Gary Lucas Exclusive Interview

By Paul Rigg

“The guitarist who plays like Dali paints”

At a moment in history when Nasa is flying the first helicopter on another planet and returning rock samples from the primordial asteroid Bennu, Gary Lucas is appropriately releasing an anthology of his extraordinary other-worldly work. The double album provides an overview of over four decades of musical innovation with iconic artists such as Captain Beefheart, Jeff Buckley and his own band Gods and Monsters.

But this collection, The Essential Gary Lucas, released on 29 January 2021, offers far more because it also contains less well-known gems from, for example, his explorations into Cuban, Hungarian folk and 1930s Chinese music, including a Mandarin cover of Bob Dylan's All Along the Watchtower. Is this starting to feel like someone has dropped something mildly hallucinogenic in your coffee? If it does then you will also understand why the New York Times described Lucas as ‘the guitarist who plays like Salvador Dali paints.’

In this exclusive interview with Guitars Exchange Lucas reflects on his storied career, the future of the guitar in music, and how Dylan’s team reacted to that Mandarin cover version...

It is mid-May 2021, and the weather in New York is cold and blustery. Lucas has just got back from buying bagels for breakfast, and he is suffering with hayfever, but he is generously in the mood to share facts and anecdotes from his varied and adventure-filled musical odyssey:

GE: What excited you most about curating ‘The Essential Gary Lucas’?

GL: I just thought that 40 years is a good marker to remind people of what I’ve done. I’ve put out so many albums and released so much material over the years that I found myself lost in the middle of it all, and if I am lost then how is the consumer going to feel? Somebody I think had to curate the highlights and who better than me, because I know it pretty well…

The goal was to pack two cds full- and as a cd can hold 80 minutes that gave us 160 - and to include often unheard material from Gods and Monsters and other rarities, and that led to there being two main rubrics. People had different ideas on how it could be done, for example chronologically or splitting it into acoustic and electric, or putting out multiple vinyls, like in a 5 or 6 album box, but that didn’t seem realistic. Anyway, if people get excited about it, I will have done my job.

GE: I’d like to ask you about a few of my favourites, firstly from the Gods and Monsters songs on disk 1: Evangaline and Lady of Shalott reminded me of some of the renaissance music that Ritchie Blackmore now does with Blackmore’s Night; is there a link?

GL: I hear what you are saying. I am a fan of Ritchie but basically I love the aggressive Deep Purple songs from my youth. But really I was a big fan of English folk, Pentangle, and Richard Thompson, and I am playing it on acoustic, so that is how it came about.

Lady of Shalott arose because an English guy who’d lived in America for years called David Dalton, who had written rock biographies and is a good friend of Marianne Faithfull, came to me with a poem that he thought might interest her. So this is one of the few times I wrote ‘from the lyrics backwards’ because normally I write the music, hand it to a singer and say put your lyrics on this. I had to change a few things but essentially I thought I did a faithfull rendering as it had this kind of ‘Elizabethan guitar mode’ or whatever you want to call it, but Marianne passed on it. Anyhow, I felt it was a good song, so I adapted the pronouns on it, and thought it was a keeper when I put this album together.

GE: For me ‘Skin Diving’ is a fantastic song because of its driving and catchy riffs, mysterious vocals and varied elements; could you tell us about its development?

GL: Like most of these things they begin as solo guitar instrumentals. I pass my finger over the strings, often in open tunings, and I find something that sounds cool and I get a tape if it sounds evocative. Then gradually over a day or two, like a sculptor making a form out of a block of marble, I write new parts so it eventually sounds right to me. If I sleep on it and can remember it the next morning then I think I have a keeper. So it has got to work as a discrete instrumental piece and at that point I think ‘whose voice can I imagine on this?’

That track with Elli Medeiros came about because she was in town from her home in Montevideo, Uruguay, and she nailed a beautiful sensual vocal on it in French. I often think that I’m trying to give a listener an orgasm with my music - with #Metoo I am holding back a little bit on that description; but isn’t that the function of music, to move you?… I like fireworks!

GE: ‘Grace’, which you did with Jeff Buckley, is full of unexpected twists and turns in both the music and the vocals; in this sense did you and Jeff surprise each other?

GL: Absolutely. To give context a friend had called me in Spring ’91 and said ‘I want to do a tribute to Tim Buckley’ and I said ‘I love Tim’; I used to play him on my college radio show. At that point I was with Colombia Records, so we went to rehearse this Buckley song two days before the concert and my friend mentioned Jeff, Tim’s son, and said that we should think about doing something together. So I first met Jeff after that rehearsal -he had like sparks shooting out of his eyes - and he said ‘I love what you do with Captain Beefheart,’ and I said ‘why don’t you come round tomorrow and we’ll work out an arrangement of The King’s Chain?’ So I prepared some looping, pretty psychedelic, and Jeff came over and I handed him my mic and as soon as he started singing I’m like ‘Oh my God!’ I couldn’t believe the voice coming out of this skinny little kid - he sounded like a choir boy crossed with an old blues man - I couldn’t believe what I was hearing! When we finished I said ‘Jeff, you’re a fucking star’ and he said ‘Really?’ He had some insecurities - some people were like ‘you suck, the only reason anyone likes you is because of your father’. So the show ended, it went well, and he went back to LA; we parted in a friendly way. I did a tour and then had a disagreement with my record company who pulled the plug on an album deal, but I remembered I had Jeff in the wings and he said ‘I’ll be your singer’, so I went to bed happy.

We had one song that was basically a jam that we’d written on the day we met. So I needed to write from scratch and over a week I got the two instrumentals that became Mojo Pin and Grace, and sent it to Jeff. The one that became Grace was entitled Rise Up To Be – pretty much to encourage Jeff with the idea of ‘let’s get this band going’– and he said he thought they were beautiful and said ‘I’m coming to New York in a month’. So he showed up and said ‘you know the song you called Rise Up To Be, now it is called Grace.’

A couple of days later we went into the recording studio and when he finished the vocals he said ‘was that any good?’ and I said ‘you’ve just knocked it out of the park, buddy, that was unbelievable!’ There was a jazz musician arriving for the next session, and they did a playback as the guy showed up, and I observed his face looking like ‘what the fuck is this?’ And I thought ‘this is going to rock the world man!’

Jeff and I loved the Doors, The Smiths and Led Zeppelin, and this was trying to update the idea of a guitar hero and a rock god singer. We were offered 20 thousand by a record company to finish the album but Jeff didn’t want to sign the deal and I didn’t understand what was going on. It turned out he had found himself a lawyer/manager. We did a show in April and there was an A&R guy there from Colombia saying ‘hi Jeff!’ and I thought ‘oh no, man...he wanted to go with Colombia’! This is the cross I have to bear, even though he’s been dead a long time, I’ve made my peace with it …

GE: What is the story behind the lyric?

GL: The lyrics I never asked him too much about, but Grace seems to be about a guy who is having very miserable thoughts [about ending it all], but he has a woman he has idealised, so he resolves to ‘wait in the fire’; it is a romantic agony in 19th century Victorian novel mode. Once I asked Jeff what Mojo Pin was about and he mimed shooting up and I thought ‘well if that’s what he wants to sing about, I like the Velvet Underground, I’m not a user but I’m a libertarian…’

Those songs have a resonance with young people, particularly young women, because Jeff’s voice is so strong and sensitive and he’s talking about intimate moments with lovers. Plenty of people didn’t get it in this country… I had a friend who said they were watching MTV with a group of male rock fans and when Grace came on a shower of beer cans were thrown at the TV [laughs]… but I think they are effective because both songs go from major to minor and I think that mirrors a little bit the bitter sweet quality of life…

GE: Disk 2 kicks off with ‘All Along the Watchtower’ sung in Mandarin; how did that come about?

GL: I have spent about 25 years doing Chinese music of various modes. I spent a couple of years of my youth in Taiwan where Mandarin is spoken, I didn’t learn much of the language but I love the music. The scales and the things that most westerners think is a noisy racket, I love - even the 70s corny pop songs. I had a girlfriend there who was very intelligent and sophisticated and she put a tape on for me. At that time Shanghai had a thriving film studio and a whole number of pop-idol type men and women who were groomed for the stage, and this music combined east and west in a beautiful way, with the scales, the jazzy broadway tinpan alley swing, and orchestration with Chinese, Europeans and war refugees… so I fell in love with this music and turned Beefheart on to it, and then I started to do arrangements of these songs and putting them out on albums. Anyway, I met vocalist Feifei Yang and said I’m looking for a singer for All Along The Watchtower. A friend then said ‘why don’t you do a whole album of western pop classics in Mandarin with some Dylan, Simon and Garfunkel and Leonard Cohen?’, so we did a record, which is in the can, and we are now looking for a release date…

At the moment we are getting a very heavy wave of anti-Asian prejudice manifesting in the US as a result of the virus, which Trump took great effort to blame on the Chinese. Who knows what its origin is, but do I think they deliberately created it? – no I don’t. So I am hoping that this will convince my backers to put this album out here. They have suggested putting it out in China first but it seems to me most young Chinese people are into artists like Billie Eilish and Lady Gaga – and I don’t know how this would fit in their wheelhouse! I think it is much more for European world music fans.

GE: Do you know if Bob Dylan has heard it?

GL: I know Bob Dylan’s manager really likes it. I don’t know about Bob, he never comments on his covers, famously. I have an English friend who did a version of It’s Alright Ma and he was dying to get a quote from Bob on a video and I said ‘you’re dreaming- even if he knew you he’s not going to do that!’ He’s in his own space, it’s like when he won the Nobel prize, he didn’t respond for two weeks because he said ‘I’ve been busy with some things…’ [Laughs].

I think though the video of it was very original because I got many historic photos and engravings of the Great Wall, and it fits, because people asked ‘how do you walk along a watchtower?’ well, guess what, the Great Wall had a parapet and [guards] looking for enemies!

GE: There are several acoustic instrumental numbers on the second disk - Janaceck’s ‘On an Overgrown Path’, Will o’ the Wisp, Flavour Bud Living – how, for example, did the latter come about?

GL: Well that one does sound acoustic but I actually play it on a Stratocaster. Captain Beefheart wrote it and he always maintained that a guitar is basically a stand up piano. He used to improvise pieces with both of his hands in a technique that is known as ‘through composing.’ And he handed me a tape once and said ‘learn this’, and I said ‘you need 10 fingers to do that but there’s only six strings on this thing’ and he said ‘well you better find another four, man.’ He’d goad you to try and find a means to do it, which I did do with my arrangement. I noticed the lowest note was a D on the piano so I put my E string down to D. It was lucky because the tonal centre was mainly low D, although it wanders out of key in places… anyway, I learned it and played it and he said ‘yeh, that’s really good, but it’s not the whole thing’ and I said ‘what do you mean?’ and he said ‘I’m gonna send you another tape, just tack that on to it’ so I got the second tape and I joined them up.

GE: You play with Nona Hendryx and Jerry Harrison on this album, both of whom were key in Talking Heads; is there a strong link with the whole band for you?

GL: Yeh, I like David [Byrne], he is a friend, though I don’t see him much. He came backstage when Gods and Monsters played with Plastic People, the Czech underground band, some years ago, mainly to meet Vaclav Havel [the former President] who we knew was coming because of Lou Reed. Jerry Harrison was at that point playing with us and Jerry suggested Nona because she had been on The Remain in Light tour. I can’t really afford Jerry these days … but he’s a good guy.

GE: Your collaborations on this album include, for example, Television’s Billy Ficca and New York Dolls’ David Johansen; do you have a particular fond memory when I mention those names now?

GL: Well, yeh, [Laughs] Billy is a bit of a space case, insofar as he loves his drink. You have to make sure he lays off the booze before a show. We had this gig in the Austrian Alps, quite close to Hitler’s mountain house, and originally they wanted Jerry to do it - that’s how we got the gig – but I didn’t have the budget, I cannot run my band at a deficit, I just can’t, so anyway, at the time we were supposed to assemble to do the soundcheck there was no sign of Billy. He had wandered up into the wild blue yonder. So they sent a search party out for him and they found a little town and walked into a boozer and there he was! He said ‘where have you guys been?’ And we were like ‘but you were sure we were going to turn up?’ and he replied ‘well, I was out there, and it started to rain…’ I love him.

David I’ve known for years because I worked with him as a copywriter on his first solo album and we stay in touch. Once he was playing with the Dolls and he invited me to take a road trip with him up to Ithaca, New York, when Joan Jett was opening for him in the days before her big hits. He did the best show and a reporter came up to him afterwards and asked ‘how do you find it up here, Mr Johansen?’ and he replied ‘Bucolic!’ [Laughs]. He’s so funny. He had a whole pile of funny hats and when they did their last song, Personality Crisis, he kept putting a different hat on. I love him, he’s one of the greats… Martin Scorcese is doing a film and I’m sure The Dolls will be in it…

GE: Going back to the start of your career, at what age did you start to play guitar and what brands have you liked?

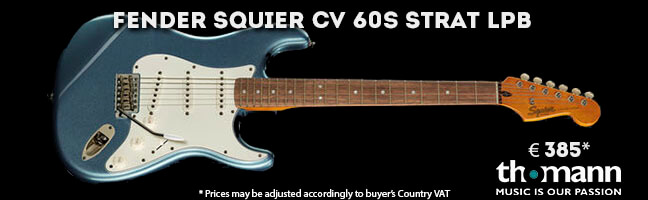

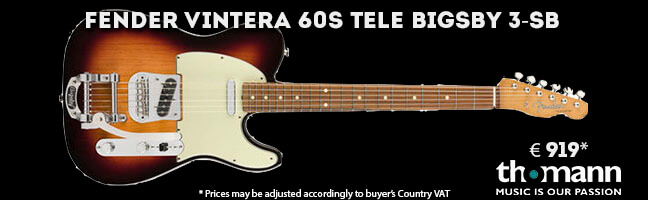

GL: I started playing at around nine years old, on my father’s instigation. He rented a real cheap-ass horrible instrument, strings way off the fretboard, a Kay I think, and I thought ‘I’d rather play football with my friends!’ [Laughs]. If it wasn’t for the fact that my parents took a trip to Spain and returned with a beautiful Spanish guitar, I never would have made progress. So I started playing a lot of pop folk music and then rock before the British invasion hit. At 13 Dad got me a Stratocaster for my Bar mitzvah but I couldn’t get a good tone out of it, so foolishly I sold it and replaced it with a Swedish Klira. Eventually I got an Epiphone Coronet with one pick up and got some good sounds out of it. Later I joined the Yale Marching Band - we did stuff like the Theme from Shaft - and as I was leaving some guy sold me a ’64 Strat for 200 bucks, it probably was hot. I lost that one in the luggage on a train, it’s a sad story, and on the insurance I got a ’66 replacement. I don’t have a lot of guitars, I have this National Steel from the 20’s that I played with Beefheart on Skeleton Makes Good for example, I have a Firebird, a Mexican Strat, an old Tele, that’s about it. I prefer vintage instruments; anything that’s too new and shiny doesn’t interest me at all…

GE: Your first big impetus in music was with the great Don Van Fliet, better known as Captain Beefheart; you started as a fan, then friend, co-manager, and ended up playing on his last two albums. At the start, did you ‘put yourself forward’ or was he the one who decided he wanted you to play?

GL: I put myself forward, but it took a while. When I met him I just wanted to get the message out to people what a genius he was; I was so impressed. I was shy and didn’t think I’d be up to playing his music, but secretly I started learning it off his records. At that time he was involved in the period fans call ‘The Tragic Band’, and I saw he was going to play with Zappa so I went to see him. He recognised me and we went to get some barbeque ribs… and in the middle of this I said ‘if you are putting a new Magic Band together let me know’ and he said ‘you play guitar?’ So I played for him and he said ‘great!’ Later I arrived with my new Chinese bride in ‘77 and called him and saw him play, and then in 1980 he sent me Flavour Bud and that’s how it started.

GE: By the time of ‘Ice Cream for Crow’ you were fully integrated in the band; what is your favourite memory of that recording? I guess you’ve been asked that before…

GL: [Laughs] Yeh ... at ‘Frank and Don Please kill me.com’ you can read a whole bunch of funny stories. [Silence] Okay I’ll choose one. One of the records he gave us to learn was Semi-multi coloured Caucasian, which was a jaunty piece, and we played it in a rehearsal. We thought it was fun but Don turned up and said ‘what are you doing fucking about with my music, it’s not like that!’ [Laughs]. He was like that, very capricious.

Then he said ‘everyone likes a fake ending where the vibe starts to end and it then surges back, but I’m going to put a fake beginning on this.’ Like this [mouths the riff] … people will think the needle is stuck in the groove and they will have to check it, so we learned it that way. Then later he said ‘what are you doing ruining my song man, put it back, forget what I told you!’ So we got rid of the false beginning.

GE: What guitar did you use on that track?

GL: My 64 Strat, the same I used on Grace.

GE: I have a few general questions to finish. The first is, The New York Times once said that you play like Dali paints – how did you respond to that description?

GL: I accept that. His imagination ran everywhere; some of his paintings are fantastic. Like Dali I think I have a very solid technique, which was stretched by Van Fliet, for example, when I had to do big stretches with my hand to do intervals that might not occur to most players. I like it, I thought it was a good description.

GE: Are there any modern artists who particularly move you?

GL: Adele and Amy Winehouse captivate me. Lhasa as well, when I first heard her, she had just died the previous year and I thought ‘damn, I’ll never see her’, but her album The Living Road is so good… she has such a beautiful voice. Joanna Newsom has a spectacular voice and is a beautiful, mystical, songwriter. I am more partial to female artists, but I often miss them when they are in New York… it is my fault because I don’t keep up with modern music.

GE: You have played across many music genres, with the common nexus being the guitar; but does it have a future?

GL: I am sure it does, more and more people play it, it is so universal. I like it because it is like having a little orchestra in your hands, you can achieve complex harmonies and play it with different tunings. So it’s not going away. As a primary instrument in some ways it is a cliché, which is why I try to avoid playing standard guitar.

GE: What plans do you have for this year?

GL: I am trying to get back on stages. I have just got this gig in September. If someone books me in the summer that would make sense. As far as getting to Europe is concerned, it is difficult at the moment. I like to travel. I’m dying to go back to Spain.

The interview closes with Lucas asking about several specific restaurants he loves in Madrid, where I live, and asking if they are still open. He mentions a popular calamares bar, for example, near Plaza Mayor, and he says he often remembers cities by the food. Then he fondly recalls a concert he did in the city, and his time in the Prado Art Museum looking at Goya’s ‘Black Paintings’. “I love Madrid,” he says, “It is a great city!”