The American Clapton

By Sergio Ariza

It’s 1965, Mike Bloomfield goes to Woodstock after getting a call from a folk singer he had met two years earlier in Chicago. Interested mainly in the blues and black music, he isn’t aware of the singer’s fame. At the bus stop with his ‘64 Telecaster, without a case, the young folk singer goes to pick him up and they return to his place to go over new material that he wants to record for his next record. The first one he shows him is Like A Rolling Stone. Bloomfield starts to play some blues riffs, but the author’s response was simply, “I don’t want you to play like BB King, no blues, play somethin else”. In the end, Bob Dylan, the young singer’s name, hears something he likes and gives him his approval. Four days later they were in the recording studio, after a fruitless session, the musicians are still trying to figure out the arrangement, and there’s a new guy there, a young guitarist called Al Kooper. Before starting, Bloomfield is toying with 2 or 3 solos and Kooper gets so intimidated by the talent of this guy, he puts down his guitar and goes into the mixing booth. After he hears the song, it occurs to him that a Hammond organ might fit in here, and starts to play on the half-hidden organ. When Dylan hears the result, he knows he’s found his own revolution. The young folk singer became the man of the decade and over time the most revered pop music figure of the 20th century, as for Bloomfield, he became the first American ‘guitar hero’, at Clapton's calibre, however he would be almost forgotten after struggling with chronic drug problems and his premature death in 1981.

Michael Bernard Bloomfield, born in Chicago in 1943, the son a wealthy Jewish family, but quickly learned that he was born on the wrong side of town. The young lad had no intention of following the family business and spent most of his time on the South side, lining up at all the juke joints to hear his idols. Chicago was the closest thing to electric blues paradise, Sonny Boy Williamson, Little Walter, Otis Spann and this style’s two greatest, Muddy Waters, and Howlin’ Wolf. It wasn’t long after hearing them that he was up on stage with them, at 17 he could already say he had jammed with giants. He was one of the few whites to whom they bestowed the privilege.

However, in the early 60s, blues was being forgotten and what pushed it aside was revival folk , so Bloomfield switched to acoustic guitar without forgetting his blues roots, playing with veterans like Sleepy John Estes and Big Joe Williams, and he even opened an acoustic folk/blues joint called the Fickle Pickle. This is where he would first meet Bob Dylan, where he first got enthused by his playing. A year later he moved to New York, in search of a recording contract.

At the beginning of ‘65, once again plugged into his Telecaster, he became one of the best guitarists around and Paul Rothchild, president of Elektra, invited him to join the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. At first there were reservations , Butterfield was a man with a big ego, and he didn’t want to share the spotlight and Bloomfield knew of his reputation as a hard band leader. In the end they smoothed things out and formed one the first blues rock bands in history, the first thing they recorded was Born in Chicago. They were one of the first racially integrated bands in the country with a rhythm section formed by Sam Lay and Jerome Arnold, ex-components of the Howlin’ Wolf band, Elvin Bishop on guitar, Mark Naftalin on keyboards and Butterfield himself on harp and lead vocals.

In June Bloomfield gets a call from Dylan, together they not only recorded Like a Rolling Stone, but one of the most significant records in history, Highway 61, where his frenetic way of playing can be enjoyed on Tombstone Blues. Dylan wanted him in the band at all costs and he signed him up for his first electric concert in Newport. The volume of Bloomfield’s guitar made many of the most die-hard reactionary folk purists lose their minds, but that’s not why he chose to give up on Dylan and go with Butterfield. He was a bluesman and as much as he liked Dylan’s new music, he knew that he wasn’t going to have as many opportunities to shine as he would with Butterfield. He wasn’t wrong, in September they recorded their first album and overnight he became the most important guitarist in the country. And with good reason, the album arrived a year before Beano by Mayall with Clapton and three years before Fleetwood Mac’s first. However, if anyone wants to hear what calibre he had at that moment, go listen to his version of Blues with a Feeling.

In July of 1966 East-West is released and a generation of musicians were awestruck. Many considered it their crowning work, broadening the band’s palette with incursions into rock and soul, never forgetting the blues as in the masterful I Got a Mind to Give up Living. Yet, the two most influential numbers were instrumentals, Work Song, and the title cut. The latter, written by himself, is the one to open the road to the extensive jam sessions of the late 60s and made way for acid rock. Building pillars to the San Francisco rock sound that was made popular by Jefferson Airplane and Grateful Dead. 13 minutes where Bloomfield performs a tribute to Coltrane and Indian raga. The USA already had their ‘guitar hero’ and from England Clapton called him “music on two legs”. But East-West put an end to his relationship with the band. Helped by the presence of Bloomfield, Bishop had become quite a good guitarist and also wanted his space, so he decided to quit and find new sounds.

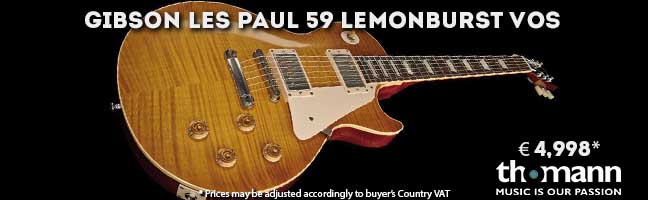

That’s how in February 1967 Electric Flag was formed, alongside his friend Nick Gravenites and Buddy Miles. Also there was Harvey Brooks and Barry Goldberg and a wind section. Bloomfield had visions of a great band that played American music, blues, soul, B.B. King and Otis Redding, Buddy Guy, and Steve Cooper. Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman signed them up on the spot and Peter Fonda asked them to record the soundtrack to The Trip. In case the good omens were few, the band played their debut show in June at the Monterey Music Festival, the very place the white American public discovered Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Otis Redding. It was a successful performance, and led to the debut of the most iconic guitar of his career, a Gibson Les Paul Standard Sunburst from 1959. His interpretation of Wine is one of the biggest moments of the festival and the expectations of the group went through the roof. However, instead of riding the wave and recording a record, the band fell into a spiral of drugs and recording sessions, changes to the band members, so when they finally made it to market, it would be a commercial flop. Still, A Long Time Comin’ is a great record with stellar moments such as Wine, Killing Floor, or the fabulous blues Texas, composed by both Bloomfield and Miles.

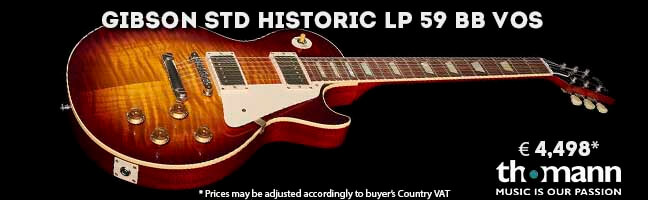

But the fight over leadership was won by Miles and Bloomfield left the band. Their divorce, his chronic insomnia, and drug problems didn’t help much. He was brought out of this stupor by Al Kooper, the man he had inadvertently turned into one of the best organists of his time. He had just left his band Blood Sweat & Tears and was now working for Columbia. He still considered Bloomfield as the best guitarist he’d ever seen and decided to create a session `jazz style’ but focussed on rock, leaving room to improvise. In May 1968, he rented a studio and the magic began to flow. Bloomfield played like never before with his Les Paul plugged into a Twin Reverb, with no other effect but the magic his his fingers and his incredible tone. In less than 6 hours they recorded 5 juicy songs and went to bed. Supposedly they had to finish thee recording the next day. And when Kooper woke up he found a note from Bloomfield saying he’s left because he couldn’t sleep. He never knew if this was true but without much time to weep, he got out his agenda and called Stephen Stills, a recent ex- Buffalo Springfield, to help him finish the album. When they had finished, he decided to call it Super Session, paving the way for many other ‘super groups’ that were getting together. It was on the market by July and was an instant hit, the best of Bloomfield’s career, but he didn’t see it that way, and thought the title was a ripoff , and reacted against stardom. Still, when Kopper called him to play live, he accepted.

September 26-28 at the Fillmore West they showed once again the chemistry they had, with amazing results as in Don’t Throw Your Love on Me So Strong, but on the last day Bloomfield vanished again. Kopper had to whip out his little black book to call a few friends, from Steve Miller, Elvin Bishop, or an unknown Mexican from the San Francisco scene, called Carlos Santana. The young prodigy couldn’t believe it, he was going to play with one of his idols, but Bloomfield didn’t show. Santana recalls it as one of the biggest opportunities of his life, but says he would have changed it for an opportunity to play with Michael.

In December they got back together again in a concert that served to bring Johnny Winter to a large audience. Bloomfield, however wasn’t at his best. The drug troubles and insomnia were taking their toll. Even so, 1969 proved to be an important year for him, wonderful collaborations on records by Janis Joplin, Muddy Waters and Mother Earth, besides his solo debut, It’s Not Killing Me, and a spectacular live show with Gravenites that would yield two records, Live at Bill Graham’s Fillmore West and My Labors, where you’ll find a gem called Moon Tune. His playing shape was at the top, but his demons were too. A year earlier he had declared, “Without my guitar I am a poet without hands”. At 26 he lost his hands. His heroin addiction got worse and made him lose interest in playing. The 70s were a slow descent into hell. If he had died in 1970 like Hendrix and Joplin, he would be as missed as them. But no, he would live 11 more years, after a decade of decadence away from the spotlight .

In November 1980 he took the stage with Dylan to play Like a Rolling Stone, and Bob took 10 minutes of the show to introduce him and sing his praises, Bloomfield sounded in top shape. To this day he still considers him to be the best guitarist he ever played with. He never had the impact of others but is the closest thing to an American Clapton . He didn’t have the luck, despite the promising reunion with Dylan, he wasn’t able to shake his demons ...and death found him on February 15, 1981.

An overdose took away the wizard of the 6-string, but the world didn’t seem to mind. He still hasn’t received the recognition he deserves. He wouldn’t have cared much though, being a rock star wasn’t his way, but that doesn’t mean that those of us who consider him one of the greatest don’t feel it’s a shame that the man who played elbow to elbow with Muddy Waters and Buddy Guy in Chicago at 17 years of age, who, at 22 played on a song that would change history, a year later he was the pioneer of rock jams, and who, at 25, formed part of the first rock supergroup, doesn’t get the impact he deserves.