Keith Richards’ 10 Best Riffs

By Sergio Ariza

Keith Richards is the heart of the Rolling Stones and, besides being the architect of their sound, defined by some of the best riffs in history. If in other bands one follows the drummer - in the Stones, according to Charlie Watts and Ronnie Wood, one follows the guitar of Keith Richards. ‘Keef’ has always placed a well executed riff before a long solo, and created his own style while he does it. This is thanks to his special tunings and how the riff is adapted - and how he has adapted, and along with him the band, to them. These 10 riffs form a part of the history of rock & roll.

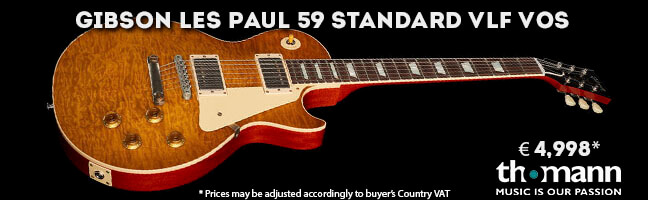

(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction (1965)

Three

fucking notes. That is all that Keith Richards needed to make himself immortal.

The riff of Satisfaction is a

monument to the marvellous simplicity of rock & roll, to how one can start

a revolution - with something so simple and, at the same time, fantastic - with

three notes played with a Les Paul Standard 59. The incredible thing is that

these notes appeared to Keith Richards in a dream. The ‘riff master’ has always

said that the most legendary of all riffs came to him one morning as he woke,

with an acoustic in his arms and a tape-recorder at his feet. Keith rewound the

tape and at the start he found this mythical riff recorded ... followed by half

an hour of snoring. He didn’t remember recording it but he finished the song

and passed it to Mick Jagger to add

the iconic lyrics. Then the notes were converted into electricity, the Stones

became legends, and the Les Paul into the guitar to have.

Citadel

(1967)

I have allowed myself to include this small

hidden gem for various reasons: to highlight the Stones’ enormous catalogue

beyond their classics but also how this song from their controversial

psychedelic period serves as notice of the sound that would define the Stones in

their moment of glory, that of 1968 to 1972. Constructed on a great riff of

chords by Keith (in the style of Get Off

Of My Cloud), Citadel is a lost

classic which should be offered the opportunity to appear in its current highly

selective setlists.

Jumpin’

Jack Flash (1968)

When you are the favourite riff of Keef

himself, you are not just any riff. Richards has always been particularly proud

of the riffs of Jumpin’ Jack Flash

and Street Fighting Man, two of the

great classics of the band for which he didn’t even use one electric guitar. It

could be that the former is one of the most iconic given that this is the song

that opens the period of their splendor, the one that goes from Beggar's Banquet to Exile On Main Street. In order to achieve that sound Keith played

his acoustic Gibson Hummingbird with tuning in open D and a capo in E, as well

as a second acoustic guitar that provides the opening chord; and this in a ‘Nashville

tuning' in which the four last strings are replaced by thinner strings tuned an

octave higher than normal. To this can be added the fact that all the guitars

are recorded through a cassette recorder that gives it that peculiar sound,

near to electric, which inaugarates the triumphant phase of the Stones. On top

of that, Keith also took responsibility for playing the iconic bass part on the

song. Since that time nothing represents the sound of the band better than this

song.

Gimme

Shelter (1969)

The recording of Let It Bleed was one of the most important, and complicated, in the

history of the band. This was at the time when Brian Jones was fired and then, a month later, found dead at his

mansion. This also represented the first appearance of Mick Taylor on a Stones’ record, one that put the soundtrack to the

turbulent year of 1969. Keith Richards played almost all the guitars on the

album - because of Jones ‘lack of presence’ and the late appearance of Taylor -

but it was from another guitarist that he would learn the tuning that would

become his ‘trademark’ sound and became the heart of the 'Stone sound' for the

rest of their existence. It was Ry Cooder who participated in the

sessions for Let It Bleed, although

in the end he only appears playing the mandolin on Love In Vain. But during the recording he was jamming with the rest

of the band, as can be heard on the album Jamming

With Edward, which the Stones themselves released in 1972. It is on this

album that Cooder uses his familiar open tuning for slide that Richards would

convert into the foundation of his rhythmic style. One of the first examples

was on Gimme Shelter, whose

well-known riff at the start is one of the best of his career. For this

recording Richards used a Maton Supreme Electric 777 that someone had left at

his home so that he would ‘take care of it’. Richards took it to the recording

of Let It Bleed and used it to record

two of their most remembered songs, Midnight

Rambler and Gimme Shelter. On the

final note of this last song the neck was left in pieces. But by that time the

guitar had aready found its place in the history of rock.

Honky

Tonk Women (1969)

Keith Richards has always said how Honky Tonk Women was created in Brazil, during

some ‘coupledom’ holidays that Richards and Mick Jagger took with their respective

partners of that time (and members of honour of the band) Anita Pallenberg and Marianne

Faithfull. They stayed on a horse ranch and they were playing at being

cowboys when Keith started to play a song that was pure country. That is how Country Honk, emerged, that would form a

part of Let It Bleed, but, once

recorded, Keith and Charlie Watts started to fool around with it during a

rehearsal with a rhythm and a riff. Richards continued playing with his new

open tuning in G, learned from Ry Cooder (copied according to the author of Paris Texas), and this riff came out;

Watts started to follow him and that is how another of the band’s classics

emerged (it is unclear if he played it with a Telecaster or a Les Paul Jr.). It

was also one of Mick Taylor’s first recordings as a new member of the band. On

the day that he finished recording, on the 8th June 1969, Richards, Jagger and

Watts drove to Brian Jones’ house to tell him he was fired. In another macabre

coincidence, the song was released on exactly the same day that they found

Jones dead in his swimming pool, on the 3rd July 1969. There is no better proof

that the band was entering a new period. Goodbye to the 60s and welcome to the

70s.

Brown

Sugar (1971)

Sticky

fingers is strictly speaking Mick Taylor’s first album

with the band, and his presence can be felt. The sound is electrified and

distorted, besides serving as stimulus for the creation of some of Richards’

best riffs, like those of Brown Sugar,

Can´t you hear me knocking and Bitch,

three great ‘hard rock’ songs that would define the sound of the band for the

rest of their career. The first is the best known, one of the most remembered

of their career, and the one which has most been chosen to open their live

performances. The song was recorded in December 1969 in the mythical Muscle

Shoals studios, a few days before the infamous Altamont gig, in which it would

have its live baptism of fire. They recorded it again on 18th September 1970,

with Eric Clapton on slide guitar, but

everyone agrees that the version from Muscle Shoals was better and this was the

version finally released in 1971.

Can’t

You Hear Me Knocking (1971)

It could be that Brown Sugar is more popular, but Can’t You Hear Me Knocking is my favourite riff by Keith Richards.

Newly employing his beloved open G tuning, Richards skillfully plays a riff that

becomes a master course in rhythm guitar. In his own words: "on that song, my fingers landed in the right

place and I learned various things about that tuning that I had not realized

before”. To complete the song there is a magnificent jam with a great solo

by Bobby Keys on sax and Mick Taylor

on the guitar, with various nods to Carlos Santana.

Bitch

(1971)

For the third riff that comes from Sticky Fingers, Richards uses another of

his iconic guitars, his Dan Armstrong Plexiglass. The story about how this song

became another of the band’s classics is told by Andy Johns, the sound engineer: "we were doing Bitch, and Keith was late. Jagger and Mick Taylor were

playing the song without him and it didn’t sound very good. I walked out of the

kitchen and he was sitting on the floor with no shoes, eating a bowl of cereal.

Suddenly he said, Oi, Andy! Give me that guitar. I handed him his clear Dan

Armstrong Plexiglass guitar, he put it on, kicked the song up in tempo, and

just put the vibe right on it. Instantly, it went from being this laconic mess

into a real groove. And I thought, Wow. THAT'S what he does.”. No-one could

sum up better what it means to be the man who put the ‘Stone sound' into the

Stones. By the way, once he’d done that, he also had time to deliver one of his

best solos.

Rocks

Off (1972)

If an alien came down to earth and asked ‘what is rock n roll?’ there would be

no better response than putting on (at full volume) Exile on main street. After listening to the riff of Rocks off the alien would already have

quite a good idea, but listening to it closely, he would know the creature is a

bastard with many fathers, blues, country, gospel, folk... All of them fit

comfortably at the peak of the Stones career of which this song is the perfect

presentation. As could not be in any other way, it was during these sessions

where Keith began to use the guitar with which he is most associated, his 53 Fender

Telecaster that he called Micawber in

tribute to a character from the novel by Charles

Dickens.

Start

Me Up (1981)

Start Me

Up is the last great classic of the band - and it was

at the point of not being so. They recorded it during the sessions of Some Girls, and it was based on another

great riff by Keith. The rest of the song was by Jagger, but after a couple of

takes, Keith thought that the riff, again with his open G tuning, was too

similar to Brown Sugar and the song

became a reggae number, one of Keith’s big influences during the 70s, which in

the end was rejected. Three years later they were searching to find more

material for the Tattoo You album and

the producer Chris Kimsey remembered

the song. When they listened to the first take, with the great riff, they

couldn’t believe they hadn’t used it, so it had a second chance and became

another of those songs that could never be missed in one of their concerts.