B.B. King

Because Lucille always wants more

By Alberto D. Prieto

"Lucille

took me from the plantation and gave me fame; when I'm lost, alone on the road,

she talks to me. Sometimes I can hear her cry. Nobody sings to me like

her….Sing to me, Lucille"

God writes straight with crooked lines. And

for Riley B. King, if there is a

god, He twisted things up for him since birth.

The Afro-Americans complain that the white man

has taken everything away from them, from their dignity to their liberty, and while

doing so robbing them of their son, gospel, blues, jazz, petit-band sound,

swing, r'n'b, rap and hip-hop…without so much as a thank you. All taken away

over just one century, the biggest heist in history, and with just one witness

of it all, one Riley Ben King

(Itta

Bena, Mississippi September 16th, 1925 – Las Vegas, Nevada, May 14th,

2015), spotless

in his suit and bowtie, well rounded and seated on his stool, nearing 90

years of age.

That was his name up until he was 24, when Blues Boy King made it big on the WDIA,

a radio station from Memphis, Mississippi. Oddly, he didn't do so as a singer,

but rather a disc jockey, presenting other people's songs to the city's

downtrodden black audience. Over the night waves, King would slip in some of

his own songs amongst the hits and promote his own concerts. Gradually, he

gathered together a following in the smoky drinking-dives of the post-war

south.

The

whites took nothing away from B.B. King, however; the nearest they have gone to doing so is by

copying him, taking inspiration from him and perhaps even worshipping him. After

all the years of success, oblivion, comeback and revival, all the whites,

blacks and yellows wanted is to play along with him, to bathe in the magic of his

fat cat voice, his leisurely playing of the guitar.

It was in a town with an apt, musical name, Twist, in which, after one of those

gigs that had been plugged on the radio, B.B.

King named his guitar. Lucille got her name in 1949 from a woman whose

supposed beauty was the cause of a fight in the dive that King was playing in. The scuffles that broke out in this lost

Arkansas wasteland soon turned nasty. Pushes came to shoves and then the

flashing of knives and in the blink of an eye a barrel of burning kerosene that

served to keep the locals warm on that cold winter night was overturned. The

wooden building was soon engulfed in flames. B.B. King managed to escape the inferno, but realised he had forgotten

his guitar. Rushing back in to recover it, he found out the cause of the

rumble. Afterwards, he christened his guitar Lucille, vowing never to do such a reckless thing again.

The following day, he found out that the

two men who had started the fight had both died. From then on, the bluesman

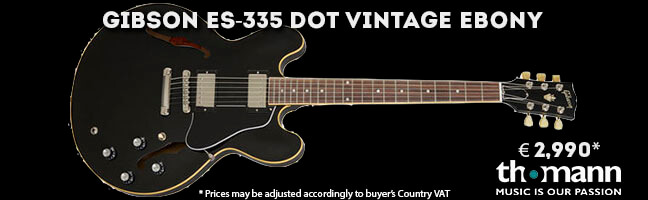

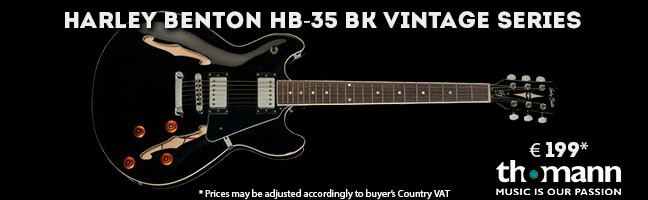

stayed faithful to the model: an

adaptation of the Gibson ES-335, usually black, with no vibrato arm or f-holes,

with a semi-hollow, maple body. King's sound is not so much thanks to his

guitar but more the way he talks to her. In fact, in all probability, his first Lucille was a solid-block Fender

Telecaster.

Recently arrived from Memphis, Riley met his cousin, a bear of a man called Bukka White,

who got by playing his silver steel acoustic. Bukka showed the youngster the

ropes: “If you want to be a good blues singer,

people are going to be down on you, so dress like you’re going to the bank to

borrow money. They have to trust you if you want to rob them.” Bukka White always had a slide on his

little finger, and B.B.'s

interest in nailing that glacier metallic sound could well be the origin of his

unmistakable vibrato picking style today.

They were the first

generation of black people born into freedom in the USA. To survive, be it a

tradition of the victors and the vanquished or for whatever reason it may be,

the only way a black man could get on in life was to know that he was inferior,

know it deep down in his bones, in everything that he did, in everything he

said. In a word, to be less than the white men that exploited him. Such knowing

implied a deep feeling of tragedy and a contradiction. Tragedy gave character

and was expressed in everything this new social class born from the Africans

imported in to serve the New World did. The contradiction lay in the submission

in order to survive and the instinctive desire to rebel. It was a contradiction

that worked to bring the black people together to share their culture and their

ways of life. It was a limitless energy that the bluesman channeled, transmitting feelings, traditions and power to

be shared by this black brotherhood. Their music, a connection to their

roots and a source of redemption, was part of their destiny.

It would be difficult

to decide which transcends the other in

B.B. King's blues - his plaintive voice or Lucille's. It would be difficult,

if it were not for the manual element of learning how to play the guitar. The

soft prodigious way he hits the strings, as much an innate talent as his voice

is, gives nuances and feelings that take his music up to another level.

Nevertheless, it is also true that if

King weren't a key figure as an American blues guitarist, he would be anyway as

a singer.

The old man's voice is even more recognizable

than his large and rounded figure, that big black and white silhouette that springs

to mind whenever we hear the first notes of his blues songs. Each note lasts an eternity, the clean ring

taking its time to fade away. With the passing of the years, each decade of

the black music scene has seen a change from blues to jazz, from jazz to funk, from funk to r'n'b, gaining in popularity as the

whites little by little started marketing it. With every show, B.B. King

demonstrated the versatility of his talent to ever-growing audiences, while

never losing contact with his bluesman roots.

God writes slowly on crooked lines and it

is important to keep in mind that B.B.

King is the grandson of freed slaves. This means that his parents'

generation, the generation that brought him up, kept all of their slave

customs. As did his grandparents, who

were grandchildren of Negros that still missed their native Africa and had

to survive under the white man's 'law'. This means that the blues king of this

21st century is a direct living link to the wooden shacks of the plantations,

bringing us the sound of that age to Spotify.

There exists a musical standard, one that

has reigned for a century called A440.

This standard dictates that the musical

note A above middle C sounds best at this frequency, and therefore all

notes in its scale sound better. There is another tendency, called A432, which insists that A at 432 hertz gives

a richer mood when playing melodies, giving a certain melancholic feel to

the music. A similar tendency exists in the origins of the blues, which called the

flattening of the note a half tone, making it sound sadder, bluesing it. Why? Probably because of

the non-academic origins of black African or black North American music, which

at the end of the day comes to be the same thing. Or at least it used to.

The blues

is born from a tortured soul, from misery, and above all from injustice. For

this reason the minor scale was so suitable for this style, when the fight for

the black vote started, when crowds of black people went to the clubs to live a

little, where anybody living in one of

those old shacks had lived enough to be able to get in down in verse and make a

ceremony of their difficult lives. That and the African tradition to not

teach music, but to express it as a very part of one's life made this style

(and all of the black styles to follow in its path) a music of truth.

Therefore, anyone seen to be a blues

virtuoso would be venerated as a living legend: a bodily unification of the

truth and the perfect way to express it.

Be the lines straight or crooked, it's

difficult to be a legend while still living, even more so for decades. And this

is only possible if you always tell the truth, something inevitable if you have

not had the time to do anything else with your life.

You

will probably never hear King and Lucille speak at the same time. Their blues dialogue, note by note, is respectful of one another,

each taking their turn. Lucille can be

heard even without an amp, as B.B. King takes his music from the depths of his

heart. That's what makes his sound so characteristic, "just a single

one of his notes is recognizable", assures Eric Clapton, one of his disciples. And so are his gestures, just

like they are of a flamenco dancer. When it is the soul that is making the

music, the notes are not really looked for, but rather they themselves queue

up, vying to be used. That's why King

isn't afraid of the moments of silence out on the stage. Sing and play, sing

and play. And when he sings, he makes pauses, to hear himself, to listen to

what is being played within… It's now not so difficult to understand how Beethoven

could compose while deaf – music comes from your guts.

"From

can to can't", that's how the young Riley used to pick cotton when he was

just seven years old. From when you could in the

morning until you couldn't go on any more at sunset, attending the classes of

his teacher, Luther at his wooden

school: don't drink and don't smoke, you only have one home, and that's your

body. You won't get another one, so look after it. In the same "from can

to can't" way, B.B. King kept spreading the word of the blues throughout the world, until his body called it a day. Because his soul told him to, and because Lucille asked him for one more song…

"Lucille

just plays the blues…give me one more, babe, just one more".