Paul McCartney

Macca appears before his blessed faithful at the Vicente Calderón

by Alberto D. Prieto

You have

to put yourself in the shoes of the old guy. Up there in front of 50,000 or

70,000 people. Day in, day out. At 74 years old. For decades now. And with all

those intolerant fundamentalists of Beatlemania with their ablutions completed

who knows how many times a day since ...when?

Twenty, 30, 40 years ago? Fifty

maybe? There were those there, of course, the wrong side of fifty who had grown

up with him. And then there were those who still hadn't learnt their first

nursery rhyme at playschool and were already cooing Ob-la-di Ob-la-da in their mothers' arms.

You have

to put yourself in his shoes, I say, to understand that, yes, the Beatles existed and, yes, he was one of

them. At least 40,000 of the 50,000 people who filled Vicente Calderón to

capacity on Thursday, June 2nd 2016 were not around at the same time

as the quartet from Liverpool. When something is mythologized to such a degree,

when it's always been there in your life, when they are the centre of

everything popular music measures itself by – there were geniuses who sowed the

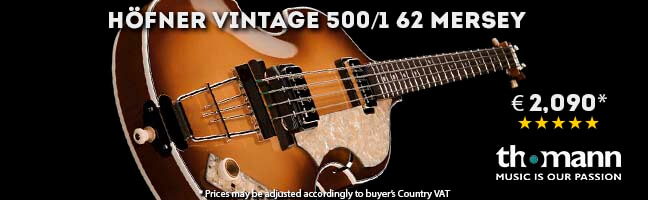

seeds for the rock 'n' roll of Rickenbackers,

Hofners, Gretschs, and Ludwigs,

and then came John, Paul, George and Ringo to turn

those seeds into bloom–, and when that happens, it's hard to believe that the

old McCartney up there on stage is

truly the same one that they project on the screens framing him.

Not

because of the wrinkles, because you already know the effects of the passage of

time on the body, no, not that. It's hard to believe because the gods are not

of this world. And if so many and such a varied assortment of gods have come

after him –all of them harvested from the original Beatles seed–, how can it be

that he's still up there, still here, still among us?

James Paul McCartney must have become aware

of himself at some time between Hamburg and his supposed death in a traffic

accident on November 9th, 1966. Maybe that's the reason why the

repertoire of this One on One Tour

reviews the entire musical life of the oldest god of the pop-rock Olympus. From

In Spite of All the Danger, when they

were a secondary school combo introduced as the Quarrymen, right up to his recent collaboration with Rihanna and Kanye West on FourFive

Seconds. From being nothing more than a teenager with a friendly face

playing at being the bad boy with John,

his pills and hookers in the German port city to being a legend so infinite that

everyone wants to confirm the alternative option.

Human

beings became conscious of themselves at some point between the moment they

climbed down from the tree and the time they first buried their dead with a funeral

ceremony. Back then, they looked up: outside the cave in search of God and

inside, searching for some place where they could express their creativity. And

there we were, all the little humans, in the Vicente Calderón, looking up at a

god incarnate who was sharing his choice morsels of wisdom with us. And he was

looking up, too, at his own particular heaven, where his old friends are

waiting for him, reciting one more time –so many times now–, his blessings, the

ones he composed with his long absent friends and honoured ceremoniously this

night on the ukulele for George's Something and at

the piano with the loving Here Today

and joyful Give Peace a Chance by John.

Left

behind were Stuart Sutcliffe, happy

in turning away from fame in exchange for the glory that Astrid Kirchherr, so brilliant behind the viewfinder, gave him; and

Pete Best, who missed the train, or

they lost him; left behind were the Beatles,

Wings, Mersey Beat, soft soul,

the grandiose forays into funk and classical, the joint efforts with other

gods (Stevie Wonder, Elvis Costello, Michael Jackson…), all that left behind. Today a pedestal is

erected every other night all around the planet for old Paul to stand on with his sad, prominent eyes, catlike pout and

that familiar voice we've known forever, that trembling voice on the verge of

tears.

But the

pilgrimage remains the same, because there are songs you have to hear live.

Because if music is made for anything, it is to be heard live, while it is

being performed and with the person responsible for writing the song among the

performers whenever possible. The

left-handed Macca strummed his first guitars upside down in cold post-war

Liverpool, in a world that was being reborn and registering new patents every

two days. Some were electric guitars, sound amplifiers, vinyl records, cassette

tapes... That very thing that entertained him would develop into a business at

the same time as his artistic spiral expanded its scope. Stimulated, of course,

by the same creative growth of his teenage partner, that madman Lennon. The

competition turned them into friendly enemies and their songs became rich in

meaning due to the synergy between the collective and the personal.

George Martin, the first of the 'fifth Beatles’, helped

them shape all that. To produce, record and package those essences that were

elusive and fleeting before. But nothing is comparable to being warned of the

clang of the string plucked by the pick milliseconds before the amplifier emits

the processed sound. Only in the sound of a live concert are those shades captured,

only in front of the musician do those milliseconds become apparent. The energy

that flows from the arena to the stage and back again is a real sacrament.

There are

songs you have to hear live and even more if they are those that opened up,

every one of them, a whole genre of popular music. If you can assume that

something is written by McCartney,

whether credited with Lennon or

solo, it's because the melodies just

pour out of him endlessly. The melodies

and the riffs. The melodies, the riffs and the arrangements…

It's a natural consequence among geniuses that everything they do, they do

well. And if they do a lot, they end up doing completely different things

really well too. Up on the stage in Madrid this early June was the guy who

wrote the lovely Here, There and

Everywhere and also the despicable Live

and Let Die, who was capable of inventing the soul-blues of Letting Go

coming out of skiffle and the simple

Love Me Do.

The

powerful band accompanying Paul

McCartney is made up of experienced musicians he has been collaborating

with for 15 years. To his left stands Brian Ray, a bleached blond from

California who covers the bass for 60% of the show, essentially with a Gibson

SG. But when Paul grabs the Hofner, Ray breaks out his six-string arsenal (plus one 12-string),

including a Les Paul GoldTop, several Taylor acoustics and two

huge bone-white axes, a Danelectro

and a '59 Gretsch. Rusty Anderson is

on his right, another 55-year-old from the U.S. who played with the Police

among many others, and whose friendship with Stewart Copeland brought him into

contact with McCartney 20 years ago. Since then he has become a fixture with

the ex-Beatle: Anderson, his Mesa Boogie

and Vox, primarily plugged into a Memphis ES 335 that Gibson custom made for him. Anderson's

solos during the show were unforgettable. The percussion is handled by Abe

Laboriel, a drummer with powerful arms and an unexpectedly good feel for a bluesy sound. It's not surprising he

has toured with Steve Winwood, Eric Clapton, B.B. King… and alongside him Paul

Wickens, Wix, Macca's faithful

companion since Flowers in the Dirt

in 1989 on keyboards, bass, tambourine... whatever is needed. His instrumental

base has been essential to the McCartney

sound for a longer period of time than any other musician on Earth.

Art offers

an opportunity to change the world and Paul

McCartney was given the chance to do that once and stay alive to see the

consequences. It's not that he spent five or six decades doing the same thing. We

simply remember what the soundtrack was to the world we know, and he wrote it,

that talkative old guy looking at us from up high on the stage, who observes

his creation every other night and sees that it was good, all of it, from Hamburg

to Rihanna, it was good. And although there’ll be time for him to rest, for now

heaven can wait. The day after tomorrow, there are more of the blessed faithful

to appear before.

(All images: © Cordon Press)