From the queen of blues to the godmother of rock, two female legends of the guitar

By Vicente Mateu

With traces of cotton fibres still

on their fingers, their hands strummed the guitar with a woman's sensuality and

the rage of their ebony skin. Their voices still engage us almost a century

later, with their vintage recorded sound blending blues, gospel and jazz right

up to the first tentative steps towards rock 'n' roll. Their names are Memphis Minnie and Sister Rosetta Tharpe, two kindred six-string spirits in America of

the 1930s and 1940s who even died at virtually the same time, the former in

August 1973 and the latter two months later. Two legends who were born to find one

another.

Legends of the guitar, of course. Elizabeth ‘Kid’ Douglas (Louisiana,

1897) and Rosetta Nubin (Arkansas,

1915) are the symbols and models for every woman who picks up a guitar; two

fighters who triumphed in a closed society through their talent and, above all,

their deep sense of blues. Their guitar technique, comparable to their male

peers, guaranteed them a renown that was only driven home by two of the finest

female voices to ever sing the blues. Memphis

Minnie and Sister Rosetta were

making their mark in a world dominated by men.

They both developed their careers

at practically the same time, between the '20s and '50s. Both travelled very

different routes through the Deep South in the first half of the 20th century,

building up experience until they found their destiny in the same windy city,

the legendary Chicago.

The Queen Who Died in Poverty

Minnie holds the place of honour in

the encyclopaedias of female guitarists, even beyond the blues. A position that

simply can't be argued with -along with boasting one of the great voices of the

genre- thanks to a legacy of close to 200 recordings, the first made in 1929

and the last one two decades later. Long enough for her to engage in her

trademark picking on the strings of the banjo she played when she was still Kid Douglas, as well as on the electric

guitar that amazed the clients of the nightclub in Chicago she withdrew to in

the '40s with her third husband Ernest

Lawlars, better known as Little Son

Joe. Everything stayed in the family.

However, authorities in the field

recommend the early recordings by Minnie,

100% unplugged and better than anyone could possibly expect playing a very

cheap guitar. The '30s were a very fruitful, productive decade for her, first

with her second husband Kansas Joe McCoy

and then with producer Lester Melrose

leading a group of musicians with full permission to experiment and explore

every whim of her voice and hands. The first of those legendary recordings for

the Vocalion label -Bumble Bee / I’m Talking About You- was an impressive

debut in every way and became a massive hit.

To be fair, her biggest hit was

performed on electric guitar, the first one she ever had and the first song she

recorded with it: Me and my Chauffeur

Blues, essential on any of the jukeboxes that were turning into another

symbol of the made-in-USA lifestyle of the time.

Many guitarists then and now

learned and continue learning from the woman known as the "Queen of the

Blues", although her legend didn't free her from dying in poverty, barely

able to survive thanks to the donations of friends and fans who were transfixed

listening to her in nightclubs. Bonnie

Raitt would pay tribute to her in 1996 by paying for a headstone for her

grave in Walls, Mississippi.

In December 2015, they are still

keeping her songs in circulation by releasing the first volume of her post-war recordings.

The Double Life of Rosetta Tharpe

Sister Rosetta Tharpe has been

called the "godmother of rock 'n' roll" for being the great female

influence on Little Richard and Chuck Berry. The one female guitarist

capable of outshining the great Minnie led a double life. By day, she was a

devout gospel artist but by night she was shaking to the very beginnings of

rock and rhythm & blues.

Two very different styles for the

same woman, who accompanied her mother with her voice and guitar on an

evangelical mission in the southern United States. And in 1944, with

electricity now coursing through her fingers, she recorded the first song

officially recognized as rock 'n' roll, Strange

Things Happening Every Day.

It was a complete success for

Decca, whose decision to back Sister Rosetta with Sammy Price's boogie woogie piano was right on the money. Twenty

years younger than Memphis Minnie,

she was heir to her style of playing and singing, too, because our sister Rosetta also had an exceptional voice.

Probably even better in fact. Her command of the guitar, even more so for being

a woman, catapulted her to fame from the trenches of the U.S. soldiers deployed

in Europe.

The age difference meant Rosetta enjoyed technology far superior

to her predecessor, who was retired by the time of Tharpe's emergence. What

interests us most about our 'sister' is the quality of her recordings because,

when talking about her guitars...to listen to them in their pure state, without

effects or amplifiers, is a sensation that goes beyond the simple pleasure of

listening to good music. There is something magical hidden inside her teasing

gospel rhythm which wound the clock of Bill

Haley and the Comets up a decade before they found out they wanted to rock

around it.

And suddenly you realize you're

listening to some of the first 'modern' guitar solos. Not just of blues

-although they are also good examples of that- but 'picking' that is almost too

reminiscent of the techniques used by Eric

Clapton or Jimmy Page to astound

their audience.

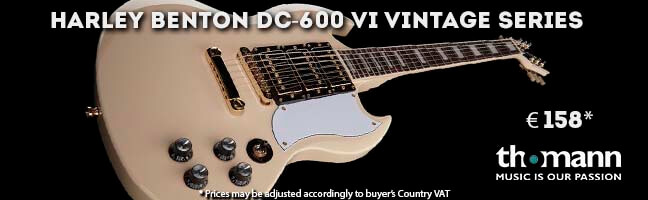

It's not at all surprising that

the rock and soul world would be attracted to someone like Sister Rosetta, who concealed the soul of a

transgressor with both her voice and her Gibson

SG behind a holier-than-thou image. But she was only able to show that side

of herself in the clubs and it led to problems in her other life, the one

dominated by religion, where neither a woman earning her living as a guitarist

nor, naturally, her style of playing gospel was looked upon favourably. Too exuberant, too swinging for a world still

resistant to change.

However, in real life her fame

would be eclipsed by giants like Mahalia

Jackson. She toured Europe with the big names in the '60s, when gospel and

spirituals came back into fashion and even sold some records. The 'girl

guitarist' was still something new then and she took as much advantage of it as

she could and climbed on board for what would be her final voyage.

On one of those European tours in

1970 with Muddy Waters as the

headliner, diabetes claimed one of her legs and she was forced to return to the

US gravely ill. Even though she managed to recover and even performed and

recorded again, her body gave out three years later. Memphis Minnie had died two months before, alone in a nursing home.

Mrs. Tharpe -the surname of the first of her three husbands- never

stayed still almost from the day she was born in Cotton Plant. She was a

complete artist, always searching for new ways of surprising her audience from

the time of her first performance at four years old! In the late '40s, she

joined forces with a young friend -and lover- named Marie Knight, gifted with a voice capable of filling any theatre or

club by itself.

Between the two, plus Sister

Rosetta's guitar, they armed a bomb that exploded in Up Above My Head, one of those songs that always gives you goose

bumps. Those were the golden years, when 25,000 people would pack a stadium in

Washington, D.C. to hear her sing and play after celebrating her third wedding

there in 1951. Sister Rosetta was

already a legend by then.

From the queen of the blues to the

godmother of rock. Two guitars shaped like the body of a woman, a recurring

metaphor that those two women, however briefly, turned into reality. Two female pioneers whose influence on 20th

century music is much greater than most biographers of the blues are willing to

acknowledge. Men, naturally.