that this young fellow, Mike Oldfield, could make any impact at all on the scene. A year earlier, he had been busy making demos of his arrangements, and when they were ready to go, he shopped them around to 15 or 20 labels to no avail; nobody was interested in music without any vocals. He had heard that the Soviet Union was paying musicians to play live music and was looking for the number to the Russian embassy when Simon Draper called and invited him for dinner at Branson’s houseboat in London. He brought his demos and they were eagerly received and it was agreed that he take a week and use the Manor to lay it all down on vinyl. It was the first album released by Branson’s new label Virgin Records, and made them into a force in the recording business..

How to describe the music is challenging enough without killing it in the dissecting process. Suffice to say that every man and his dog will recognise the opening piano phrase which was used to open the Oscar winning film The Exorcist. According to Newman, the music was a series of sketches, not really intended to be what was the final result. He explains the poignancy of the music, “it was romantic, it was full of pain and anger...I saw the whole range of human emotions in that little demo tape”. Oldfield asked for several instruments to be brought to him during the recording sessions: guitars, keyboards, and several percussion pieces. The tubular bells were something he saw that was being removed from the studio after a John Cale session, so he asked if they could leave them behind for possible use on his recording.

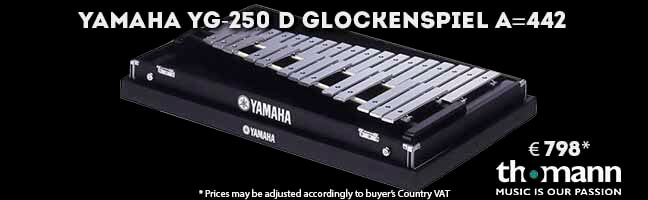

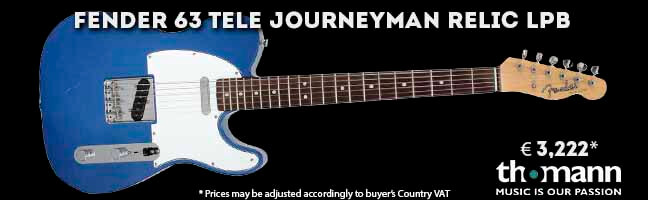

The signature opening piano line is then joined by a the organ and glockenspiel, repeating several variations of the signature start. The mood floats from serene to something sinister then more upbeat and raw, featuring a ‘conversation’ between organs and rock guitar licks. He used his trusty blonde ‘66 Fender Telecaster for the entire recording. Time shifts are all over the first 20 minute side, from 4/4 to ⅞ and drifts into some bluesy guitar riffs over the polyrhythmic bassline until the end. Vivian Stanshall who plays the part of M.C., introduces each instrument in turn at the finale section, until the harrowing tubular bells chime in, which gave Oldfield the name of his record.

The lineup for the record included: John Field/flutes, Lindsay Cooper/string basses, Steve Broughton/drums, Mundy Ellis and Sally Oldfield/chorus, Nasal Choir/chorus 1, Manor Choir/chorus 2, Vivian Stanshall/voice on ‘Master of Ceremonies’ and Sailor’s Hornpipe commentary. And of course Oldfield, who played the following: grand piano, organs (Farfisa, Lowrey, Hammond), glockenspiel, mandolin, bass, acoustic, electric, fuzz, Spanish and speed guitars, honky tonk piano (a tribute to his grandmother who also played), assorted percussion, flageolet, tubular bells, concert tympani, guitars sounding like bagpipes, choir conductor and co-producer.

Side 2 was highlighted by the ‘caveman’ bit, the only part where Broughton’s drums are heard, and the shouting sequence was due to the annoyance Oldfield felt for Branson’s insistence on having vocals on the album. “You want lyrics!, I’ll give you lyrics!” he shouted then stomped off and emptied a bottle of Jameson’s whiskey down his neck, and “screamed his voice off for 10 minutes” into the microphone. The engineer later sped up the recording which dropped the voice pitch, and gave us what was named in the credits, the “Piltdown Man”. It is certainly surreal, and some thought it was in bad taste, but it served to underline the peaceful yet explosive intent, making it dangerous yet enchanting.

As they say in the business, “it’s easy to make a record, the hard part is selling it”, but that’s just what Branson was born for. He arranged for the band to perform at the Queen Elizabeth Hall concert. Oldfield was dead set against it because he thought the hundreds of overlayed dubbings forged in the studio could not possibly be done in a live setting. On the way to the show, in a panic attack, he told Branson he wasn’t going to do it, so Branson offered him a deal, he offered to give him the keys to his Bentley if he went through with it. Mike accepted the offer and history was made.

Tubular Bells sold 2,630,000 copies in the U.K. and sat on top of the U.K. charts for months!

It would go on to sell more than 16 million copies worldwide, and won a Grammy in 1974 for Best Musical Composition. The iconic artwork on the album cover was done by Trevor Key who got his inspiration after seeing the damage Oldfield had done to the tubular bells during the recording. The ‘bent bell’ has been linked to Oldfield ever since, and appears on all the subsequent Tubular Bell sequels.

Even though Oldfield hated the instant mega-star status, it set him up handsomely in the commercial sense, and he became one of the few revered musician/composers of all time.