Muddy Waters, the original Rollin’ Stone

By Sergio Ariza

The blues had a son and his name was rock and roll, of course the kid was a bastard, and had more than one father. Among them, one of the most important was McKinley Morganfield, better known as Muddy Waters, born April 4, 1913 (or 1915), who was the link between the delta blues and rock, or, if you like, between Robert Johnson and Chuck Berry. The blues and rock will always be indebted to the original Rollin’ Stone.

Born in the Mississippi Delta, Muddy Waters never had his first guitar until he was 17, it was a Stella that cost 2 bucks 50 cents, and with her, he began earning a living doing covers of his local idols such as Son House, his biggest influence, or the legendary Robert Johnson. But it wasn’t until later on when his first opportunity came up. In August of 1941, Alan Lomax headed to the Delta to record rural black blues artists for the Library of Congress , people like Son House and Robert Johnson. Johnson had been dead years before but if he could get to record House and a young Muddy Waters from which he left proof on various recordings. A bit later he sent Waters a couple of copies and a 20$ bill as payment. Muddy couldn’t have been happier, it sounded professional, all that time listening to his idols had paid off. The first track recorded spoke tons about his sound, Country Blues. But despite the immense quality of the recording, it wasn’t his great contribution to the genre, he now played like a professional bluesman yet just another of a long line of Delta bluesmen. So, in 1944, he moved to Chicago where he found his real sound and would define the sound of electric blues forever.

At the beginning of his career he worked the day and performed at night. His big break came from one Big Bill Broonzy, the main bluesman in the city, who let him open for his gigs. It was at this time when he bought his first electric guitar and he looked for his first band. By 1946 he hooked up with 2 future legends like Little Walter on harmonica and Jimmy Rogers on rhythm guitar. At the end of that year they began recording for Aristocrat, a label founded by brothers Phil and Leonard Chess which would shortly change the name to Chess Records and become the absolute Mecca of electric blues.

The first recordings to make him a name were Gypsy Woman and Little Anna Mae, recorded in 1947 with the sole accompaniment of Sunnyland Slim on piano. The next year came his first hits with I Can’t Be Satisfied and I Feel Like Going Home, his deft touch with the slide guitar made it clear that Chicago Blues had found their Messiah. In 1950, Aristocrat became Chess Records and as their second entry in their catalogue was Rollin’ Stone, a song that 12 years later would inspire the name of “ the greatest rock band of all times”.

His place as the most important figure of the genre was evident not only in the studio, but on stages at venues where Muddy and his band performed and became legend. Besides the aforementioned Walter and Rogers, Baby Face Leroy played drums, and the great Otis Spann was on piano. Known as the Headhunters they played in all the Chicago juke joints where other bands played first, and when they were done, the boys would take the stage. By the end of the night, the Headhunters had owned yet another stage (and another job).

In spite of it all, Chess didn’t let them record live until ‘52 or’53, Mad Love being the first appearance of Otis Spann on a Muddy Waters record. By this time Little Walter was already a star on his own account having become the most important electric harp man in the history of the blues. For sure, Chess kept calling him and paying him each time they had a recording session with Muddy Waters.

It was also at this time in Chicago when the only person capable to rival Waters for the title of King of Chicago blues appeared: Howlin’ Wolf. Upon his arrival in town Wolf holed up at Waters’ place where a rivalry soon started,which though friendly , would reminisce the rivalry their Delta mentors, Son House and Charley Patton, had had before them . The result depends on taste, but what remains clear is that it made them better, and their competitiveness made those years the golden age of electric blues. If Wolf was the professional leader who demanded his band to dress correctly, and not to smoke or drink on stage, the Waters group would take the stage drunk, with the frontman leading the charge. Not in vain were they called the Muddy Waters Drunken Ass Band. The rivalry was also a point of friction in one Wille Dixon. The young bass player became the leading composer for Chess and provided songs to both Waters and Wolf, the first to Waters with I Just Want to Make Love to You or Hoochie Coochie Man, while for Wolf he wrote Little Red Rooster and I Ain’t Superstitious. Despite the excellent caliber of the material, Wolf always suspected that Dixon was giving his best stuff to Waters. So much so that Hoochie Coochie Man became one of his signature songs that another young bluesman recently acquired by Chess gave new sound to. We’re talking about Bo Diddley who would gain fame with I’m a Man. Rock and Roll was on the way but Muddy Waters wasn’t going to be left behind and he would take Diddley’s tribute/theft and return it with Mannish Boy, another of his best hits.

Whereas his sound was one of the pillars that supported rock and roll, maybe his biggest contribution to the genre came in May of ‘55, when he suggested to a new arrival Chuck Berry to go visit Leonard Chess on his behalf. “The blues had a son and rock and roll was his name” he would sing in one of his later songs, if they switched blues by Muddy Waters and rock and roll by Chuck Berry, that works too.

But back to our hero’s career, while the world was exploding with the new music, Muddy Waters kept churning out classic after classic, in 1956 he put out gems like Trouble No More, Forty Days & Forty Nights or Don’t Go No Farther. In December of that year he would record another of his iconic numbers, Got My Mojo Working where his new harp man James Cotton substitutes Walter.

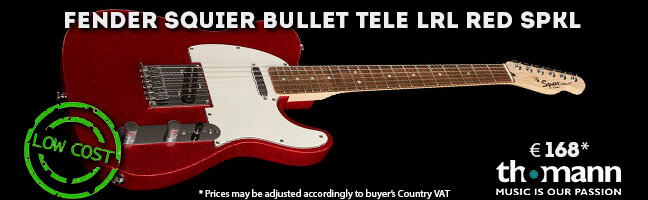

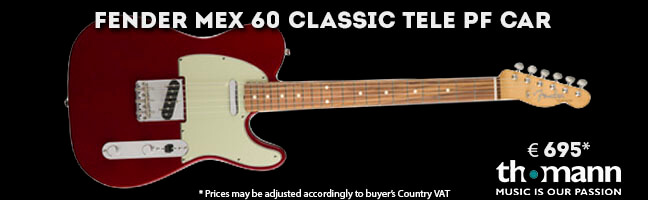

The coming of rock and roll moved him away from the charts but his material at the end of the 50s was still as good as ever with songs like Walking Thru the Park with a solo close to the new genre. The new decade couldn’t have started better with the release of the mythic live album At Newport 1960 that captures his performance accompanied by a stellar band: faithful Otis Spann on piano, James Cotton- harp, Andrew Stevens - bass, Francis Clay on drums and another guitar wizard Pat Hare. On this album, as on most in his career, Muddy plays a Fender Telecaster, but this time it’s about a golden 50s model instead of his legendary red Telecaster that he played from the end of the 50s until his death in 1983. To confuse things further, on the album cover he appears holding a semi-acoustic guitar that belonged to his mate John Lee Hooker.

However, after his overwhelming start, the 60s saw the blues giant waver for the first time, despite songs like You Shook Me or I Need Love, which Led Zeppelin took note of, or records like Folk Singer, the singer/guitarist made some false moves focussing on some new fads of the moment as in Muddy Waters Twist, or near the end of the decade with Electric Mud, a record in which he mixes guitars with a Hendrix feel, and traces of psychedelia that didn’t fare well with his voice and music.

But as in all great stories, Muddy Waters hadn’t yet had his final word, and the 70s saw his renaissance. First was his splendid performance at The Last Waltz, the closing act of The Band where Waters appears together with the best roster of 60s rock, Dylan, Neil Young, Van Morrison or Eric Clapton, playing a lovely version of Mannish Boy, then later another essential record was released, Hard Again, in 1977, produced by Johnny Winter, who also played on it, and Cotton on harp. It was as if Waters had found his voice anew, in full form on numbers like The Blues Had a Baby and They Named It Rock and Roll, Pt.2, or an amazing rendition of Mannish Boy.

Throughout the following years Waters toured non-stop, lavished with public affection that saw him as the giant of Chicago blues. Finally on April 30, 1983 his heart stopped beating. For sure his music is as alive as ever. He was the one who took blues out of the country and plugged it into the city. Without his contribution rock and roll would be impossible and his enormous legacy can be traced in folks like Chuck Berry, the Rolling Stones, Eric Clapton, The Allman Brothers, Led Zeppelin, or Jimi Hendrix. His juju still works after death.