Harrison, (In)Complete Circle of Life

by Alberto D. Prieto

George Harrison, undoubtedly, belongs to the immaterial world of the soul. It is

impossible that during his presence of 58 years as a mortal being—the way “we” mere

mortals knew him—was his purest state of being.

At the very least, it could not have been for him because he never reached the

level of perfection he constantly sought. Or at least that is what he always

thought. Or showed us. Harrison was

always unsatisfied, his Beatle persona—a bit of a loner and a consummate

perfectionist, yet someone who held the secret to creating some of the most

perfect rock melodies—not to

mention, was the preferred companion to many aspiring stars of the star system, who with him or with him

as -human, musical or both-lever reached the nirvana of the covers, the

groupies and the money.

Bearing that

in mind, George Harrison—a loner yet

never a soloist—lived in a state of constant contradiction between what he felt

and what he made us feel. Internally, he knew—whether this is inaccurate or

not, only the gods may know—that he was imperfect, incomplete. A melancholic Harrison asked

for love and peace on earth, in his songs: divine

principles that closed his circle. Outwardly, each foray into song

writing Harrison came up with always

had an unmistakable stamp; be it poppy, rock, bluesy or

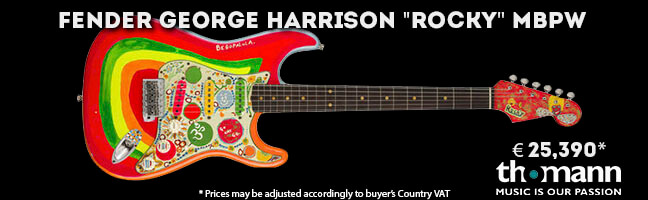

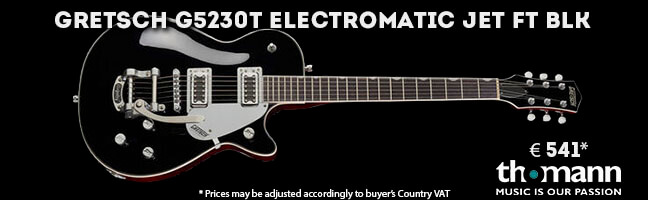

incomprehensible, he never betrayed himself, nor the six strings of his Gretsch—or the 26 strings of his sitar— they

all formed part of his eternal

sound staff that drew full circle, each providing

a new, slight tweak to his soul.

Harrison, George.

Beatle, friend. Betrayed, womanizer unlikely. Biased smile;

depth look. If his guitar weeped, his voice moaned and if not, the opposite. Even

on good days, he lacked the arms to calm all the

arpeggios and fine tune them in to chords.

To inherit a

famous surname can open and shut doors for you, just like how being a beatle can introduce you to glory Olympus

but obscures you as an individual. Even as a musician. Added to all that

immense luck dodging, George Harrison added a truly persistent effort to be who

he was: a guy who hid his vital need to support his heart whilst amongst the

company of others under the guise of a mystical aesthetic lonely soul in front

of open doors. Crossing Harrison’s

threshold was a risk that not even he himself ever committed. Until he finally gave

in, delving into his inner riffs and

released the hidden musician in him, full of inventive harmonies, which oozed

creativity and exuded truth from every pore of his guitars. Six, twelve

chords—or the 18 or 26 of the sitar—acoustic in the demos, electric in the studio

and eclectic in his adventures, there is no better love song toward a woman

than 'While my Guitar Gently Weeps' and

there exists no better version, honestly, than the one he recorded himself, sat

against the hard floor of his mansion in Friar

Park, no matter how much it was later “perfected “ by his great companions

and Clapton sublimated in its final

commercial form. Perhaps because by then his alleged bosom buddy had already

begun to his plan to snatch the beautiful Patty

Boid and the song is a pledge to leave in his selfish slow-hand the exchange of partners.

Hidden behind

those beautiful tremolos and bridges of the

enormous headstocks of his old Gretsch Guitars

from the 50’s from Rickenbacker ‑which

was brought to him custom-made-, taking advantage of their beautiful pickguards

to release his anxiety, Harrison thought

of the ostracism that McCartney and Lennon only further exasperated, learning

to show only the most sophisticated splinters of his constant inconstancy. With

his shifty eyes, he channelled the styling of Chuck Berry and his Gibson

ES355 and from the Epiphone of Chet Atkins his technique, the

experimentation of Townshend and his

Les Paul, from Clapton and his Strat came

the anxiety of glory and deepness from the Martin

Dreadnought of Dylan... and yet

at the same time, he drew inspiration from none. Perhaps it was due to the hindu influence in his life, since he

had been visiting India since 1965, or

perhaps his interest in the integration of symphonic

harmonies and echo and, without

a doubt, there was another key ingredient: the perfect blending of his voice with the sound that drew from his guitars plugged into his Vox... all of this, whatever the

reasons, created not only a unique style; rather unparalleled

and impossible to recreate, present in every beat and measure that left

a lasting mark on the Beatles or

himself in his later career.

Still with the

warm dead body of his beatle persona,

All things must pass (1970) is a

smooth orgy of ukuleles, wah-wahs and wailing guitars, an emotional outburst of

a melancholy spiral, absolutely proud. Creative. A double

album, which shows the errors of the

ways of the dancing couple

who led the fab four for maintaining,

in order to further their own glory, this pearl of compositional artistry in an

unjust and counterproductive ostracism. Harrison

bore his best work up until the very last moment—providing all the parts of a possible

pregnancy just before the divorce of the most famous band of all time—perfectly

capable of completing one of the best albums of the Beatles. Gems such as Isn't

it a Pity or Art of Dying showed

that to release the accumulation of genius from years

ago of little affection—all he needed was a little caress. And with the first triple LP in the history of rock to

reach Number One on the American and British charts before any of his three

former band mates, it showed what he already suspected of himself: complete

with Phil Spector, Klaus Voormann or

Bob Dylan, in accompaniment, his incompleteness

could turn into a compositional capacity

comparable to the best accompaniment.

Almost always,

George used to buy guitars like the

ones Lennon previously owned. Once

he began his solo career, the multidisciplinary artist (musician, producer,

instrumentalist, film promoter) and multifaceted man (religious, benefactor,

businessman, drug addict) gave flight to new interests, and each step drew him

away from any interest for show business;

his records included more experimentation and musically, less concessions to

commercial. Of course, his vast wealth and recurring royalties allowed this timeless journey into the depths of his soul

and only occasionally would some project drew him for a little while from

his chosen melodic melancholy that became his rain hat to wear during his rainy

life.

In fact, back

in the year ‘82 when he joined some friends

for a party in the studio to work on a fresh and fun new album, the carrier

pigeon of the charts brought him a message, reminding him that this was out of his

character. The album Gone Troppo, which

arrived on the scene only a year after the rather successful Somewhere in England only cracked the

American charts at 108 and didn’t

even make it to the English charts. Amongst other vinyl joke tracks of great

merit include I Really Love You, (self) hidden

tributes such as Mystical one and

glorious ones such as Circles... purely

White Album.

Hereinafter

the worshiper of the ukulele, sitar and

Krishna withdrew from the music scene and only visited for pleasure. Throughout

his musical life, George Harrison

understood the need to be supplemented with four arms and four heads Vishnu, creator

of the world and first on the

path of reincarnation towards

perfection, and his

forays between cables and guitars were limited to ponder the significance of

the past with the 'Fab Four' on

several tracks of Cloud nine, his last successful album, or begun to work alongside

four other friends: Tom Petty, Jeff Lyne, Bob Dylan and Roy Orbison in the unfinished project

known as the Travelling Willburys.

There remains

the consolation of thinking that despite what he always felt, his death in 2001 was the death of a complete human

being in his ultimate state of being... Yet we bore witness to 58 years of a

legacy of perfection from which to draw lessons. The irresistible attraction of

his virtue deifying the guitar, which completed such great genius, suggests so.

However, only the gods know.