The Edge, The Call of the Carillon

by Alberto D. Prieto

Mark David Chapman, freezing after

a day loitering at the Dakota, spots

Yoko arrive as she gets out of the

white limousine. Wearing a broad-brimmed black hat, hands in her pocket, she keeps

her eyes lowered, haughty and indifferent. A few steps behind, a revitalized Lennon, mulling over the melody

recently recorded in the studio, is quickly catching up to her. His appearance,

slimmed down and happy, no longer resembles the "Make Love, Not War"

visionary. He looks more like a family man returning home from work. Satisfied, a good day at office, he looks up.

I recognize that face. I signed a record for him this morning. Is he still hanging

around? What is it with these bloody fans?... Bang. Bang. Uhhhh. Bang.

It's the 8th December in New York.

The year is 1980. And Lennon had been

killed.

Adam, Larry, Bono and The Edge had already spent three days

in the city of skyscrapers and made their debut at the Ritz two days earlier. The American adventure of these young Irish

lads called U2 was starting off in

sweaty clubs with terrible acoustics, full of cheap whisky, beer, and cigarette

smoke. All four were in their early 20s. With an album already under their arm,

they were starting their attempted colonization of the New World, a task that

from that point on they took as the key to bringing their message to the world.

That day would still be a few

years away and the next morning, obviously, the newspapers didn't dedicate a

single line to them. They spit out the terrible news for a few cents an issue:

there already were no news vendors there, only cold machines frozen in the

bitter New York winter that you could buy a copy from. Lennon had died, punk

was flagging and that's where we stand, guys.

The geology of rock left its

Jurassic period behind then once and for all.

It is the 9th December 1980, still

a month before Island Records has

scheduled the release of the ‘Boy’

album in America. Nevertheless, the Irish quartet had already taken the plane

over, inspired by the enthusiastic response generated on WBCN, a small local

radio station in Boston, where ‘A Day Without Me’ was burning up the

phone request lines. The magazines following import records, the small record

stores specializing in non-mainstream discs, a sharp DJ on the lookout for new

talents and the watchful eye of their manager, Paul McGuinness, brought about the miracle. That and the truth that

the stylus revealed in the grooves of their LP. Each track is a potential

single, everything is in the right place.

In contrast to what was defeating pompous '70s rock, that punk amalgam of screams, defiance and

superimposed noises for spitting on an audience that was guilty for being

the consumer; facing that contradiction

of stars born from alienation now turned into gods in the eyes of their fans,

with the dichotomy of having given shape to an anti-system system, an

anti-business business, against all that, we say, this band of Catholic

musicians wrote each song as a meaningful piece, and each member put their

still-developing skills at the service of the message.

Lyrics, vocal performance,

percussion, the rhythm of the bass and guitars (so many already, so many even

then), took their proper space as dictated by the song. On those first gigs and

recordings, The Edge was already unveiling

an arsenal of stilettos, echoes, delays, tones, solos and

riffs. The brilliant sound of the LP is apparent

from the first spin around the turntable, the alter ego to Bono's tremendous versatility in front of the mike.

Does one of their secrets to

success for over three decades in the business lie there? In their first

interviews during the early '80s, The Edge (born David Evans on the 8th August, 1961 in London, England) related

that his main intention was to talk to audience members after each performance.

“It's okay that we have a certain

prominence with respect to them in one aspect of art, but we're just the same

as them in everything else. We're people. I'm really interested in what the

people who pay to see us think and talk to them”.

Today access to the biggest band

on the music scene is an impossible notion. But the four of them continue to go

out for drinks when they're on tour. Together. As a group. Like friends from

school. With all their ailments, baldness, overweight, they are a band of

friends. And in the current songs, just like the old ones, and the ones to

come, there is always a place for hearing and appreciating the instrumental

contribution of each member.

Although let's not fool ourselves

here. The U2 sound are the words

sung by Bono and the carillon

ringing from the pick of The Edge,

who achieves levels of virtuosity playing live very close to those he reaches

in the studio. It's a responsibility shared by both of them, from the innate

leadership of one —”Bono wasn't the best

singer… but he had that certain 'something' and that was what I was looking for

when I put the notice up on the school bulletin board ”, Larry once said-- and the other's

ability to create atmosphere and ambiance. To create and then tele transport

them to the stage is an effort that certainly requires having selected every element

in the mix very well. And so we return to that ever so intangible thing that is

the song as a complete work.

Sound and message. To be in your

20s during the early '80s was to live in an unrelenting grey, gloomy winter, a

climate inherited from the previous generation, full of spies, distrust and

opposing factions. In Ireland, the blocks were also made of cement and flew

through the air towards the heads of the residents of the neighbourhood next

door. They responded with gunshots that made bloody Sundays useless for praying

to the same God. Protestants and protests, tear gas and absurd tears with no

winners in sight and losers with names and surnames. U2

gave voice to all that. And translated to music militant messages of being fed

up with it and hope. Message and sound.

A scholar of the electric guitar can identify any of the

greats on first listen. But only a handful of guitarists are recognizable to the general public. One of them is The Edge, this Irishman born in London

with shy gestures, a nasal voice and eyes that light up in front of a guitar.

Placing his skills at the service of the collective group sound in every song

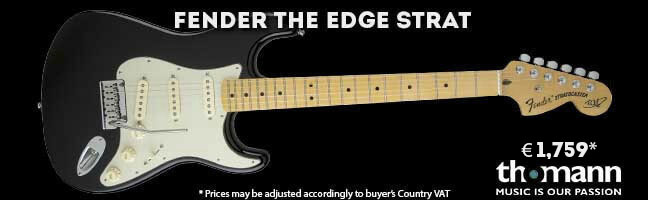

hasn't prevented him from developing his own musical personality. Playing scales on however many Gibsons have known his fingertips, all

the Fenders he's slung over his

shoulder, every Rickenbacker or Gretsch he's been able to hold in his

hands, having mastered his skill in handling the tone controls, volume and tremolo,

a collection of countless foot pedals,

cables and distortion effects, playing in so many registers, always loyal to

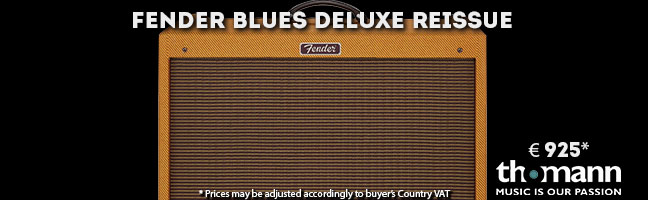

the same amplifier, a Vox AC-30 Top

Booster from 64 with the speakers patched up and chipped after being

knocked around so much, he has never deviated from his path. And whether dry or

with echo, clean or dirty, picked or strummed, The Edge's guitar always follows its own zigzag path.

“At first we just wanted to earn enough money for the rent and some

pints by doing cover versions but, what the hell, we were so bad we decided to

do our own material... by the time we wanted people to notice us, we had

developed our own style and it worked!”

So says the guitar virtuoso of U2, probably sinning from a false

modesty towards himself and his bandmates. They were in exactly the right spot

at the right time, in New York, the capital of the planet that marked a

changing era in the '80s, giving itself over to television and mass culture.

They would harvest the seeds sown on that brief tour years later; a reign over

the pop-rock world that spans three

long decades now after burying punk,

survived the New Romantics and aided

the growing decrepitude of heavy metal,

viewed the birth, glory and fleeting triumph of grunge and witnessed the evolution of rap in hip-hop and R&B…

It is the 9th March 1987, and

millions of copies of ‘The Joshua Tree’

fill record stores all over the planet. U2

plants its white flag everywhere the band sets foot.

The guitars of the quiet guy on

the corner of the stage are the ones that dressed up the rebellious melodies

and defiant challenges of the early days and then equipped them for the Irish

quartet's world conquest. And following his lead, Clayton, Mullen and Bono took the plunge into the

unexplored space of electronic pop, with that expert producer of

Berlin trilogies Brian Eno on the

other side of the mixing board --in this case, the results were ‘Achtung Baby’ (1991), ‘Zooropa’ (1993), and ‘Pop’ (1997). And those picks were the

ones that sketched out the soundtrack of the ‘road movie’ they starred in

during the 2000s, supporting the song writing stumbles with forceful,

effects-laden riffs during an uneven

period punctuated with ups and downs.

Finally, the strings and frets

underneath his fingers found their peace again when the four friends went back

to their old neighbourhood and breathed the same air as the early '80s, on the

same streets wet from dark beer, political graffiti and running ahead of the

smoke bombs and rubber bullets.

The Edge also doesn't give much

importance to the sonic support he gave the band during that whole journey.

This is how he explains the secret of his characteristic tone, based on

repetition of the same note with two different strings chosen from among the

four highest ones.

“I was intrigued by playing that game of trying to make my instruments

sound like a 12-string. Like a smooth ring-ring. I do chords that way just from

my own personal taste... and look, suddenly one day, I discovered I had

developed an individual sound that was me with a guitar on my shoulder".

The Edge has always demonstrated a

keen interest in investigating and exploring in depth the different avenues of

digital technology to increase his knowledge and further refine his

instrumental performance. Curiously, his sound never suffers or stops being

recognizable. "Notes come at a cost

for me, it’s all about quality over quantity. I'm more interested in what I can

do with them than how many I can play”.

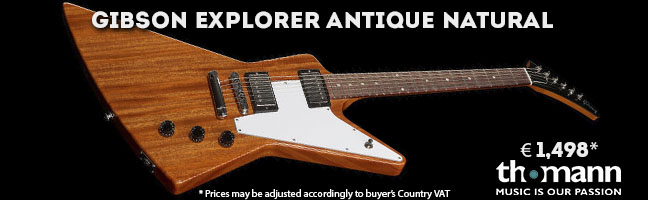

The sonic minimalism of his tone

is a product of the little value that Evans

had for the dirty sound of the fifth and sixth strings on his vintage Gibson Explorer. Despite his growing

collection, this instrument was his main guitar almost exclusively on the first

album ('Boy’, 1980) and up through

the halfway point of the sessions for the second ('October’, 1981). Today, he can bring around 50 different guitars

with him on tour. And all so he can use 15 to 20 different guitars plugged into

a dozen amps during each show. “I always

want more, to invent new things, not just go along with the flow, and try to

find the most appropriate sound for what I want to give to every song”.

That Explorer just happened to have been bought in New York, on a trip The Edge took to New York with his

parents when he was a teenager. He was still only Dave then, a kid with a sharp nose and a twinkle in his eyes, the

younger brother of Dick, who he

competed with on guitar and piano at home. That used guitar cost his parents

$450 in 1970s dollars, a good deal of money in those days, “but the instrument was worth it. I loved it

from the moment I picked it up, with those high notes…” That guitar, a '76

reissue of the original '58 Explorer,

was The Edge's companion in the

first stages of the group when, using the names of Feedback and The Hype,

they all got together in Larry's

kitchen to make up choruses and bang away at verses.

It was an absolute coincidence

they got together. It wasn't only that they got along so well after responding

to the note Mullen put on the

bulletin board at school. They also

shared common interests, the same religious sentiments, were all about the same

age with personalities that complemented one another. All that helped for each

one to take on their role and that Bono's

lyrics and melodies, woven into the rhythm mastery of Mullen and Clayton,

would be dramatically cloaked in the ethereal costumes of The Edge.

That and the four Irishmen would

try to set up their sonic carillon in the right place, the centre of the world.

And what they did at the right time, when the crater opened by Chapman's bullets killing the old

Messiah opened the way to a new era. They rang the bell of a new generation fed

up with the cold wars of their elders and eager to channel their rebelliousness

into something positive. And the people came to the plaza.