The despair and the beauty

By Paul Rigg

Guitarist and

songwriter Nick Drake is a cult folk

hero who is revered as both a guitarist and songwriter among people of all

generations. Every year scores of people from all over the world gather in Warwickshire’s

Tanworth-in-Arden, the town where he spent a large part of his life, to pay tribute.

In 2000 a TV commerical made his track Pink

Moon, recorded in 1972, a top five hit on Amazon sales list, his songs were

used in films, and all three of his albums made Rolling Stone magazine’s ‘top

500 albums of all time’ list. Drake is the subject of a number of biographies

and dozens of articles and documentaries about his work. Because of his innovations

in guitar playing and his widespread influence on major acts like R.E.M., The Cure,

John Martyn, Elton John and Beth Orton,

there are many who consider him a genius.

On the night of 24

November 1974, however, Drake was in an entirely different space. It was common

for him go downstairs to eat a bowl of cornflakes in the small hours, when

usually one of his family would wake to talk with him, but on that night he

walked straight past his parent’s bedroom door and no-one heard him.

Due to his

depression, which had seen him hospitalized, his family had taken to hiding aspirins

and other pills but, as his father relates it, it hadn’t been felt necessary to

do that with his anti-depressants.

Drake was in a

particularly dark place. His sister says that he felt ‘he had no more songs.’ His

last sessions, his producer Joe Boyd says, were “agonizing.”

He had told his mother “everything I have ever done has been a

failure.”

His closest female

friend, Sophia Ryde, had ‘asked for more space in their relationship’ the week

before. A letter addressed to her, reportedly ‘expressing his heartbreak’, was later

found in his bedroom.

No-one will ever

know exactly what was going through his mind at the moment he put the first of the

30 Tryptyzol anti-depressants into his mouth, and lay down on his bed.

However Gabrielle, his older sister, said “I do believe that he

did want to die. I am not sure that [the pills] would have killed him if he

hadn’t wanted to die.”

His mother found

him in the morning with ‘his long legs’ stretched out on his bed.

He was 26 years

old.

“When the

game's been fought

Newspaper

blown across the court

Lost much

sooner than you would have thought

Now the

game's been fought”

Lyric from Nick Drake’s the “Day is Done”

-----

Nick Drake was

born on 19 June 1948 in Rangoon, Burma, where his father was working as an

engineer. When he was four years old his parents took him and his eldest sister

back to England in order for them to receive their education in Britain.

They moved to a

beautiful old house in Tanworth-in-Arden, which would be a bitter-sweet point

of reference for Drake for the rest of his life. “I don’t like it at home,” he once

told his mother, “but I can’t bear it anywhere else.”

While Drake did

well at school, excelling in music and sport, his headmaster wrote on his

report that ‘none of us seem to know him very well’.

And his father later added: “and I think that was it all the way through with Nick,

people didn’t know him very much.”

Drake’s mother

played piano, wrote songs and had her own rudimentary recording set up in her

home. His sister Gabrielle later said: “Nick may have been horrfied to hear this but

I am quite certain that he was very influenced by her whole chord structure and

way of composing.”

Apart from Drake’s sound, perhaps his

mother offers a further clue to both the fragility expressed in his lyrics and

his character in general, because in the documentary ‘A Skin Too Few’ Gabrielle suggests that she was a particularly

vulnerable person and that meeting and marrying their father gave her the

stability to both live and compose. While Drake cultivated a number of

friendships, he never seemed to find a deep intimate relationship that his

mother had found, and that seemed to ground her.

At school Drake played piano and various

other instruments before purchasing his first acoustic guitar at 17, on which

he rapidly learned to finger-pick. He began to write his own songs during the

six months he spent in Aix before heading to Cambridge University, to study

English in 1967. “We would get up, smoke

dope, skip lectures and play guitar… it was a three year holiday,” one

friend says about that time.

This period seems to have been the

happiest of Drake’s life. In one letter to his parents he writes “it may surprise you to hear that during the

last few weeks I have been extraordinarily happy with life and I haven’t a clue

why – it seems that Cambridge can do rather nice things to one if one lets it…

I think I have thrown off some rather useless and restrictive complexes that I

had picked up before coming here.”

Drake studied 17th and 18th century

writers and poets like Swift, Shelley,

Baudelaire and Blake, whose

literary and romantic influences can be seen reflected in his lyrics and, some

suggest, in the way he chose to live his life. “He used to look back on his Cambridge

days with quite a lot of nostalgia,” says his father.

It was during this period that Drake met

Joe Boyd, his producer, and signed to Island Records. “He was a songwriter of extraordinary ability and originality,” says

Boyd. Drake had clear the direction he wanted his first album to take and

enlisted his friend Robert Kirby to do arrangements. Drake was also accompanied

on the album by Richard Thompson from Fairport

Convention, and Danny Thompson

of Pentangle, among others. The sense of positivity and hope for the future can be sensed in

Drake’s lyrics for one of his classic early songs, River man: 'Gonna see the river man, Gonna

tell him all I can, About the plan for lilac-time.'

In 2003 Rolling Stone ranked Five Leaves left – named after a

reminder note that used to appear at the end of a packet of Rizla cigarette

papers - at 280 in its top 500 albums of

all time but, partly due to Drake’s reticence to perform it live, it did not

sell well. Producer Boyd felt that a tour of the college circuit was going to

be sufficient for the public to recognize his talent, but Drake quickly grew

disillusioned by people’s drinking and talking during his concerts, and at one

point walked off stage part-way through a song. “He was very shy and did not have much of a stage presence,” says

Boyd, “he could not charm an audience.”

Drake left Cambridge without finishing

his course and moved to London in 1969, where he continued to compose his rich

melodies.

Robin

Frederick, a songwriter who became friends with

Drake in Aix, describes his unique technique in the following way: “he combined Beatles-style chord progressions with the guitar innovations of

the British folk music scene of the 1960’s. But he immediately leaped far ahead

of his contemporaries in his use of cluster chords.” Drake also used

to detune his guitar – “an idea he

probably got from Bert Jansch (as did Jimmy Page), but his tunings were highly unusual, to say the least.

Even when playing a simple major or minor chord on guitar, he was often singing

the extension.” But why did he do it? Frederick’s response is because of ‘prosody’ – the link that Drake sought to

make between his tormented lyrics and beautiful melodies. “His dissonance and warmth,” she says, made him “some songwriter.”

In 1971 Drake released

Bryter Later on which he was

accompanied by John Cale from the Velvet Underground, Mike Kowalaski from the Beach Boys, and Dave Pegg and Richard Thompson from Fairport Convention, among

others. In 2000, Q magazine

placed Bryter Layter at number 23

in its list of the "100 Greatest British Albums Ever", but it sold

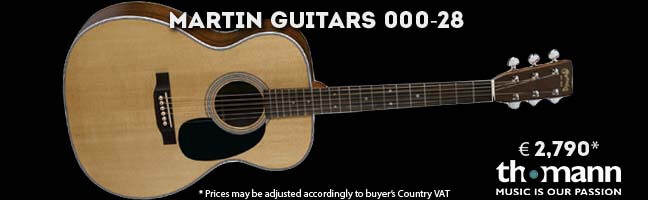

less than 5,000 copies at the time of its release. On the cover a Guild M20 can

be seen, but, like everything in Drake’s life, there is mystery about his

guitars as well. The Guild wasn’t his, and it seems that he didn’t use it on

the recording of Bryter Layter. There is conjecture over the guitar models that

he used throughout his career but the most likely is that they were a Martin

D28, a 00028, a Guild M20 (different to the one used on the cover) and a Yamaha

classic.

Bryter

Later was followed by Pink Moon in 1972, on which he decided to record alone in his

search for a more organic sound. Drake began seeing a psychiatrist around this

time, smoking large amounts of dope and appearing in an increasingly

dishevelled state, to the point that publicity photos that were taken for the

album cover were not used.

Pink

Moon again had poor sales, and Drake returned to

his parent’s home and became increasingly withdrawn. A friend at that time

recalls knocking on his door and when there was no answer, going around to the

back of the house, only to find Drake staring at a wall.

‘Black

Eyed Dog’, which formed part of Drake’s final

recording sessions in 1974, is perhaps

his starkest and most haunting attempt to directly express his depression. At

that moment he was no longer capable of playing guitar and singing at the same

time.

“Black

eyed dog he called at my door,

The

black eyed dog he called for more,

…

I’m growing old and I don’t wanna know,

I’m

growing old and I wanna go home,” he sings.

“I

don’t think he wanted to be a star, but I think he felt that he had something

to say… a feeling that he could make [people] happier,” his sister

Gabrielle says. “’If I thought that my

music had helped one single person it would have been worth it’ – he said

to our mother.”