Peter Green and the Holy Grail

By Sergio Ariza

“He has the sweetest tone I ever heard; he was the only one who gave me the cold sweats.” Let’s heed the king of blues

guitar and consider Peter Allen Greenbaum, born the 29th of October,

1946, London, among the greatest guitarists of all time, someone clearly

recognisable in each beat and capable of thrilling more with three notes than

any pyrotechnic of the 6-string with 20, in the great tradition of the late B.B.

King. But, Of course, while King was at a very high level playing for over

70 years, the time Green was playing at his best is cut down to between

1967 and 1970, years in which Peter Green was Clapton after Clapton,

and Jimmy Page before Jimmy Page, or put simply, the successor of

the first and the predecessor of the second.

Everything surrounding Green is soaking in legend

and myth, his mental decline, due to drug abuse, impeded our enjoyment of one

of the essential British guitarists, someone who, if not for the circumstances,

could have been put in the category of a Clapton or a Page, two guitarists who

have always been considered among the greats. He, like them, knew how to

provide his own vision of blues rock, getting close to ‘hard rock’ at times,

yet at his r best he is bound to the sweetest sound ever heard. Part of

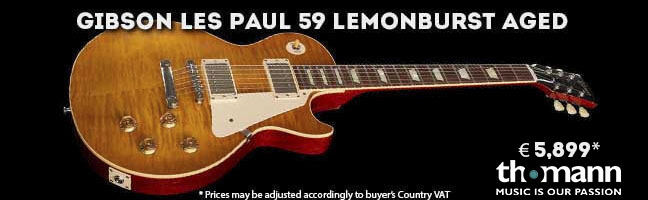

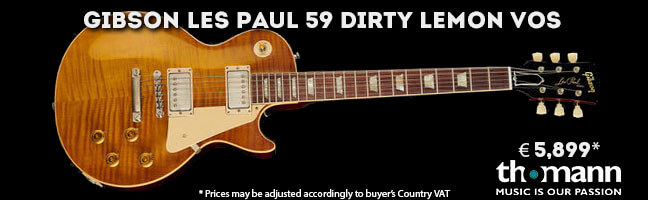

the blame of this sound goes to the guitar, known among the experts as

the Holy Grail, a Les Paul Standard from 1959, with ‘magic’ powers, able to

sound like a Les Paul, yet something completely different, what some like to

identify as a Stratocaster, but more itself and unique. Its story goes totally

tied to the mythic ‘Greeny’.

His career started as guitarist in a band called the Peter

B’s Looners, of Peter Barden, where he met e t drummer Mick

Fleetwood for the first time. He made his first recording with them,

but it was the following year that he got a slap on the back to his career when

he got the most cherished spot of all British guitarists: to substitute Clapton

in John Mayall's Bluesbreakers. It was in these very times that Peter

Green, just as Arthur did with Excalibur, found the ‘magic’ in his Les Paul.

Strangely enough, this was after seeing Clapton with another mythic guitar, his

Gibson Les Paul Sunburst to which they nicknamed ‘Beano’( the name of the comic

on the album cover of the only record made by Mayall and the Bluesbreakers).

Now that Clapton had left to form Cream, John

Mayall could pick someone among the best U.K. guitarists, to fill his boots.

His choice showed that he knew how to find a player. When he arrived at the

studio without Clapton, one of the producers at Decca took a look at the

guitar amp and saw that it wasn’t ‘Slow Hand’s’, so he inquired about the star.

“He’s not with us anymore, he left us weeks ago. But don’t worry, we got

somebody better.” Green didn’t want to put his boss on the spot, so, in return,

he wrote the best song on that album, called ‘Hard Road’, the

instrumental ‘The Supernatural’, which could be considered the

foundation to Fleetwood Mac, as well as the predecessor to his

most mythic numbers, ‘Albatross’. The personal, special sound that

Green got from his Les Paul was considered one of the top 50 of all time by

Guitar Player magazine. It’s this particular sound of ‘Greeny’ that is stuff of

legend. They say that one of the pick-ups was inversely set due to factory

error,which gave it a sound out-of-phase and sounded truly unique

and recognizable.

His time with the Bluesbreakers was brief and

profitable, leaving an impact of Clapton proportions. When he decided to make

his own band in 1967, Green was already a star and had his own nickname; if

Clapton was ‘God’, Green was the ‘Green God’. But at that moment,

his rebel side was revealed, fed up with praise and big egos that guitarists

had, Green decided to baptise his new project with the surnames of his

favourite drummer and bassist, who he had played with in the Bluesbreakers,

Mick Fleetwood, and John McVie. The first accepted without hesitation,

having had troubles with Mayall and his drinking, McVie joined some months

later. For the finishing touch of the band, Green recruited a young prodigy,

Jeremy Spencer, who played slide guitar, and could take the spotlight off

himself somewhat. To the point where the first single on the album, ‘I

Believe My Time Ain’t Long’, a version of ‘Dust My Broom’ by

Elmore James, was sung by Spencer.

Shortly after, ‘Fleetwood Mac’, the band’s

first record, was released in February 1968. It’s a collection of blues

classics, like ‘Hellhound on my Trail’, by Robert Johnson or Elmore

James’ ‘Shake your Moneymaker’, and some originals too, 5 by Green,

and 3 by Spencer. While Green’s songs like ‘Long Grey Mare’ or ‘Merry

Go Round’ are spectacular, those of Spencer weren’t at the same level. His

effort to skirt the limelight and share the load of the band yielded records

that never reached the category of what he once had. Yet, in spite of it all,

he became ‘the next big thing’, with the whole music world considering

Fleetwood Mac and its leader as having the brightest future in the British

record industry.

The following steps would prove them right, the group

released the amazing singles ‘Black Magic Woman’, a Green original that Santana

made a global success two years later, and ‘Need Your Love So Bad’, the

song that B.B. King must have been thinking about when he said that line at the

beginning of this article. These songs show that Green wasn’t just a great

guitarist but also had a voice right up there with the original bluesmen that

had influenced him in the first place. The demand was so great that 6 months

after his debut album, the shops were selling the band’s second record, ‘Mr.

Wonderful’. A record that took noticeably too little time to make, with 4

songs starting with the same riff lifted from Elmore James, courtesy of

Spencer. In October 1968, Green decided to bring another guitarist on board,

the young Danny Kirwan, 18, after seeing that Spencer was bringing very

little to the work. This move paid off and the first song recorded with

the ‘new’ band was the instrumental ‘Albatross’, which became their

first #1 hit on the British charts. Edited the 22nd of November 1968, the song

was a Green composition based on a famous hit from the 50s called ‘Sleep

Walk’ by Santo & Johnny. Spencer didn’t play on the song

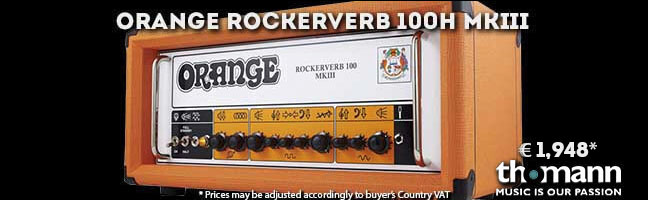

and Green never used ‘Greeny’, but instead a Fender Stratocaster hooked up to a

Orange Matamp OR100 amplifier. It became a hit sensation in his native England,

influencing players such as David Gilmour of Pink Floyd and even

the Beatles, whose ‘Sun King’ from ‘Abbey Road’ was based

on it.

Its sequel, in April of ‘69, would be the absolute

confirmation of the group, ‘Man of the World’ another classic penned by

Green in which he gets back to expressing his disgust for fame, although,

paradoxically, the record shot to the top of the charts at #2 in England. On

this record we hear the unmistakable sound of ‘Greeny’ on one of the most

remembered solos. Shortly after the band started to record their 3rd album, ‘Then

Play On’ released in September, the first with Kirwan as a full member.

During these very sessions he recorded another of his undeniable classics, ‘Oh

Well’, a song over 9 minutes long, composed by Green, split in two distinct

bits, the first built of a powerful riff close to ‘hard rock’, and the

second, an instrumental where Green plays a Spanish Ramirez guitar with classic

influences. The second part was the favourite of Green himself, who wrote it in

the first place, but it was the shape of that powerful riff, with the band

joining in, then a big pause when the voice comes in that inspired one of

Green’s biggest followers to write one of the most famous songs in history:

we’re talking about Jimmy Page and ‘Black Dog’. Page has always

recognised Green as one of his influences and when they got together with the Black

Crowes to record ‘Live at the Greek’ some classic Led Zeppelin

hits, and ended off with ‘Oh Well’ by Fleetwood Mac. ‘Then Play On’

also included a Green classic, ‘Rattlesnake Shake’ one of drummer Mick

Fleetwood’s favourites which he considered a good way to ‘jam’ like the

Grateful Dead.

With ‘Oh Well’ at #2 on the charts and ‘Then

Play On’ among the 10 bestselling records, everything was going as smooth

as silk for the band even having started to appear on the U.S. charts, a

country where he had performed with great success with Ten Years After.

But it was all about to go up in smoke. Peter Green’s health started to teeter,

and his abuse of LSD did nothing but make things worse. The key moment,

according to bassist John McVie was in Munich, March 1970, when Green ended up

in a hippy commune tripping on acid from which he never fully recovered. At

first he decided to stay in the commune and didn’t leave until the rest of the

band found out his whereabouts and took him out of there. But something had

changed, Green had become obsessive with his rejection of stardom and the

wealth that carried him. He tried to convince the band to give their money and

possessions away, but when they said no to that, he quit the band. But not

before giving a last shot with lucidity and talent on a last song recorded

before leaving for good: ‘The Green Manalishi’. A song which compared

money with the devil and seemed to faithfully document his struggle to detain

his descent into madness. To everyone’s misfortune, he lost that battle. His

last gig with Fleetwood Mac was May 20, 1970, five days after ‘The Green

Manalishi’ hit the market.

His career and special way of playing would never be

the same. In June of 1970 he accompanied his ex-boss John Mayall in a show and

around the same time he recorded a jam session that would be edited in December

under the meaningful title ‘End of the Game’, a record that got away from his

sound in Fleetwood Mac, but rather something more Hendrix with distortion but,

undoubtedly, without his talent and magic. It was evident proof that something

had broken him inside, which he would never get back. As with the magic, the

same with the guitar, just before leaving Fleetwood Mac, a group that he

himself had created, Green started giving away his possessions, the most

precious landed in the hands of a young Irish guitarist hardly 18 years old.

We’re talking about Gary Moore. He told Green he couldn’t deal with the price

of the guitar, but he answered saying he would give ‘Greeny’ for what he could

get for his guitar a SG. Moore accepted the deal and paid Green 300$ for it. In

2006, when he was pressed with money troubles, he decided to sell it. He got 2

million dollars for it. Eight years later it would end up in the hands of another

guitar wizard, Kirk Hammett on the advice of Jimmy Page, he managed to get

the Holy Grail of guitars and ‘Greeny’ returned once again on a record,

specifically: the last Metallica album.

As for Green, he would return from the hell of

dementia and schizophrenia (the hell that got him admitted to various psych

clinics and got ‘electroshock’ therapies they used in the 70s), but would never

sound the same. He even returned to play on a Fleetwood Mac record,

specifically on ‘Tusk’, with the definitive band, Lindsey Buckingham,

Stevie Nicks, and Christine McVie, however his performance wasn’t

registered. At the end of the 90s he managed to tour with his group Peter

Green Splinter, and got a warm reception from the public. There were even

attempts by Gibson to make a Les Paul Peter Green, but after parting with

‘Greeny’ he went on to a Gibson Howard Roberts Fusion and nothing came of it.

The mold had broken long ago, and nobody, not even he himself was able to

repeat “the sweetest sound” ever heard on an electric guitar.